Nation, “an independent journal of opinion,” was published in Sydney from 1958 to 1972, each fortnightly issue a miscellany of editorial and contributed articles on politics and the economy, manners and morals and the arts. The writers include people well known already when Nation began, among them Cyril Pearl, W. Macmahon Ball and Max Harris, and others for whom Nation found a new reading public, such as Sylvia Lawson, Brian Johns and Bob Ellis. The time runs from the middle of the Menzies age to the eve of Whitlam, from the aftermath of French defeat in Indochina to the Vietnamisation of America’s and Australia’s war, from the pill to gay liberation, from the early days of the Elizabethan Theatre Trust and Richard Beynon’s The Shifting Heart to La Mama and Nimrod and David Williamson’s The Removalists.

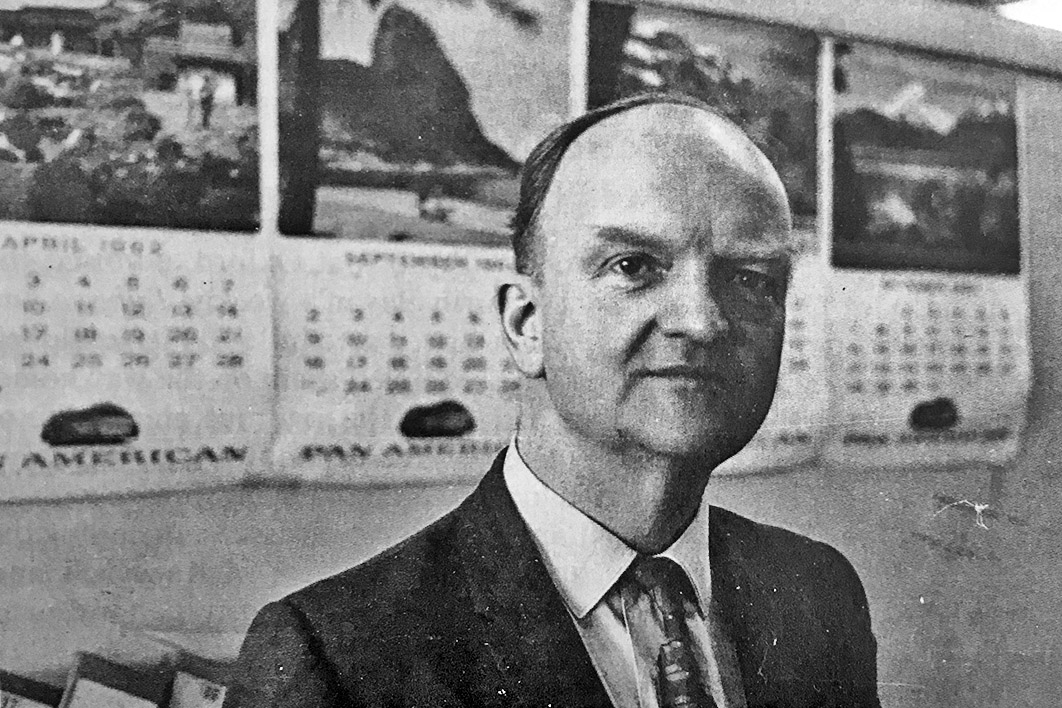

Over those fourteen years Nation readers were offered an informative, searching and quirky analysis of a nation’s experiences: the myopic foreign and opportunistic domestic policies of Menzies and his Liberal successors, the stumbling recuperation of Labor, the changing face of cities, the boom in mining shares and tax avoidance and the slide in manufacturing, the zigzag quest for cultural identity, and much else that the newspapers either dealt with partially, trivialised, missed, or — often enough to delight the journal’s makers — picked up from Nation. The principal makers, from beginning to end, were Tom Fitzgerald and George Munster.

Fitzgerald was thirty-eight, in 1956, when he decided to start his own paper. That August, Harold Levien’s independent monthly, Voice, which he admired, went silent after five years of struggle. For much of 1956 Fitzgerald was in conflict with the bosses of the Sydney Morning Herald over the limits of his freedom as “financial editor” to speak his mind in their pages. And he had lately given up a private hope, nurtured since his discovery of America on the way to war in Europe, of making a life in the United States as an economist or a journalist.

Nation once carried an advertisement for a building society showing a milkman and an aircraft officer as different types of investor. This must have entertained the editor/proprietor, for he had been both. Thomas Michael Fitzgerald was born in 1918 on his grandfather’s dairy in the Sydney working-class district of Marrickville. That grandfather and grandmother, his father’s parents, were Irish-Catholic migrants, and so was his mother. Tom was the oldest of six children. When he was about ten, health inspectors closed the dairy, but his father had become a milk vendor, helped by three of his sons on a route that took them running through old inner suburbs — Marrickville, Newtown, St Peters, Leichhardt — before dawn and returning in daylight to collect money and talk companionably with the customers. This experience contributed to a lifelong sense of identification with working people. His father had a vivid awareness of the wrongs done to Ireland but was a less frequent churchgoer than his mother.

His primary and secondary education was entirely Catholic: nuns at Tempe, Marist Brothers at Kogarah and Darlinghurst, and Christian Brothers at Lewisham. He was a devout child, acquiring in adolescence a strong reverence for the image of Jesus Christ — an attachment which he shared, as he was later to discover, with Karl Marx and Albert Einstein. From primary school he read and loved the works of Shakespeare, and was exhilarated to discover Coleridge and other English poets. He soaked up stories about cricket in Chums Annual. The wireless set carried into the family home a range of music, drama and instruction not offered at school: he learned more that he wanted to know from the ABC than from the Brothers, and envied the culture he glimpsed on visits to state schools and to the house of a Protestant aunt.

Schooled by the Brothers to believe that private enterprise was a Protestant preserve, Tom Fitzgerald joined the Commonwealth public service in 1936 and was assigned to the Defence Department at Victoria Barracks, Paddington. In the evenings he studied economics at the University of Sydney, having been awarded an exhibition exempting him from fees. He won distinctions but interrupted his studies when his mother died suddenly in 1937, and suspended them just short of a degree in 1940 when his father died and he left the Barracks to join his brothers on the milk runs. He ceased to be a practising or believing Catholic. J.M. Keynes attracted him as a writer equally at ease with technical economics, philosophy and biography, and long passages from T.S. Eliot became etched in his memory.

In 1942, knowing that after the wartime zoning of milk runs the family business could do without him, he joined the RAAF and began to train as a navigator. Waiting to embark for Canada, Pilot Officer T.M. Fitzgerald met fellow navigator Pilot Officer E.G. Whitlam, who was reading aloud to his comrades from The Faber Book of Comic Verse. Whitlam could never remember the meeting. “And if there’s anyone who hates to be outdone in memory,” says Fitzgerald with a smile, “it’s Gough Whitlam. Our relations have never been easy.”

In 547 Squadron of Coastal Command, composed of men from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, Fitzgerald flew over the English Channel before the Allies invaded France, and later patrolled as far as the Baltic. On the way to the war, spending leave in the United States, he had been excited by American society. The Liberator bombers which he navigated gave daily cause for gratitude to American industry. He wanted to salute Mr Pratt and Mr Whitney, creators of the aircraft’s engines; it was said that a Liberator could fly on any two of the four, but his pilots never had to test it on fewer than three.

He saw theatre in London, dined with dons at Oxford, and admired the spiky honesty of George Orwell in Aneurin Bevan’s weekly Tribune and Cyril Connolly’s monthly Horizon. When Orwell died in 1950 Fitzgerald felt he had lost a second father. But the United States, sampled again on the way home, attracted him more powerfully than England. The vigorous mental life of Americans, right down to the articulateness and candour of conversations heard in New York bars, exhilarated him. So did talking in Chicago with an economist of the Federal Reserve Bank about postwar issues, including the emergence of Russia as a great power. The America of Roosevelt and Truman, the New Yorker and Gershwin inspired the young Australian visitor as Churchill’s and Attlee’s England never did.

Back in Sydney in November 1945 he married Margaret Pahlow (of German and Irish ancestry), whom he had met when they both worked at the Barracks. The demobilised navigator did not relish the idea of returning to the public service or moving (as a career in the federal bureaucracy would have required) to Canberra, which always struck him as bleak by comparison with the loved landscape of boyhood. He might have gone to Canberra as a cadet diplomat, had he stayed long enough in England at the end of the war to receive an invitation that External Affairs sent to RAAF graduates there. (As a serviceman who had almost completed his course, he had been granted a degree.) Providence withheld that possibility and turned him towards journalism: while helping his brothers with the milk run he saw an advertisement in the Bulletin for a financial journalist, preferably an ex-serviceman. He applied for the job and got it.

In its seventh decade the Bulletin was no longer the bushman’s bible, or anybody else’s, except for those who believed in the slogan printed on the masthead each week: “Australia for the White Man.” Its founding genius J.F. Archibald said of the Bulletin that it was a clever youth who would become a dull old man. In fact, it had become cranky rather than boring. In Patricia Rolfe’s judicious history of the paper, Fitzgerald’s editor, John Webb, is characterised as a ratbag reactionary. He propagated xenophobia and hysterical anti-socialism. The Red Page, edited by the poet and essayist Douglas Stewart, still harboured some of the country’s best writers and was enjoyed by many people who might skip the Plain English of the politics pages for the contributed yarns of Aboriginalities, the Sporting Notions and Sundry Shows, and the financial section begun on Archibald’s initiative to attract businessmen two pages called the Wild Cat Column and two more with the droll heading “Business, Robbery, &c.,” which was both a vestige of ancient radicalism and a harbinger of Nation. Here, in his late twenties, the milkman and student of Keynes began to hone his skill for interpreting financial matters to a lay readership. He did it so well that when discomfort at Bulletin politics moved him to leave, he was offered the editorship of the associated Wild Cat Monthly at an increased salary and ran that paper until his work prompted an offer from the Sydney Morning Herald in 1950.

The mentors of his Irish-Catholic youth could never have expected to see him there, a senior journalist on the paper founded by nonconformists which had become a pillar of an Anglo-Protestant culture: if Australia had an Establishment, “Granny” Herald was right in it. From 1952, as a widening circle of readers in and out of the business district knew, the daily piece “by the Financial Editor” was Tom Fitzgerald’s. Whether on the particulars of a new share issue or company merger, or the latest balance of payments figures, or the parties’ economic strategies at election time, his editorial pieces were the work of a powerful, cultivated, clear and independent mind. He was a treasure to the Herald; insiders could not afford to ignore his expertise and outsiders read him for enlightenment and pleasure. “April is the cruellest month,” ran the heading to a piece on company troubles. “He must have been the first financial editor in Australia,” writes an admirer, “to quote T.S. Eliot.” Like the racing notes in the New Yorker, his pieces were enjoyed by people who had not known they could be interested in the subject matter.

In the feudal world constructed over more than a century by the Herald’s makers, Fitzgerald was responsible not to the editor — editors came and went, frustrated at having their authority confined to one editorial page — but to a triumvirate in offices up on the fourteenth floor: the general manager, Angus McLachlan, the managing director, Rupert Henderson, and the chairman of directors, Warwick Fairfax, great-grandson of the Herald’s founder. Relations between members of the dynasty and their most senior employees were intricate. When Vincent Fairfax, also a great-grandson, started as a cadet reporter, the general manager told him: “You might think the Fairfaxes own the Herald, but you’re wrong, because the Herald owns the Fairfaxes.”

The financial editor, as Fitzgerald saw his station, was a remote petty chieftain, conducting the financial pages as he thought best, saying what he wanted to say in editorials — so long as that was acceptable on the fourteenth floor. For Warwick Fairfax he had high respect as both a journalist and a thinker, believing that the best editorial prose of his time on the paper was written by the chairman, and enjoying serious conversations with him on and beyond economic matters. Fairfax described his association with Fitzgerald as one of the happiest he had ever had with any editorial writer.

In May 1956, however, Fitzgerald came close to resigning after the financial editor’s comments on certain economic measures lately introduced by Menzies had displeased Fairfax, whose reprimand was carried down by Henderson. As Henderson reported the exchange to Fairfax, Fitzgerald agreed that it was no part of the financial editor’s function to write comments intended to influence the prime minister. As Fitzgerald remembered it, Henderson accepted his argument that unless he was free to express his own opinions he was no use to the paper. The difference between Fitzgerald’s recollection and Henderson’s account is probably to be explained by the managing director’s need to mollify his chairman while not risking the loss of a precious asset.

A little later, in 1957, Henderson expressed his regard for Fitzgerald by proposing that he be offered the editorial chair lately vacated by John Pringle. It was occupied instead by Angus Maude. There is a legend that Fitzgerald’s disappointment at this outcome moved him to launch Nation; but Fitzgerald was not willing, and Henderson knew it, to become editor except on terms intolerable to the fourteenth floor.

By the end of 1956 he had had enough of life as petty chieftain in the Fairfax domain and worker in an industry whose quality dissatisfied him. The disappearance of Voice, a modest vehicle for some viewpoints not expressed in the newspapers, made the dullness and conservatism of the Australian press all the more vexing. Moreover, Tom and Margaret Fitzgerald were now feeling more settled in Australia. She had shared his enthusiasm for at least a spell in the United States, but their applications for visas had been lying in consular files for years, waiting to reach the top of the small quota for Australia; now they had four children, and it was easier to stay away from Eisenhower’s and McCarthy’s America than Truman’s. Fitzgerald resolved to leave the Herald and start a paper of his own.

Frank Packer, proprietor of Sydney’s other morning paper, had invited him more than once to join the Daily Telegraph, believing that as financial editor he could help the paper to improve its sales on Sydney’s well-to-do North Shore. To Packer in 1957 he took a proposal that he write as a freelance for the Telegraph while editing his own periodical. He found with surprise that Packer was also planning a journal of opinion, to appear monthly; but if Fitzgerald were to write for the Telegraph, why shouldn’t he and Packer each publish a fortnightly, coming out in alternate weeks? Fitzgerald agreed.

Back at the Fairfax building to hand in his resignation, Fitzgerald had another surprise. So highly did Rupert Henderson value the financial editor’s pen, and so confident was he of Fitzgerald’s energy and integrity, that he persuaded the rest of the fourteenth floor to let Fitzgerald have his own paper and stay on. Frank Packer was a man with a famously bad temper; but when Fitzgerald reported Henderson’s response, he took it with impressive geniality. His Observer began fortnightly on 22 February 1958, edited by Donald Horne in his spare time from producing the mass-circulation magazine Weekend. As proprietor of Australian Consolidated Press, publisher of the Australian Women’s Weekly as well as the Daily and Sunday Telegraph and Weekend, Packer had only to say the word and the Observer was viable. Fitzgerald, on the other hand, had to mortgage the family house at Abbotsford to get a loan of £5000 from the Commonwealth Bank as initial working capital for Nation.

That name came to him as he was walking home one night from the Herald. It was short, simple, declaratory — but modestly so: when asked why no definite article, he laughs and says that to call oneself The Nation would be presuming to be Australia.

Though he admired the American liberal weekly of that title, it was not in his mind as he named his own paper. Nor, at that moment, did he remember that in 1931 Keynes, the liberal master, had engineered the merger of another The Nation with the socialist The New Statesman, whose masthead still said The New Statesman and Nation. Had a sense of the Irish past deposited in his mind the name of the weekly founded in 1842 by Charles Gavan Duffy, later premier of Victoria? Certainly that had been simply Nation, like the paper Fitzgerald was now gestating.

In Australia The New Statesman and Nation, self-appointed and widely recognised as the conscience of British Labour, had been the great model for people on the left yearning for a journal of dissenting opinion. Voice had aspired to be its equivalent here, and so earlier had Allan Fraser’s Australian Observer. Fitzgerald was more ecumenical in his tastes, reading the Economist more attentively than most of his left-wing friends, enjoying the Spectator, and finding the Manchester Guardian the most congenial of English journals.

He thought highly of some New Statesman contributors, especially R.H.S. Crossman, and envied the paper its ability to command so many of the best essayists in the language to write for the literary pages. When the editor, Kingsley Martin, visited Australia soon after Nation was launched, he gave friendly counsel and wrote for it. But Fitzgerald’s respect for the New Statesman fell a long way short of idolatry. The paper had refused to publish his hero George Orwell’s anti-communist testimony from the Spanish civil war. Towards the United States it displayed an incurious prejudice compounded of anti-capitalism, little-Englandism and snobbery, filtering out the fecundity which had so enthralled Fitzgerald; unlike most New Statesman subscribers in this country he was a regular reader of liberal American weeklies, both The Nation and The New Republic. Hatching his own Nation, he told an American correspondent it would be “of the style of the New Republic,” its contributors “free to say anything they wish as long as it is substantiated by facts or backed by argument.”

Moreover, he was not a socialist. Though welcoming the Curtin and Chifley governments’ strategy of postwar construction and, more generally, applauding the policies of liberal welfare employed by Labour in the United Kingdom, the Democrats in the United States, and Labor here, he went no further than Keynes as an advocate of government intervention in the economy; and Chifley’s most drastic enterprise shocked him, for the time being, out of the Irish-Catholic habit of voting Labor he had acquired from his father. The nationalisation of banking was a question on which he had an open mind, though he believed that any government proposing it had to show good and clear cause. Chifley began quietly to legislate for it in 1947, having said not a word on the subject before the 1946 election, hoping that the abolition of private banks would be a fait accompli by 1949. On a matter of momentous public importance, the people were not being given a chance to decide; by 1949, so it seemed to Fitzgerald, Chifley and his allies would say, “It’s all over, mate.” In the event the legislation was stopped in the courts. But at the 1949 election Fitzgerald could not bring himself to vote for the party that had tried to slip it through.

Menzies back in office troubled Fitzgerald with the illiberalism of his Communist Party Dissolution Act and his subsequent habit of red-baiting as a substitute for hard policies at election time. He was dismayed at Menzies’s behaviour in the Suez crisis of 1956, as a naive and vain lackey of a doomed imperial cause, and in foreign policy at large Menzies seemed to him by now an archaic provincial Briton insensitive to the awakening of postcolonial nations, some of whom were Australia’s unheeded neighbours. Chifley and Evatt had shown promise of more enlightened approaches; but Labor was committed at least as solidly to White Australia. “In Australia the liberal has no party,” Nation would declare editorially, “and should never forget that” (20 March 1971). At the time the paper was launched, its proprietor’s best hope for national political life was that the Labor Party would climb out of the abyss into which it had been led in 1954–55 by ideological conflict, inept leaders and an adroit opponent, and discover a capacity to welcome the intelligence and idealism of Australians who had good reason to feel disfranchised, unrepresented either in parliament or in what passed for public discussion in the press. The daily papers were uniformly anti-Labor, docile in the face of Menzies’s posturings abroad, content with his government’s obsequious endorsement of American foreign policy in Australia’s region, slaves to the bipartisan conventional wisdom about non-European immigrants, and indifferent to large issues which seemed to Fitzgerald to cry out for scrutiny, such as the tendency towards monopoly in industry.

When he sought contributors, Fitzgerald was modest about the unborn paper’s personality. Sometimes he employed a homely simile which came to mind years later as he mourned Alf Conlon, disinterested intellectual and patriot (and in those respects an Australian Orwell), for pursuing the right without show or fuss, “as a man opens the windows in a stuffy room” (7 September 1963). “Stuffy” and “stodgy”: these were words he used when he thought both of the industry in which he worked and of the society it was supposed to be serving. “Australia was a stodgy place in the fifties,” said Fitzgerald looking back from 1984, “but one who remained firmly outside the stodge could find interest in observing it and giving it a stir.” He was speaking at the funeral of his closest comrade in the adventure of starting and sustaining Nation, George Munster.

The two men first met one evening at Lorenzini’s, a wine bar and coffee shop in lower Elizabeth Street, where Fitzgerald from time to time tried out his plans on a small group of friends, among them Maurice Isaacs, a solicitor active in Labor politics, Victor Worstead, a highly literate proofreader for the Sydney Morning Herald, Alex Sheppard, an intellectual bookseller, Sylvia Lawson, a young journalist and poet, and her husband Keith Thomas, a solicitor. Barry Humphries, at that time performing other people’s scripts in the Phillip Street Revue, sometimes joined the group; he seemed to Fitzgerald a young man with great passion. One night he said to Fitzgerald, “I want you to meet a friend of mine who’s a genius,” and introduced George Munster.

When Tom Fitzgerald was learning how to navigate bombers, George Munster was studying for the Leaving Certificate at Sydney Boys High, winning prizes for English, French and Latin and coming top of the state in the first two subjects. This made news because until 1939 George John Munster had been Georg Hans Münster, born in Vienna in 1925 to an Austrian Catholic mother and a Czech Jewish father. The family left Austria for Czechoslovakia early in 1938, just before Hitler’s army was invited in to “maintain order.” Father, an industrialist, risked going back to Vienna on business and was imprisoned, then released by virtue of his Czech passport. In February 1939 the Münsters — parents, son and daughter — got to London, and sailed for Sydney later that month on the P&O ship Narkunda. George Munster’s first English lessons were self-administered at sea.

In his funeral tribute Fitzgerald imagined the moment when Lord Wakehurst, governor of New South Wales, handed over the prizes on 16 December 1943:

There was the Establishment, out in force, beckoning recruits from the brightest young men to be replacements for their own high positions in the meritocracy… There is nothing to suggest that George ever entertained such ideas. A functionary’s role in the prescribed grooves, whatever the salary and prestige, had no interest for him. He would be a free spirit, occupied with more worthwhile concerns which would sometimes subvert the self-righteousness of members of the Establishment.

At the University of Sydney Munster studied English under Professor A.J.A. Waldock and philosophy under the iconoclastic Professor John Anderson (whose lectures Fitzgerald, to his later regret, never heard). He co-edited the annual magazine Hermes, and was one of a team of awesomely articulate youngsters on a popular radio program, Youth Speaks, with Eugene Kamenka, who became a professor in the History of Ideas at the Australian National University, Adrian Rodin, who became a judge of the NSW Supreme Court, and Neville Wran, who became premier. Munster graduated with honours in 1947 (a first in English, a second in philosophy), declined Waldock’s invitation to do postgraduate study in English, lectured for a while in English to ex-servicemen preparing to be undergraduates, and took off back to Europe in 1949. In London he did supply teaching; in Iraq he tutored in English for the British Council. “As George’s thought processes were both rapid and elliptical,” his friend Richard Hall wrote later, “it is intriguing to think what earnest Iraqis in search of self-improvement made of his lessons.” They and their families may have had some influence on him: Fitzgerald thought he saw an Arab element in the manner of the man he met at Lorenzini’s when he walked behind a companion as a mark of courtesy.

Munster had hoped Fitzgerald might help to get him some Herald book reviewing; but as soon as they began to talk about Nation, he offered himself for the project. A writer’s life had attracted him, and he had been working on a novel while living in the lighthouse at Barrenjoey, north of Sydney. He never wanted to be the employee of a newspaper proprietor. Nation was really the first thoroughly professional commitment of his life — though at this stage, curiously, he thought not of writing for the paper but of managing its affairs. He became Nation’s business manager, to the amazement of acquaintances who saw him as an unworldly participant in a continuous symposium where time was marked only by intervals to buy more cigarettes. He was also designated sometimes as associate editor.

Fitzgerald and Munster made a remarkably contrasting pair: native son of Sydney and cosmopolitan Viennese; neat Herald man in dark suit, unattached intellectual whose crumpled clothes looked as if he had been in them for a week. The Herald’s historian Gavin Souter saw Fitzgerald as having “the round, rosy face of a very shrewd-looking cherub.” If he was a cherub his companion was an imp; Munster could have been cast for a shadowy part in Carol Reed’s The Third Man. Labor leader Dr H.V. Evatt, by 1958 prone to see persecutors everywhere, said of him one night in Lorenzini’s: “That man is watching me, he’s an ASIO operator.” They were both keen and skilful watchers; they enjoyed laughing at the human comedy, Fitzgerald heartily and Munster in a sardonic chuckle. The business manager turned out to have no less than the editor what Souter described as “a fearless eye for business chicanery.” From different directions each had come a long way to work together subjecting Australian society, and especially the establishment, to close and lively scrutiny.

Each knew Sydney well. Concerned to find readers and therefore contributors in Melbourne, Fitzgerald set out for that city in mid 1958. It was unfamiliar territory. Having no taste for holidays, he travelled outside Sydney only when work for the Herald required, and that amounted to short visits once or twice a year. Landing at Essendon airport on the kind of bleak winter day Sydney people think typical of Melbourne, he had a glum feeling that this was going to be a terribly hard place to rouse. Its papers he knew as even blander than Sydney’s. Quickly, however, he had the sense of tapping a vein of subterranean radicalism that had no ready means of expression.

His first call was on Macmahon Ball, professor of political science at Melbourne’s university, who combined several qualities the paper was being designed to express: a mellow (but not stuffy) liberalism, an eloquent familiarity with Australia’s Asian and Pacific location, a will to educate the country’s political leaders (most of whom he knew well), a pen experienced in carrying thoughts from study desk to a general audience. He had been the ABC’s best-known commentator on affairs in Australia’s region until eased away from the microphone by pressure from Canberra, and he had written regularly for Voice. After a short conversation with Fitzgerald, whom he was meeting for the first time, Macmahon Ball not only undertook to write but had him meet likely contributors, among them his friend Peter Ryan and his colleague Alan Davies. Another Melbourne recruit was Cyril Pearl, who had retired when not quite fifty from the rough-and-tumble of journalism, after successful careers in Melbourne and Sydney, to live by writing clever and popular history books. Fitzgerald also visited Canberra, where Geoffrey Sawer, professor of law at the Australian National University, was among people who agreed to write.

Nation got its first Adelaide correspondent by telephone. One evening in August 1958 the operator there told me that Sydney was calling — a rare event — and I heard the gentle, civilised voice of a man introducing himself as financial editor of the Sydney Morning Herald and wondering if I would consider writing for a journal of opinion he was about to start. Back in Australia after three years in England, teaching in a university and wanting to communicate with people outside it, I had found nowhere really comfortable to write since Voice stopped. I contributed occasionally to Melbourne’s Age Literary Supplement, but that gave me little pleasure after I sent in a piece under the name of the Reverend somebody or other, on the Bee in Literature, parodying the supplement’s pretensions and banalities, which was duly published and apparently provoked not a soul to comment, though I had made up half the authors quoted. The literary quarterly Meanjin was the Australian publication most to my taste, and Fitzgerald happened to like a review I had done there of a book about Australian broadcasting. I agreed at once.

Some people asked about payment. Voice and its predecessors had paid little or nothing; academics, in particular, thought of writing for such a paper as a hobby or a community service. But Fitzgerald was looking for professional journalists and other people who would need to be paid rates similar to those paid by newspapers, as Packer’s Observer was already offering. So Nation was committed to payments of around £100 an issue (expressed, by literary tradition, in “guineas”) for contributors. How much Munster was paid Fitzgerald never knew: the proprietor/editor simply asked the business manager not to be stingy with himself. Money was a subject of mutual embarrassment. Marie de Lepervanche, who came to Nation as secretary just after the first issue, thinks that Munster took £20 a week and paid her £19, at a time when the basic wage for an unskilled male worker was around £18. She was a graduate in geology who had trained as a librarian after being unable to find work in a male-dominated profession. In the cause of efficiency and economy, she built the office filing cabinets out of fruit boxes from the market. She put cheques in front of Fitzgerald and Munster to sign — for contributors (including occasionally herself, when she reviewed a book), for part-time clerical help, for stationery and postage and agents’ distribution charges, and for printing, the largest item by far. There was at first no rent for premises: the printer supplied them free.

The printer was Francis James, born as Fitzgerald was in 1918 and also a wartime flyer, the son of an Anglican clergyman and pilot of fighters in the Royal Air Force, which he had joined after sailing for England the day war began. He boasted of having been expelled from five schools, and he was certainly sent down after the war from Balliol College, Oxford. He was a man of panache and mystery. A wide-brimmed black felt hat and dark glasses conveyed both, while actually protecting eyes so badly damaged when his Spitfire was shot down in Germany that he was declared (after escaping back to England) permanently and totally incapacitated. That did not stop him running a fishing business in Albany, becoming religious and educational correspondent of the Sydney Morning Herald (where legend says he made his office in an old Rolls Royce parked outside), and creating the Anglican, a weekly with the tone of the Times which scourged the evangelical diocese of Sydney in the name of a high church tory radicalism. James and Fitzgerald had become close friends after meeting at the Herald. At this historic moment for intellectual journalism in Australia James enjoyed the role of double agent. Though the Observer and Nation carried the names of different presses, they were both produced at James’s printery.

Nation was “Set up and printed by Caslon Press for the publishers, Nation Review Company, 39 Walton Crescent, Abbotsford, New South Wales.” Caslon Press was one of the names Francis James gave his printery. (Times Press was another, which after a while he used for Nation.) Nation Review Company was T.M. Fitzgerald, and 39 Walton Crescent was the house he had mortgaged. His friend and honorary solicitor Maurice Isaacs, worried about what might happen to the house, advised him to incorporate Nation and thus limit his liability. Fitzgerald preferred to leave it as his personal property and offset anticipated losses against his salary as tax deductions. The bold title block, by Rod Shaw, was designed to make the paper readily visible on newsstands.

The first issue of the Observer had been delayed because it was printed back to front. The first Nation was supposed to come off the press late on a Thursday evening but in the event took all night. Tom Fitzgerald and Sylvia Lawson were there until dawn, having persuaded George Munster to go home and get some sleep. Francis James conducted proceedings in his RAF voice and silk dressing gown. The issue was dated 26 September 1958, just a month late for its creator’s private deadline of his fortieth birthday. •

This is the introduction to Nation: The Life of an Independent Journal of Opinion 1958–72, published by Melbourne University Press.