The increasingly fractious politics of Covid-19 do more than expose the tensions at the core of Australian federalism. They highlight the variety of responses available for what is a severe security threat. Those who defend the premiers who have closed state borders — reportedly the great majority of constituents — see in their local leaders people committed to a robust defence of collective wellbeing. Their critics assert a counter-attachment to individual wellbeing, highlighting the ancillary costs, possibly crippling, of prolonged economic recession. Each side appeals to experts to back its case.

If only it were so simple. In Clive Palmer’s so-far-unsuccessful quest to demolish state borders we have seen a Federal Court judge compelled to adjudicate among a range of epidemiologists testifying to the effectiveness, or otherwise, of border closures in preventing virus spread. In the meantime, complaints (whether by Scott Morrison or Paul Keating) that the case for border closures is weak don’t mean much north of the Tweed, where Queensland has managed to keep community transmission close to zero.

Why is Australia like this? At the core of the federation compact is the immovable fact that the Constitution moved a specified range of powers from the states (then colonies) to the federal government. The list did not include responsibility for health, other than the limited scope allowed by the quarantine power, so the states were left with virtually sole power over health-related matters.

Famously, section 92 of the Constitution appeared to protect the notion of freedom of movement, or at least of “trade, commerce and intercourse.” The implied freedom of personal mobility didn’t stop the states imposing strict border controls in the severe pandemic of 1919, and the helplessness of the federal government in the face of obdurate state premiers was as evident then as in 2020.

But there was no equivalent in 1919 of a Clive Palmer challenging the border closures, and so no opportunity for the Commonwealth to contemplate whether it might join the case — or then withdraw from it, as has recently occurred. Perhaps that was a missed opportunity of 1919: at least the High Court might then have laid out the ground rules, as it might yet come to do. But which way would the court have gone anyway?

A few years earlier, in 1912, the High Court had tackled the question of cross-border mobility in a way that is often cited as revealing an implied doctrine of freedom of movement throughout the nation. The case (R v Smithers) originated in the conviction and imprisonment for twelve months of one John Benson as a prohibited immigrant into New South Wales. Benson had been convicted in Victoria of a vagrancy offence, and in 1903 New South Wales had passed a law to exclude convicted criminals.

The four judges of the High Court were unanimous in quashing Benson’s conviction while not invalidating the legislation. Some of the reasoning went to the seriousness of the harm likely to be caused by a person convicted merely of vagrancy. In the main, though, the judges focused on the need to protect the freedom of movement they found implied in section 92 of the Constitution. In so deciding, they were careful to deal with the possibility that there might be a constraint on freedom of movement in what they all referenced as the “police power” of the states. In the end, only Justice Isaacs was very confident that section 92 was an “absolute guarantee” of interstate freedom of transit and access.

What was this “police power”? The concept goes to the fundamental scope of government, which the Commonwealth’s constitutional handbook (Quick and Garran’s Annotated Constitution, published in 1901) explained by reference to American constitutional law. “The police powers of a State,” it declared, “were nothing more nor less than the powers of government inherent in every sovereignty to the extent of its dominions.”

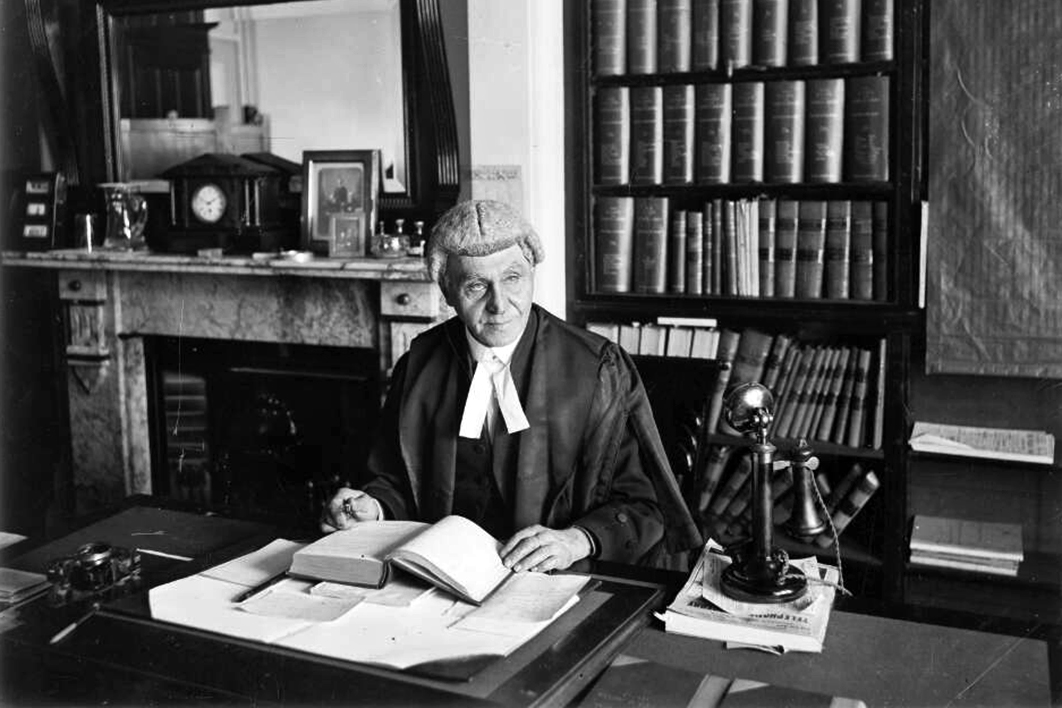

Arguing the case for New South Wales in 1912 was its attorney-general (later premier) W.A. Holman, throughout his career an ardent advocate of states’ rights. He argued that the Constitution had left to the states all those powers necessary to protect their citizens. This was the “police power,” a doctrine much deployed in US litigation over the rights of the states, referencing (as Justice Barton acknowledged) “the right of ‘self-defence’ in respect of such matters as internal order, or the safety, health and morals of the people of the State.”

The question, in Australia as in the United States, was whether such a power had been limited by the Constitution. Did the federating document constrain the power of individual states to control the entry of undesirable people, for whatever reason? Holman insisted that the states had such rights, by default, and challenged the judges to consider the risks of invalidating the exclusion law. Such a result would be disastrous, he said: “Even the quarantine powers of the State would be ultra vires. If a smallpox victim came through from Queensland to Sydney, and said he wished to go Melbourne he could not be prevented.”

Not even Isaacs, strongest in his dismissal of Holman’s argument, answered that point directly. The judge’s advocacy of freedom of movement was untrammelled, and the appeal of his reasoning remains admirable for its breadth of egalitarian concern. “If [a prohibited person] can be prevented for the sake of preserving the morals of the people,” he wrote, “then I am unable to see any limitation upon the power of the State to exclude whatever persons or property they choose to declare prejudicial to their people.” But unlike the other judges, Isaacs did not approach the difficult case, raised by Holman, of the possible necessity of restricting the movement of infected people in a pandemic.

Seven years later Holman again entered the fray on the question of a state’s right to close its borders. This time he was premier of New South Wales, and the controls were being exercised “in defence of the health of the citizens of this State.” Responding to the Spanish flu outbreak, the government had declared an emergency under the state’s health legislation, enabling closure of the borders, restrictions on assembly and commerce (first in the City of Sydney and later in the wider metropolis) and enforcement of mask-wearing on public transport.

Throughout February 1919 the NSW premier defended his state with an ardour that sometimes tested the patience of the Commonwealth. Compared with Queensland, whose Labor government took on the Commonwealth (indecisively) in the High Court over the scope of its quarantine powers, New South Wales was generally conciliatory. But with tension arising from the management of troops returning from war in the middle of a pandemic, the Constitution was brought into play unexpectedly in late February in one of those incidents that have fallen victim to historical amnesia.

On 25 February 1919, with quarantined soldiers growing increasingly restless, Holman cabled acting prime minister W.A. Watt calling on the federal government to protect the state from the danger of quarantined soldiers escaping their confinement and then being liable to arrest by local police. Holman’s request was made under section 119 of the Constitution, the provision that enables the Commonwealth to respond to a state’s need to protect itself against “domestic violence.” In doing so, he exposed a reality of the federation: the states had their own considerable “police powers” but had ceded to a national government the power to raise a defence force and use it, as a last resort, within the national borders.

In the event, a direction via the military’s Sydney commandant had the desired effect, the rebellious troops calmed down, and a rare call-out of military aid to the civil power was quickly concluded. So quickly, indeed, that when prime minister William McMahon was asked by opposition leader Gough Whitlam in 1971 about the previous use of section 119 powers, a search of the National Archives failed to include this among the few instances recorded.

When he called on the Commonwealth to defend his state from the threat of troops breaking quarantine in Sydney in 1919, Holman was acknowledging the limits of his state’s capacity to defend its borders. Barring major constitutional change in the arrangements underlying the federation, Australia seems destined to remain captive to this kind of politics. That may not be a wholly bad thing. Doing away with the freedom of states to determine local health priorities would not end the problem of determining what kind of unit of government would be a more effective instrument of pandemic control.

The much-vaunted solution of determining what constitutes a “hotspot” might limit the territorial reach of the virus. But it would not end the controversy over the criteria for applying controls over mobility or assembly. And, as the prime minister has repeatedly learned, there is little the Commonwealth can do in the face of the kind of emergency created by a pandemic. The politics that has justified the “stop the boats” approach to the national border has met its match in the “stop the virus” approach to state borders. •