ON a beautiful early spring day in Shanghai, the shiny new shopping malls on the recently reconstructed Sichuan North Road, in the city’s Hongkou district, sparkle in the afternoon sun. But just round the corner, many of this neighbourhood’s residents are converging on an old, narrow residential lane where the 1920s grey-brick houses still cast a chilly shadow. Some come on foot, some by motorbike, some on creaking old upright bicycles; a few are in their twenties, many are middle-aged; there are old men in wheelchairs and elderly women walking with sticks.

These are people who haven’t benefited greatly from the spectacular economic growth that’s made Shanghai a focus of global attention over the past decade. Many are laid-off workers from state-run textile and chemical factories, which were once the mainstay of the economy in this part of the city; some have menial jobs; others are retired on small pensions. Most are tenants of the government, many living (and sharing kitchens and bathrooms) in cramped rooms in houses built for single families in the 1920s and 30s.

But that’s exactly why they are here today. Embarrassed by criticism that housing prices – which have increased eight- to tenfold, on average, over the past decade – have made modern housing inaccessible to many ordinary people, Shanghai, like the rest of China, is beginning to roll out its first new batch of “affordable housing.” Applications are being accepted at neighbourhood government offices like the one in this lane.

The scheme is means-tested, taking into account income, savings and current home size, to target the poorest urban residents. That means people like Mr Chen, a chef, who, clutching his household documents in a brown envelope, has joined the queue here. He once worked in Australia as a driver but is back in Shanghai on a low income, living in a fifteen square metre room with his wife and daughter. “The room is very small and the house is very old,” he says. “We wanted to move out but we didn’t have enough money – so we’re hoping that this scheme can help us solve our situation.”

And he’s not the only one. Mounting anger at rising house prices has prompted the Chinese government to promise a massive expansion of affordable housing, with some ten million new subsidised homes to be built, in theory, this year alone – and a total of thirty-six million over the coming five years. This is a major reversal of policy: it’s little over a dozen years since China announced an end to welfare housing, which had been given, more or less free, to most urban residents by their employers. In an attempt to remove this “welfare burden” from enterprises, and make the Chinese economy more competitive, the government decreed in 1998 that most ordinary citizens would now have to rent or buy homes in the country’s fledgling commercial housing market, and it instructed state-run banks to help by providing mortgages.

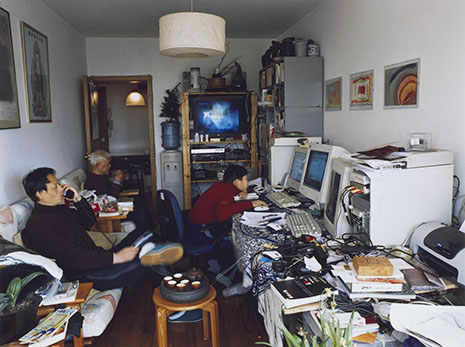

For those who did well out of China’s economic reforms, the opening up of the housing market offered startling new choices. The government encouraged local authorities to sell land to commercial real estate developers, who began building high-rise residential compounds and luxury suburban estates across the country. It led to a fascination with lifestyles and ways of living unprecedented in socialist China – the results of which have been entertainingly documented by Shanghai photographer Hu Yang, whose pictures of residents of the city in their homes (including the one above) have recently been on display at the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane.

For ordinary people, the blow was initially softened for many urban residents by a cut-price sell-off of state-enterprise housing to employees – rather like Margaret Thatcher’s sale of council housing in Britain in the 1980s. And many families were so excited at the prospect of new homes that several generations pooled resources to buy new apartments, even as prices began to rise.

But home ownership is out of reach for many. Prices in China’s major cities are now thirty or forty times the average family’s annual income, compared to eight or ten times in major western cities, according to leading sociologist Hu Xingdou. It’s become a vicious circle: while the central government has talked for years about cooling the property market, real estate has become one of the country’s biggest generators of revenue and employment. China’s biggest developer, Vanke, last year made profits of over US$1 billion on sales of $15.2 billion. Increasingly lucrative land sales to developers make up a significant part of many local government’s revenues; passed on to purchasers, the cost of land accounts for an estimated half the cost of each new home.

Even middle-class families are finding themselves priced out, as rich investors from other parts of China and abroad move in. Making it harder for speculators to obtain multiple mortgages; introducing a trial property tax; restricting purchases to one property per family in some cities – none of these measures seems to have significantly reined in prices (though they may have contributed to the rise in the cost of renting, as buying becomes more complicated). Soaring rents have meant that many young graduates working in white collar jobs in China’s cities have little choice but to live in tiny spaces in illegally subdivided shared rooms – known in Chinese as “ant colonies.”

The affordable housing policy – which includes both homes for sale at between one-fifth and one-third of market prices, and houses for rent at subsidised rates – is a major plank in the government’s efforts to convince its citizens that it can foster “inclusive growth” and greater equality. These are two of the main goals of the country’s next five-year economic plan, which comes into effect this year. Indeed, many analysts see it as an important part of attempts to shore up the government’s legitimacy, and burnish the legacy of President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, both of whom will stand down in the next two years, and who have set much store on bringing “social harmony.”

But can they make it work? The enthusiasm of many local governments and real estate developers for affordable housing has been questionable at best. Like the banks, they see the scheme eroding their profits. After authorities failed to reach last year’s target for affordable home construction, however, the Chinese government recently insisted that provincial governments sign a public pledge stating how much affordable housing they will build this year. And some property developers are beginning to express a willingness to participate.

But even a fully implemented scheme might not satisfy many of China’s poorer urban residents. Applicants in Shanghai’s Hongkou district grumbled that the new homes were in distant suburbs with few amenities. One middle-aged woman and her retired mother complained that even their single-room home was too big to qualify them for the first batch of subsidised housing. And Mr Chen looked a little glum after emerging from the neighbourhood office; he fulfilled the criteria, he said, but doubted he could pay the mortgage on even the cheapest affordable home, at 300,000 RMB (A$43,700). “If you’re poor enough to qualify for the scheme, you’re too poor to be able to afford it!” he lamented. China’s migrant workers, meanwhile, don’t qualify for the scheme at all.

The government is taking other measures to cool house prices, forcing developers to make bigger down-payments when they buy land, experimenting with a new property tax, and asking cities around the country to set targets for increases in real estate prices. But Beijing was the only city that pledged to seek a fall in prices in real terms; most others plumped for a 10–15 per cent increase, linked to GDP or income growth.

To cool the market effectively, a commentary in the official China Daily suggested, the government would need not only to build even more affordable housing but would also to turn off the flow of liquidity to real estate developers, which has fuelled rising prices. With China’s property industry now “the single most important sector in the entire global economy,” according to UBS economist Jonathan Anderson, that would require a great deal of political courage. The alternative, however, is continuing housing woes for many of the country’s citizens. •