THE BEST educators are those who encourage their students to question what they are told and think for themselves. Among composers you can always spot these teachers because their pupils exhibit few if any of their stylistic ticks. Olivier Messiaen (1908–92) is a good example, the more remarkable really because his own music was so distinctive yet he seems never to have passed his style on to the long list of composers who studied with him. What he did pass on, to some of them at least, was his attitude to teaching. Here is one of those pupils, Alexander Goehr, on the subject of having his own composition students:

My job, in so far as I function as a teacher, is to try to make students more themselves, not less themselves… After all, to be someone’s teacher is a form of service. They pay for goods rendered, and if you can’t deliver the goods you have to say so. Teaching composition is not a form of political activity; you’re not trying to convert people.

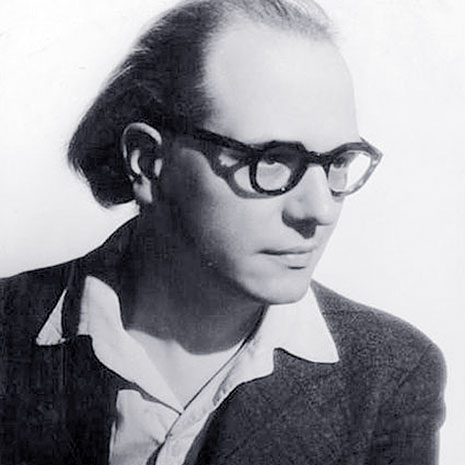

Goehr, now in his eighties, studied with Messiaen in Paris in 1956 and 1957, but the Frenchman was active as a teacher of harmony, analysis and composition for more than three decades from the 1940s until 1978, some of his more prominent students including Pierre Boulez, Jean Barraqué, Iannis Xenakis, György Kurtág, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Quincy Jones, Lalo Schifrin, Mikis Theodorakis, Gérard Grisey and George Benjamin. No teacher who produces both Stockhausen and the composer of the Mission Impossible theme can be accused of insisting on a party line! Messiaen had dozens of musical offspring and, like Goehr, many of them had students themselves. By my reckoning, there are now four and possibly five generations of Messiaen’s descendants around the world, literally hundreds of composers who can trace their creative lineage back to him. I am one: Messiaen was my teacher’s teacher’s teacher.

A new CD, The Messiaen Nexus, looks only at the first generation, but still contains quite a range of musical thought and expression. The disc includes music by Boulez, one of Messiaen’s first students, and Benjamin, one of his last, though in Boulez’s case the piece is a late one – the violin solo Anthèmes from 1991 – while Benjamin’s violin sonata is a student piece from 1976, never before recorded. There are two sets of typically gnomic miniatures by Kurtág, and the disc is rounded out by two early Messiaen pieces, the recently discovered Fantaisie for violin and piano, and a solo piano piece in memory of Messiaen’s own teacher Paul Dukas. For good measure, there’s a piano solo by Dukas himself, so the disc also takes us back another generation.

Although short on masterpieces, the music on the CD played by violinist Elizabeth Sellars and pianist Kenji Fujimura is full of variety. Notwithstanding the celebrated Quatuor pour le fin du temps, chamber music was hardly Messiaen’s metier, but his first wife Claire Delbos was herself a violinist, and during the 1930s he composed two pieces for her. This Fantaisie, written in 1933, performed in 1935, and then lost until 2007, is typical enough of its composer, the music brightly coloured, energetic, intense, full of spiritual ardour, its chromatic opening theme stepping out confidently in octaves that recall the same composer’s organ work L’Ascension and the “Intermède” from the Quatuor.

But the real interest here is in hearing Messiaen’s music in the company of some of his top students. The more one listens, the more connections one hears. Boulez’s iridescent Anthèmes, dispatched with poised virtuosity by Sellars, may lack the urgent necessity of the composer’s earlier music but, though a bit aimless, it is elegant and charming, and its colours glitter. No listlessness attends the violin sonata by sixteen-year-old Benjamin. Working under the guidance of his revered maître, the boy was evidently bursting with energy and ideas, even if they feel somehow anonymous. In Ringed by the Flat Horizon, the orchestral piece he would compose four years later, we hear strong hints of the distinguished composer we know today, but for all its fierceness and febrility, and despite the persuasive case made for it by these performers, this sonata might be by any very talented youngster. Still, fascinating.

The Hungarian Kurtág’s work is so strong that I always feel it deserves to be widely known, but its enigmatic nature counts against it, as does the fact that not many of his pieces last more than a few minutes. This is music that demands of its listener the utmost concentration – almost a kind of communion – which is not to say it is always sombre. As its title suggests, Kurtág’s continuing cycle of Signs, Games and Messages ranges in tone from the profound to the playful, always in microcosm, always deeply felt, and Sellars captures that variety here in four pieces.

From Boulez’s brilliant colours, then, to the young Benjamin’s vigour to Kurtág’s spiritual intensity: Messiaen might not have passed on his style to his students, but the example he set resonated with them all. •