When more than a thousand delegates gathered in Darwin last week for Australia’s biennial national housing conference, they were welcomed by no fewer than three federal government ministers.

By video, prime minister Scott Morrison, champion of “quiet Australians,” invoked the “homes material, homes human and homes spiritual” of Robert Menzies’s forgotten people broadcast to remind attendees that “housing is much more than a roof over your head.” Also by video, housing minister and assistant treasurer Michael Sukkar declared that the government’s priority is to “reduce pressure on affordability” and pointed to the first home loan deposit scheme and other Coalition campaign promises. In person, assistant housing minister Luke Howarth, whose responsibilities include community housing and homelessness, stressed that the government is aware of the shortage of social and affordable housing and “wants to get some wins in this space.”

All three ministers lauded the policy-oriented research of the conference organiser, the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, and praised the practical efforts of the housing and homelessness workers who attend each year in large numbers. None of them offered any new initiatives.

Like climate change, housing is in the political too-hard basket, acknowledged as a pressing national problem but tackled in a piecemeal and ad hoc manner. There’s no mystery about why: a comprehensive response would cost a lot of money and upset core constituencies.

Perhaps this is what induced Luke Howarth’s clumsy attempt to put “a positive spin” on homelessness recently. Only a “very, very small percentage of the population” is affected, he told Radio National Breakfast, and “parts of homelessness” have actually “reduced.”

Technically, he’s right. The number of people counted as homeless in the 2016 census represented 0.5 per cent of the population — a small, though not negligible, minority. And while homelessness was higher than in the previous census, the number of rough sleepers had fallen. It was other forms of homelessness, especially severe overcrowding, that got worse. Indigenous homelessness was also down, though the rate among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people remains ten times higher than for non-Indigenous Australians.

On Radio National, Mr Howarth also rejected the idea that Australia has a housing crisis. At first glance the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics data on housing occupancy and costs seems to support that view too. Home ownership might have declined slightly, but two-thirds of Australians still own their own homes. On average, keeping a roof over your head is no bigger burden on your household budget —around 13–14 per cent of gross income — than it was a decade ago. Rising house prices may have forced buyers to take out larger mortgages, but falling interest rates have brought down the cost of servicing loans.

So we might be tempted to ask, along with the assistant minister: Crisis? What crisis? But it’s more appropriate to ask: Crisis? Whose crisis?

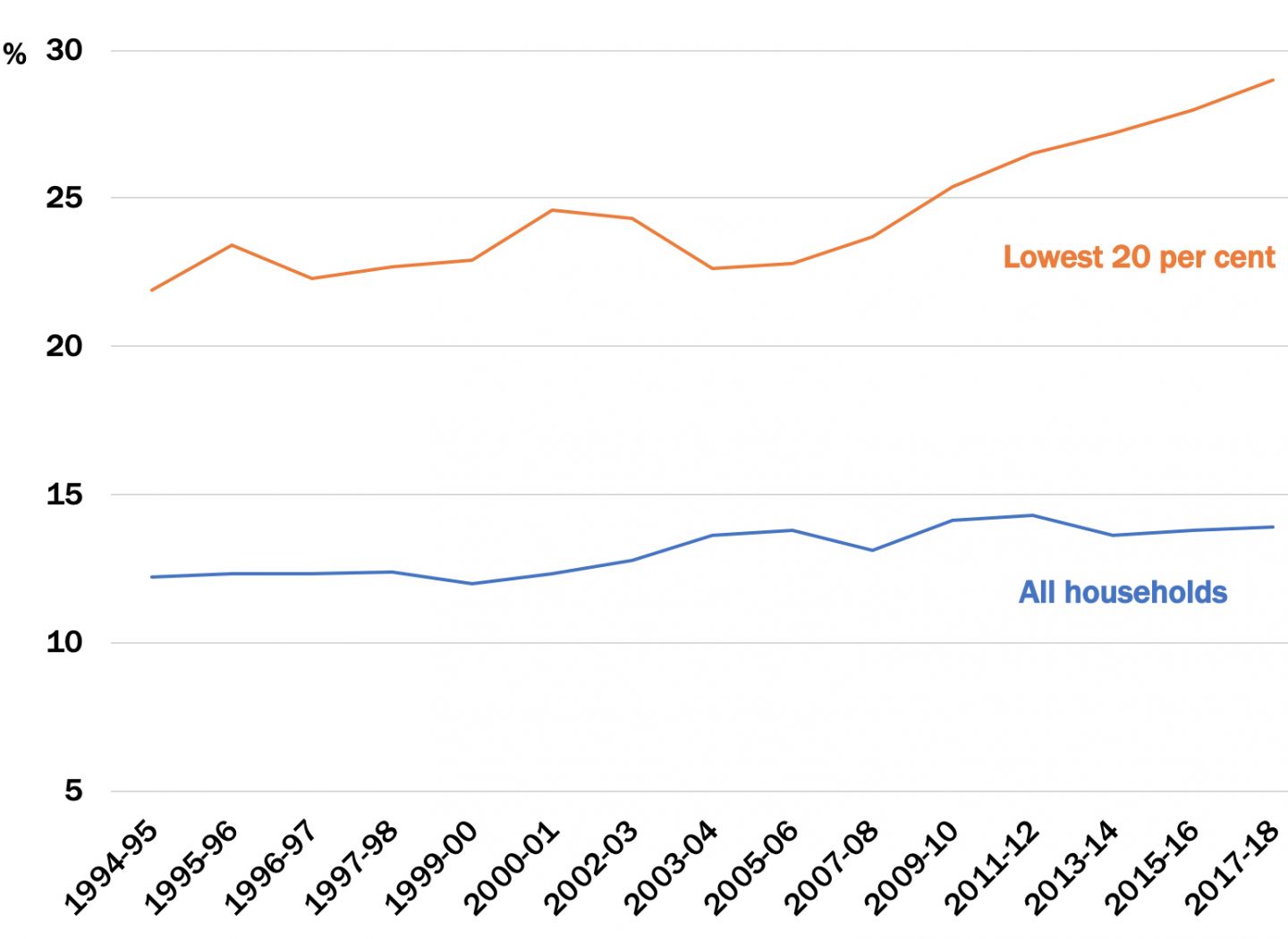

Housing costs for those on the lowest incomes — the bottom fifth of households — have risen dramatically from 22 per cent to 29 per cent of gross income. Tenants in the private rental market haven’t benefited from falling interest rates, and rents have risen faster than incomes — especially with wages and government payments stagnating over the past decade.

Housing costs as a proportion of household income, 1994–95 to 2017–18

Source: ABS 41300, Table 1, Housing Occupancy and Costs, Australia, 2017–18

The result is high levels of rental stress, now affecting 57 per cent of low-income households in the private market. This means that about 600,000 households with an “equivalised disposable income” below $775 per week hand over at least 30 per cent of that income to their landlord (and often much more than that). At the conference, Wendy Hayhurst from the Community Housing Industry Association described homelessness as “the tip of a rental stress iceberg,” and the group experiencing the most rapid increase in homelessness is older women, often as a result of the compounding effects of poverty and relationship breakdown (frequently caused by domestic abuse).

If people are spending a large proportion of their income on rent, that’s money they aren’t spending on goods and services in other parts of the economy. (Most landlords don’t spend their rent income either, but use it to pay down mortgages.) Renting in the private market on a low income not only shrinks the budget for other essentials like heating and healthy food, but means that the housing itself is insecure and unhealthy too.

The conference heard that the Warm Up New Zealand Program, which improves insulation in rental properties, has a benefit–cost ratio of four to one. It has been shown to significantly reduce hospital admissions, with the greatest benefits going to the poorest tenants, and to elderly people and children. Even though Luke Howarth said he was keen to hear positive ideas from the conference, the legacy of Australia’s “pink batts” controversy is likely to prevent governments from replicating such a commonsense program here.

Against the vociferous objections of landlords, New Zealand is also enforcing minimum standards in private rentals to ensure that housing is “warm, dry, safe and stable.” As Patrick Veyret from the Australian consumer organisation Choice told the conference, tenants here have more recourse against a mouldy loaf of bread than they do against a mouldy rental property.

The problem for low-income earners is compounded by the fact that they are competing for tenancies with a growing number of higher-earning people who are staying in the private rental market because they can’t scramble into home ownership. This is the phenomenon that lies behind terms like “generation rent,” the cohort of Australians seemingly locked permanently out of home ownership. But viewing the problem solely through a generational lens is misleading: as the Grattan Institute noted in its recent Generation Gap report, home ownership is “dropping fastest for the young and the poor.”

The flipside of generation rent is generation landlord. Australian Tax Office statistics show that the number of individuals reporting an interest in a rental property has been rising rapidly, with the fastest growth among people with an interest in multiple rental properties. The number of investors declaring an interest in three or more properties has grown 40 per cent in a decade. Government ministers are fond of pointing out that 70 per cent of investors own just one property. This is true, but from the tenants’ perspective, they are just as likely to be renting from a landlord who owns two or more properties as from “mum and dad” investors.

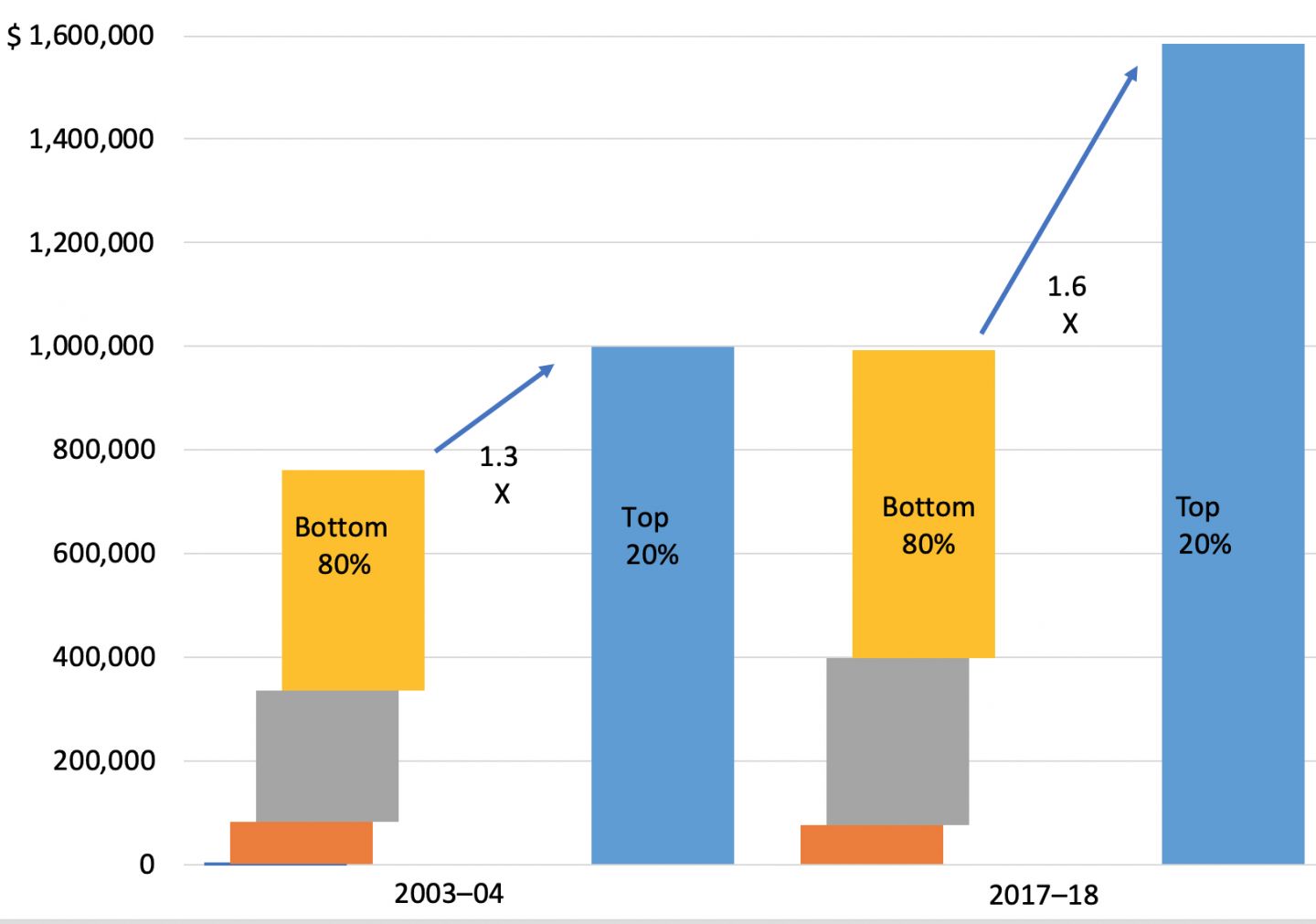

People who already have property are able to acquire more as they borrow against existing assets. The rich are getting richer, and my calculations from the latest ABS data show that housing plays a big role. In 2003–04, the mean value of the property owned by the wealthiest fifth of Australian households was worth 1.3 times as much as the mean value of the property owned by all other households combined. By 2017–18 that multiple had blown out to 1.6 times.

Average property wealth, 2003–04 to 2017–18: the rich versus the rest

Sources: ABS 6554.0 Household Wealth and Wealth Distribution, Australia, 2003–04, Table 6. ABS 6523.0 Household Income and Wealth Australia 2017–18 Table 7.2. Note: Property assets minus property liabilities.

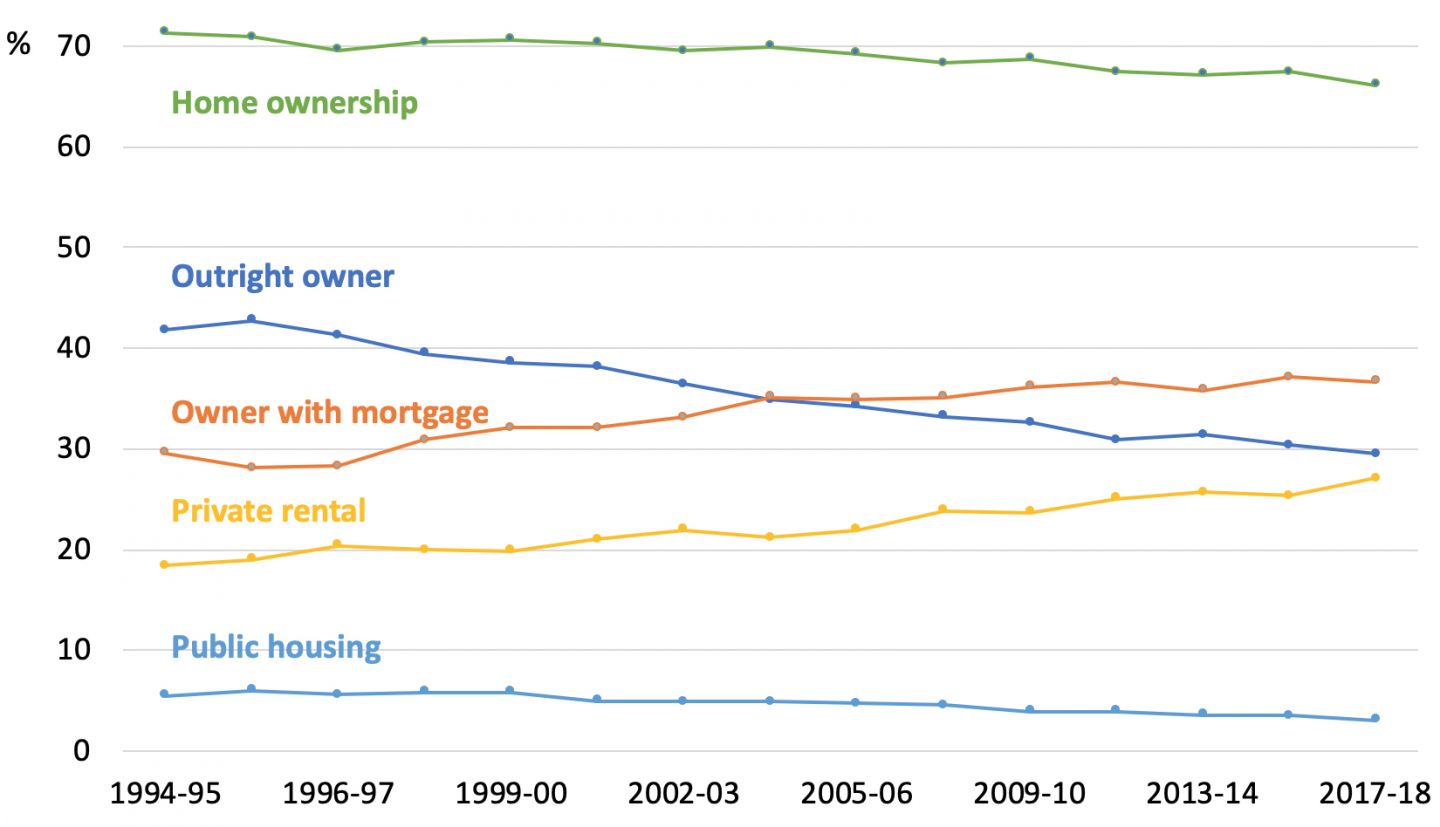

While home ownership is falling relatively slowly, the share of Australians who own their homes outright is falling much faster. On current trends, the number of Australians who own outright will soon be overtaken by the number who rent in the private market.

Shifts in housing tenure, 1994–95 to 2017–18

Source: ABS 41300, Table 1, Housing Occupancy and Costs, Australia, 2017–18

As new AHURI research shows, this has profound implications for future welfare spending. First, homeowners entering retirement (or prematurely forced out of the workforce) may be tempted to use their super to pay off their mortgages and then qualify for the age pension. Second, there will be more low-wage earners leaving the workforce without owning a home at all. As renters in the private market, they will become eligible for both the pension and Commonwealth rent assistance. According to the AHURI, the combination of ageing and declining home ownership will be a “seismic shock,” bringing a 60 per cent increase in the number of seniors eligible for rent assistance by 2031.

The budget cost of rent assistance has already jumped from $2.8 billion to $4.6 billion since 2008. Interestingly, a senior Canberra official at the conference couldn’t answer a question about future projections for spending on Commonwealth rent assistance, but we can expect it to keep going up.

Changes in demography and housing tenure are not the only factors. Another driver is the transfer of public housing stock from state-owned authorities to not-for-profit community housing associations. Ten years ago, Australia’s housing ministers agreed that community housing should make up 35 per cent of all social housing. With little money available for new housing, this target could only be met by moving thousands of dwellings into community hands. In the process, thousands of tenants became eligible for rent assistance for the first time. (Tenants in state-run housing don’t qualify, but tenants in community housing do.)

The continuing transfer of social housing stock from state to community hands seemed to be taken as a given by most conference delegates, including housing officials from all jurisdictions. But there are mixed motives behind these transfers. One aim is to boost the community housing associations’ asset base so that they can leverage more funds. Another aim reflects the view that community housing providers are more efficient and innovative than public authorities and cater better to tenants’ needs and interests. It’s certainly true that surveys consistently report higher levels of tenant satisfaction in the community sector.

Equally, though, the transition to community management shifts costs and liabilities off the states’ balance sheets. One community association in regional New South Wales has seen its housing portfolio grow 170 per cent in twelve months as a result of stock transfers, but most of the dwellings it has acquired are already forty years old. As buildings age, maintenance costs increase. Old public housing stock may have been designed to house families, which means it won’t be appropriate for the six in ten social housing tenants who live alone. Or it may not be accessible for the one in three tenant households that include someone with a disability. Where the funds to refurbish or replace these houses will come from is far from clear.

The solution to this problem is supposed to be the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation, a relatively new means of channelling investment into community housing. An initiative of Scott Morrison when he was treasurer, the NHFIC was variously described at the conference as “a game changer” and “the one bright spark” in housing policy in recent years, though even its biggest enthusiasts stressed it is only one part of the housing jigsaw.

In his address, Luke Howarth spruiked NHFIC’s debut $315 million bond issue, which was four times oversubscribed. So far, though, apart from one construction loan to build ninety-three new affordable dwellings in Sydney, NHFIC’s main role has been to enable community housing providers to refinance their existing debts at lower rates.

For two of Australia’s larger housing providers, one in Victoria and another in New South Wales, refinancing using the NHFIC bond has freed up about $1 million a year for new spending. Another talks of saving $6 million over ten years. These are welcome amounts, but just a small fraction of overall need.

Social housing is in long-term decline, falling from about 6 per cent of all households to about 4 per cent over the past twenty years. Housing finance expert Judy Yates calculates that if we want to restore the share of social housing to the level of 1996, then we need to build 16,500 new dwellings every year for the next twenty years. To meet the total projected shortfall of more than 700,000 dwellings, the City Futures Research Centre at the University of New South Wales estimates that we need to build 36,000 units annually. By way of comparison, about 3000 units of social housing were built last year.

The last major injection of funds — Kevin Rudd’s 2009 stimulus package in response to the global financial crisis — built about 19,000 homes. His National Rental Affordability Scheme resulted in 38,000 new dwellings over ten years, but this was mostly “affordable” rather than “social” housing. (Under charity rules and NHFIC’s guidelines, affordable housing must be offered at a 20 per cent discount on market rates, which can still be very expensive in major cities or tourist towns. Tenants in social housing, on the other hand, pay a fixed 25 per cent of their income in rent, regardless of location.)

These are early days, but NHFIC will only increase the stock of community housing by about 560 dwellings in its first twelve months. If it is going to enable the scale of building Australia needs, then it needs to unlock vastly larger amounts of funding. A secure return above 4 per cent could attract billions of dollars from Australian superannuation schemes and overseas pension funds seeking safe, long-term investments. But community housing associations can’t generate adequate returns by housing people on the lowest incomes. As Bill Randolph from the City Futures Research Centre put it, “there is always a gap” between the cost of building and maintaining social housing, and the rent that the lowest-income tenants can afford to pay. Modelling by Randolph and his colleagues shows that the average gap is about $12,000 a year, even with discounted finance via NHFIC and the added income flowing to community housing tenants from Commonwealth rent assistance. The gap will be larger in city centres, where land is expensive, or in remote Aboriginal communities, where building costs are particularly high.

There are many ways to bridge this gap. The cheapest option would be for government to fund more social housing with up-front capital investment, but this is not politically palatable. Governments — state, federal and local — could also provide vacant or underutilised land for community housing on a long-term peppercorn lease. Or Australia could adopt a version of the tax credit scheme used to encourage investment in affordable housing in the United States.

Another option discussed at the conference was Jacqui Lambie’s proposal that the federal government waive state and territory housing debts so that money can be spent on new dwellings instead of repayments to Canberra. But evidence from South Australia suggests caution here. That state managed to get the Commonwealth to wipe hundreds of millions of dollars off its debt in 2013, when Labor’s Mark Butler was federal housing minister. But an SA official told the conference that increased social housing investment didn’t follow. Instead, the savings were banked by the state treasury and spending on social housing actually fell.

Regardless of how the funding gap is bridged, any government subsidy needs to be stable, predictable and bipartisan so that it can survive a change of government. One-off programs with limited time horizons won’t be sufficient. “How have other countries unlocked affordable housing supply?” asked Carrie Hamilton from the Housing Action Network. “In every single case it has been credible permanent programs of national government subsidy.”

To fulfil election promises, NHFIC is getting an extra $25 million to administer the government’s first home loan deposit scheme and to take on a new research role. The scheme will enable purchasers with a 5 per cent deposit to get into the market without paying mortgage insurance, and the government hopes it will assist 10,000 first homebuyers each year. The research will focus on housing demand, supply and affordability with the explicit aim of ensuring that “owning your own home stays within the reach of most Australians.” Expanding the supply of affordable rental housing for those on the lowest incomes is not a priority. As Ken Marchingo, CEO of the Victorian community housing provider Haven Home Safe commented, “What we get is $25 million worth of research when what we need is $25 billion worth of new housing.”

Given its Darwin location, the conference had a strong focus on Indigenous housing. Under a ten-year agreement and a fifty–fifty funding split with the federal government, the Northern Territory is investing $1.1 billion in remote Aboriginal housing, with the aim of reducing the chronic overcrowding that contributes to easily preventable illnesses. The program has a big emphasis on training and employing local workers and encouraging the development of Aboriginal enterprises.

It’s a promising initiative, but hard-won. Jamie Chalker, the Territory public servant overseeing the program, ended the conference with an impassioned plea to delegates to tell the truth about what they had learned in Darwin: that the Territory has twelve times the rate of homelessness and twenty-two times the rate of overcrowding of the rest of Australia, and that it is a world leader in rheumatic heart disease. Given there have been six reviews of remote Aboriginal housing, he left his audience in no doubt that a Commonwealth contribution of $550 million over ten years is woefully inadequate.

Still, the Territory has done better than other jurisdictions since the expiry of a ten-year national remote-housing partnership in June 2018. Western Australia has managed to negotiate a one-off payment of $121 million from Canberra, South Australia has secured $37.5 million over five years, and there is still no deal in place in Queensland. Overall, says Labor senator Malarndirri McCarthy, remote Aboriginal housing remains a “wicked mess.”

The same term could be applied to social housing in general. There is a glaring need for public investment of at least $5 billion a year to meet the urgent housing needs of people on the lowest incomes. If Labor had won the federal election, its reforms to negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount could have raised revenue on this scale. But it lost, and tax reform is off the agenda.

Significantly, not a single presentation at the conference discussed tax settings. The Coalition says it is open to new ideas but only appears to be interested in initiatives that don’t cost much. The refusal to raise the level of Newstart payments shows that the government has no inclination whatsoever to increase social spending. Neither the Commonwealth nor most of the states and territories have clearly articulated targets for increasing the share of social housing or even for preventing it from declining further.

Even if we don’t invest in social housing, though, we are going to spend a lot more public money on housing anyway. We’re just going to spend it in different, less effective ways: on more rent assistance, more welfare payments, more homelessness services, more visits to emergency departments, more Medicare claims, more police and ambulance call-outs, and more people going through the courts and being put in jail. And tax revenue will be lost as a result of lower employment and declining productivity.

As Scott Morrison said, “housing is much more than a roof over your head.” It is also essential economic infrastructure, the foundation of good health, a building block for educational success, and the cornerstone of flourishing communities and flourishing lives. •