The politics of property prices are shifting rapidly beneath the Turnbull government. After declaring that housing affordability would be the centrepiece of next month’s federal budget, the government has been backtracking.

The shift in rhetoric isn’t surprising. Despite all the talk of options on the table, the government is yet to show that it’s serious about addressing housing affordability. Few of the proposals it has flagged in recent weeks would make much difference, and some would make the problem worse.

To capitalise on the government’s indecision, the opposition announced its own housing strategy last week. While most of Labor’s ideas are sensible, not many will make housing much more affordable, with the exception of previously announced changes to negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount.

State and federal governments have raised expectations among voters anxious to see action on housing. Governments now need something concrete to point to. There are options that would make a big difference, but none is politically easy. If governments want to be seen to be serious about housing affordability, they’re going to have to make tough choices and avoid the temptation to do the easy (and stupid) things.

The first step to making housing more affordable is to face up to the size of the problem. Australian house prices have more than doubled in real terms since the mid 1990s, far outstripping growth in household incomes. And while low interest rates make it relatively easy to service a loan today, slow wages growth means that the burden of a mortgage is eroded more slowly than in the past. Home ownership rates are falling, especially among the young and the poor. Without change, many young Australians could be locked out of the housing market.

Governments have long promised to improve housing affordability, yet all the while house prices have continued to rise. The politics are hard. More Australians own a house than are seeking to buy a house, and making housing more affordable means house prices will be lower than would otherwise be the case. And many people who live in the established middle suburbs don’t like the idea of more density in their neighbourhoods. If governments really want to make a difference, they need to explain why improving housing affordability matters – and why doing nothing will only make the problem worse.

While making the hard decisions, governments should also set realistic expectations. Although government policy can help, housing is unlikely to become much more affordable overnight. It took neglectful governments two decades to create Australia’s housing affordability crisis, and it will take just as long to improve matters. There are limits to what even a brave government can do.

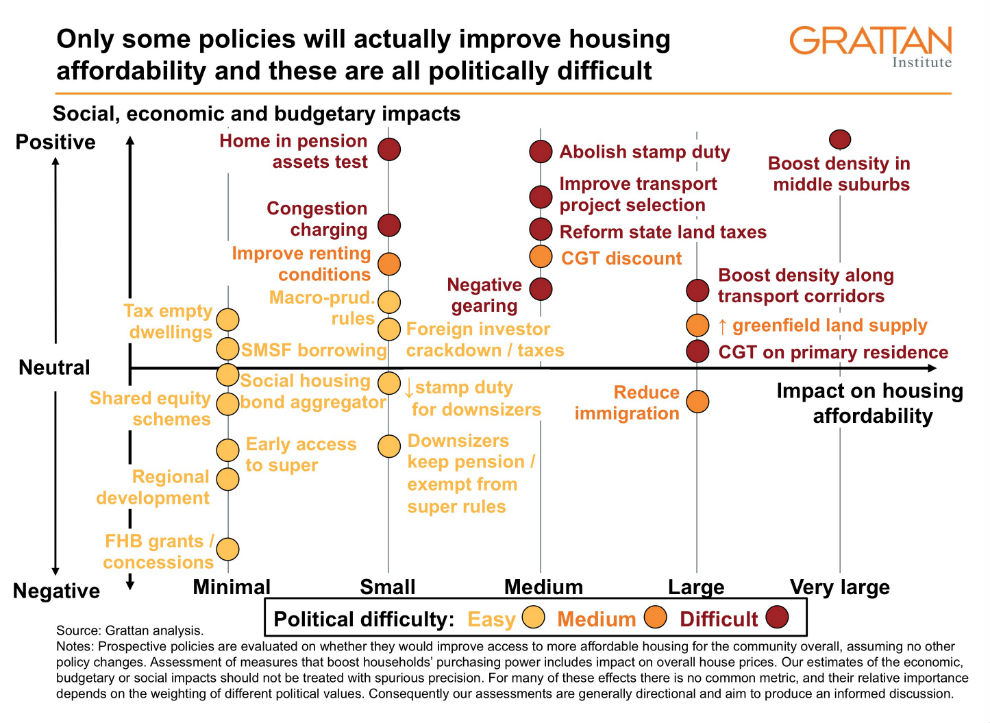

A lack of policy ideas isn’t the problem. There are plenty, but most of them simply won’t have much effect. Some will make housing affordability worse, drag on economic growth, or subtract from government budgets that are already in trouble. And a few will make a difference, but all of them are politically difficult.

The policies that sound good, but won’t help much in practice, live in the top left of our diagram.

Treasurer Scott Morrison has shown great interest in “shared equity” schemes, which sound like a way for first home buyers to clear the deposit hurdle without significant costs to taxpayers. Such schemes come in many shapes and sizes, but in this case the government would likely stump up some of the capital to purchase a home, and later, when the property is sold, it would get its money back, together with a share of any property price growth. Such schemes already exist in Western Australia and South Australia, where government lenders have issued thousands of loans for people to purchase their own home.

There is some evidence that these schemes increase home ownership rates. Yet they are unlikely to make much of a difference to housing affordability, at least not without big public subsidies. Only one-in-five loans approved by the WA lender in 2015–16 were genuine shared-equity loans. Most were low-deposit loans to borrowers, some of whom may have borrowed from a commercial bank.

Treasurer Morrison is also keen on a “bond aggregator” for the social housing sector. The government would borrow on behalf of community housing providers, and on-lend to the providers – giving them access to cheaper and longer-term finance. While this may help to boost the supply of social housing, a substantial increase in the stock is unlikely unless there are additional large public subsidies to cover the costs of providing housing at below-market rents.

Restricting foreign investment in housing may have some impact on house prices, but again only at the margin. Treasury research suggests that foreign investment has not been a major contributor to recent growth in house prices. Of course, the government should ensure that foreign investment rules are being followed; recent reports suggest that foreign investment rules are still being broken, despite a recent crackdown.

Increasing taxes on foreign investment in housing, as several state governments have already done, and federal Labor has now proposed, may be a sensible way to raise revenue, but it is unlikely to hit house prices unless the tax hikes are very big.

Taxing vacant dwellings, a policy recently announced by the federal opposition and the Victorian Labor government, sounds attractive, but will be difficult to administer. Accountants are likely to be able to fit most vacant homes within one of the exemptions for those temporarily overseas, holiday homes and those who need a city unit for work purposes. A similar tax introduced in Vancouver this year is yet to show that it has overcome these challenges.

While those ideas won’t do much to make housing more affordable, they won’t do much harm either. Several other ideas, shown in the bottom left of our diagram, are less benign: they involve big risks either to the budget or to the economy.

The Turnbull government is reportedly still considering allowing people to use their superannuation to buy their first house. Politicians are understandably attracted to any policy that appears to help first home buyers build a deposit. Unlike the various first home buyers’ grants, which cost billions each year, letting first home buyers cash out their super would not hurt the budget bottom line – at least in the short run. But as we wrote in 2015, such a change would push up house prices, leave many people with less to retire on, and cost taxpayers in the long run. Alternatives that allow first home buyers to withdraw only voluntary super contributions are less foolish, but are unlikely to make much difference to housing affordability.

Another proposal to give first homebuyers extra tax incentives to save for a home has similar problems – it would move taxpayer money into the pockets of vendors without addressing affordability. In fact we’ve been here before: the former Rudd government’s First Home Saver Accounts provided similar financial incentives to help first homebuyers build a deposit. Treasury expected A$6.5 billion to be held in First Home Saver Accounts by 2012. Instead only A$500 million had been saved by 2014, when Joe Hockey abolished the scheme, citing a lack of take up.

The government is reportedly considering providing incentives to encourage seniors to downsize their homes, thereby freeing up larger homes for younger Australians. This idea, too, should be rejected. Research shows that downsizing is primarily motivated by lifestyle preferences and relationship changes. These considerations dwarf the financial trade-offs between having more cash to spend, but a lower age pension. According to surveys, no more than 15 per cent of downsizers are motivated by financial gain. Stamp duty costs (which are analogous to the threat of losing pension entitlements) were a barrier for only about 5 per cent of those thinking about downsizing. If financial considerations aren’t the big barrier then many of the incentives would go to households that would have downsized anyway. As the Productivity Commission found, these incentives have a material budget cost, and distort the housing market by adding even more to the long-term tax and welfare incentives to own a home.

The government should also resist the temptation to push people to the regions. Since Federation, state and federal governments have tried to lure people, trade and business away from capital cities. It has invariably been an expensive policy failure. Despite government policies of decentralisation, the trend to city-centred growth has accelerated in the past decade. Half of all net jobs growth in Melbourne and Sydney is now within a two-kilometre radius of the city centres, reflecting the rapid growth of jobs in service industries, where physical proximity really matters. In the unlikely event that government policy actually succeeded in encouraging more people to live in regional areas, it could reduce house prices in the major cities, but it would also slow growth in incomes.

The government should also tread carefully when it comes to curbing immigration, as proposed by former prime minister Tony Abbott. Slowing immigration would have a big impact on house prices. Australia’s resident population is increasing by about 350,000 a year, and over half of this is due to immigration. But curbing migration could also slow growth in incomes. Recent Productivity Commission modelling concluded that continuing Australia’s approach of taking younger, skilled migrants could result in GDP per person being up to 7 per cent higher in 2060 than if there were zero net migration.

So governments need to focus on the policies in the top right of our diagram: policies that will make a material difference to affordability without substantially dragging on the economy or the budget. Everything in this category is politically difficult.

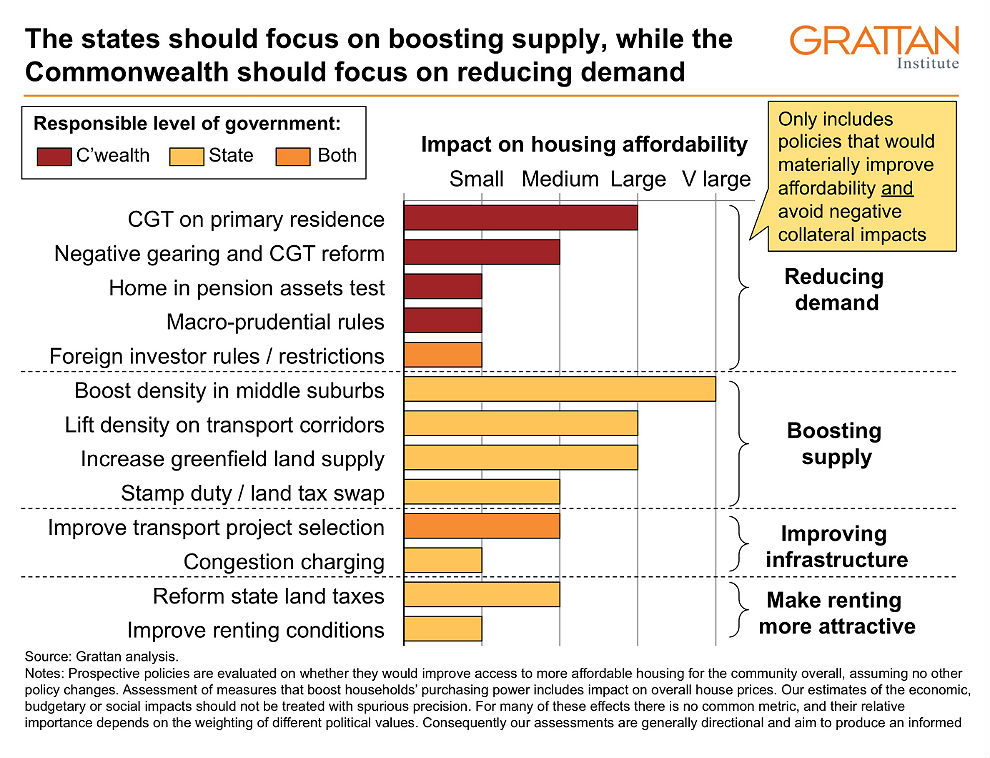

Given the allocation of federal responsibilities, the Commonwealth can primarily intervene to reduce demand. States have more ability to boost supply, through land-use planning and zoning laws, and by releasing greenfield land. They can also make renting more attractive by reforming state land taxes and residential tenancy laws. Both levels of government can improve access by making better decisions about which transport infrastructure to build, and then introducing congestion charges.

The most obvious way the Commonwealth government can materially reduce housing demand is by reducing the capital gains tax discount and abolishing negative gearing. The effect on property prices would be modest – they would be roughly 2 per cent lower than otherwise – but would-be home owners would benefit. Economic benefits would flow too. The current tax arrangements distort investment decisions and make housing markets more volatile. Reform would boost the budget bottom line by around $5 billion a year. Contrary to urban myth, rents wouldn’t change much, nor would housing markets collapse. If phased in, the reforms would be easier to sell politically and would dissuade investors from rushing to sell property before the changes come into force. An alternative flagged by the government – limiting the number of properties a person could negatively gear – would be much less effective because few people negatively gear multiple properties.

The government should also include the value of the family home above some threshold – such as $500,000 – in the age pension assets test. This would encourage a few more senior Australians to downsize to more appropriate housing. More importantly, it would make pension arrangements fairer, and contribute up to $7 billion a year to the budget.

Making owner-occupied housing liable for capital gains tax could also reduce demand and improve the budget bottom line. But such a change might have unintended consequences. It would discourage people from moving house, since home sales would trigger liability to pay capital gains tax. Young purchasers would be tempted to choose oversized housing to reduce the number of home moves they make over a lifetime. It would be difficult to resist calls to allow deduction of interest payments (given taxation of the gains), which would wipe out most of the benefit to the budget.

Affordability would improve much more if the states did the heavy policy lifting over a number of years to increase supply.

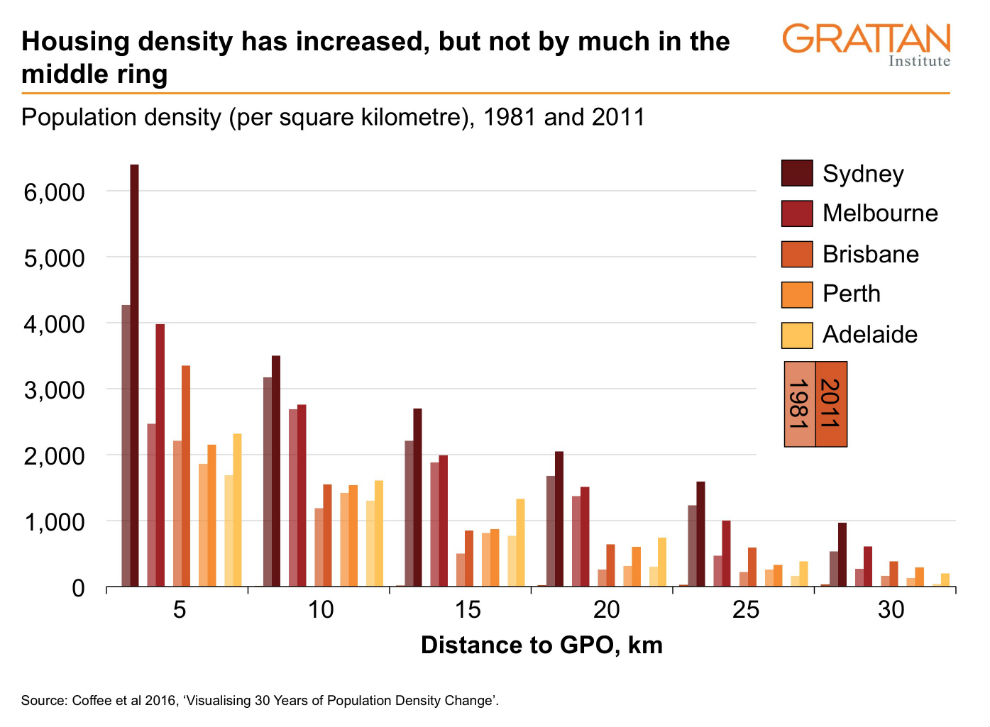

The middle rings of Australia’s large capital cities generally have good infrastructure, and good access to city centres, where most of the new jobs are being created. These cities are sparsely populated relative to other large cities in the developed world outside the United States. Grattan Institute research shows that people want more townhouses and semi-detached dwellings in established suburbs.

Current rules make it reasonably easy to build apartments in the CBD and to develop new housing estates on the fringes of the major cities – so that is what we’re getting. But the rules make it very difficult to subdivide and create extra residences in the middle rings of the capital cities, up to twenty kilometres out of the CBD. Population density in the middle rings has hardly changed in the past thirty years, yet urban infill could supply a lot of the new housing needed.

State and local governments need to change planning laws and practice to make it easier to subdivide in middle-ring suburbs. They also need to increase density along transport corridors, which would both boost housing supply and use existing transport infrastructure better.

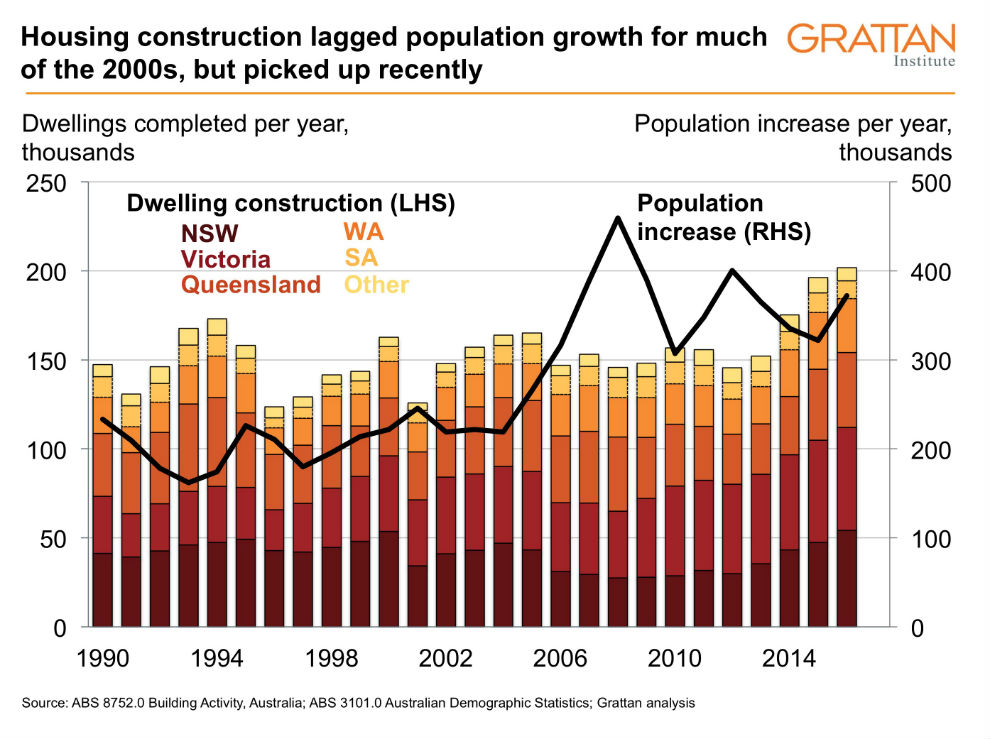

Increasing supply will only restore housing affordability slowly. With migration increasing substantially from about 2006, Australia’s population grew by around 350,000 per year, rather than the 220,000 per year that was typical in the previous decade. Dwelling construction did not match demand, particularly in New South Wales. It increased by about 30 per cent in the past four years, but it is still only keeping pace with current population growth. Several years of construction – probably at even faster rates than currently – will be needed to erode the large backlog that accumulated between 2006 and 2014, estimated to be a shortage of about 200,000 dwellings.

This is primarily a state government problem. While the federal government can release some of the limited stock of Commonwealth land, it does not directly control planning rules. It could provide incentives to state and local governments to increase the supply of housing in good locations, but its budget will struggle to provide incentives sufficiently large to overcome the reluctance of a state government that is not motivated to take on the political difficulties anyway.

State governments should also abolish stamp duties and replace them with a general property tax, as the ACT government is doing. Stamp duties on the transfer of property are among the most inefficient of taxes: they discourage people from moving to better jobs, or to housing that better suits their needs. Their abolition would encourage people to move as their circumstances change, making more efficient use of the housing stock. This would mainly improve economic growth rather than housing affordability, but it’s a big prize: a national shift from stamp duties to a broad-based property tax could add up to $9 billion a year to gross domestic product.

Reform of progressive state land taxes, which levy a higher rate of land tax if a person owns more investment property, could improve conditions for renters, because institutional investors would be more likely to offer long-term leases to those renters who seek greater certainty.

Such tax reforms might be encouraged if the federal government provided incentive payments to the states, which would reflect how Commonwealth revenues will ultimately benefit from the increased economic growth. A recent COAG agreement to encourage states to enact economic reforms is a step in the right direction, but more needs to be done.

Governments also need to improve transport networks by using existing transport infrastructure more efficiently and building more effective transport projects. This will make fringe suburbs a more attractive alternative to established suburbs closer to CBDs, limiting price increases in inner suburbs.

First, the federal government should work with states on the possibility of introducing congestion charging to ensure existing roads are used more efficiently. A congestion charge needs to discourage only a small proportion of people from driving to enable a big increase in traffic speed.

Second, the way governments decide on transport infrastructure investment needs to improve. Governments have tended to favour projects in swing states and marginal seats, rather than projects with the highest benefit–cost ratios. They should only commit money to a transport infrastructure project if Infrastructure Australia or another independent body has assessed it as high priority, and the business case has been tabled in parliament.

Housing affordability has vexed Australian governments for two decades, as politicians have tried to appease aspiring first home buyers without upsetting existing home owners. They have dodged the hard choices that would actually make a difference, preferring policies that are cosmetic but politically painless.

Continuing inaction will further reduce home ownership, increase inequality, dampen economic growth, and increase the risks of an economic downturn. The public has figured out that there is a real problem. Unless governments improve the reality rather than appearances, public trust in political institutions will continue to fall. Pretending there are easy answers will only make things worse. •