When his brother Oscar died of a heart attack in early January 1969, Syd Negus began thinking about death — and taxes. Oscar had died at sixty-seven and another brother at sixty-four. “I said to myself, ‘By golly, Syd — you’re fifty-eight,’” the former building contractor told the Women’s Weekly. “‘On paper you’ve only got another nine years to live.’”

Or perhaps even less. Despite exuding “a bluff, hearty status quo solidity,” as the Weekly’s Lorraine Hickman wrote, Syd had been increasingly worried about his health. If he were to die, he feared that death duties would eventually leave his wife Olga uncomfortably short of funds. In fact, he calculated, 50 per cent of their assets would go to the state and federal governments.

Whether or not he got the figure right, his arithmetic led him to create an anti-tax campaign that would have a spectacular real-world impact. Within just over a decade, every Australian government, state and federal, had abolished death duties, making Australia one of just two Western countries that no longer taxed bequests or inheritances.

Negus’s success attracted the attention of Willard H. Pedrick, a professor of law at Arizona State University. With a research grant from the privately funded Lincoln Institute he came to Australia in 1980 to find out how and why Australia had gone it alone. Back in America he eventually published his findings in the Western Australian Law Review under the unlawyerly title, “Oh, to Die Down Under!”

As Pedrick described it, Negus’s campaign started small. He began by placing ads in local papers arguing that “bereaved and bewildered widows” were being “robbed of their just rights” by estate taxes, and inviting readers to sign a petition and donate to his campaign. The results, according to Pedrick, were “simply astounding.” Thousands of people signed the petition forms in the ads and posted them to Negus, many of them adding a cash contribution. “The Negus mail,” Pedrick wrote, “became a flood.”

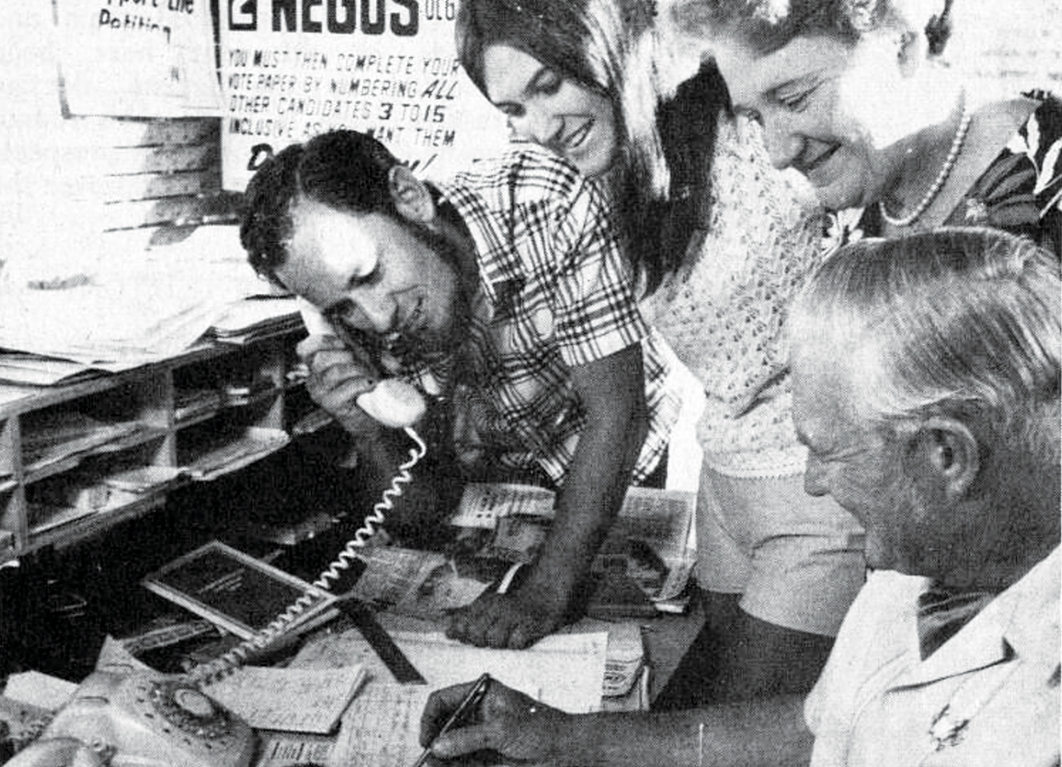

“We started off with our own phone and a few volunteers,” Negus told the Women’s Weekly. “Then we had to employ two full-time shorthand typists and two juniors, helped by about forty volunteers… We turned the sleep-out into our post office, ended up having to get three telephones and four extensions, and made the sunroom into an office. And I overflowed into the dining room.”

First in Perth, then further afield, Negus began addressing public meetings and appearing on radio and TV, displaying the “unflagging self-confidence, an almost abrasive assertiveness and the ability to talk quickly, constantly and at great length” that an Adelaide Advertiser journalist remarked on the following year. After he turned up uninvited to a meeting of the state’s farming organisation, he recalled, the meeting voted to donate $1000 to his campaign.

The opportunity to go national came with a Senate half-election scheduled for November 1970. Negus professed to be pessimistic about his chances of becoming Western Australia’s first-ever independent senator — “I was doing a lot of praying” — and told Ferrell he wasn’t able to outlay anything like what the major parties spent on campaign materials. Nor did he have much on-the-ground help on polling day: “I don’t suppose — when the time for the election came up — there would’ve been twelve polling booths throughout the West with people on it handing out how-to-vote cards for me.”

Watching from Sydney, though, the Bulletin’s Donald Horne thought “the poujadist from the west… will probably surprise us (and himself) by this week being elected one of Western Australia’s senators.” Horne was right: Negus beat the third candidate on Labor’s Senate ticket by 4000 votes and headed off to Canberra.

It turned out to be a frustrating few years for the surprised senator. He made virtually no headway with his campaign during the dying days of William McMahon’s Liberal government, and after Gough Whitlam became prime minister in 1972 he tried unsuccessfully to amend the Estate Duty Assessment Act and have the federal government subsidise the abolition of state probate duties. The latter proposal was supported by the Asprey inquiry into taxation, which reported in 1975, but wasn’t taken up by Whitlam or his successors.

But Negus’s focus on the impact of the taxes on widows eventually struck a chord. “With the Women’s Electoral Lobby adding their voice to the view that death duties were discriminatory to women,” wrote Ferrell, “Whitlam responded to the mounting pressure by promising that if Labor was re-elected, no widow or widower would be forced to sell the family home to meet death duties.”

Negus might have been surprised by WEL’s support. “Personally, I’m sorry to see these ladies talking about equality,” he told the Weekly. What did worry him was that women weren’t aware of the tax implications of their homes and other assets being held in their husband’s name, which was often the case.

Still, Whitlam’s promise was progress. Not only that: Negus had achieved one very important thing before his Senate career was cut short by the 1974 election. He had turned inheritance taxes into a national issue. And the apparent popularity of his campaign hadn’t gone unnoticed in at least one premier’s office.

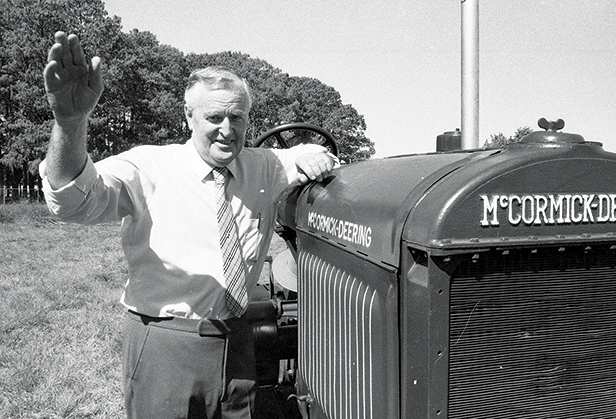

The premier in question was that shrewd rural populist Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who was part-way through his nineteen years at the helm in Queensland. Egged on by a series of Courier-Mail articles highlighting inequities in the estate duties levied by his own government, he announced in 1975 that spouses’ inheritances would no longer be taxed. Then, two years later, he declared the taxes’ complete abolition (much to the surprise, it emerged, of the state treasurer). It was a popular move in a state Pedrick described as a “hotbed of agrarian resentment.”

In the hope of attracting new residents and new spending, Bjelke-Petersen’s ministers — enthusiastically supported by the state’s tourism authority and business groups — set about promoting Queensland as a tax haven for retirees from the south. “Millions Could Flow North,” said the Bulletin’s headline. “Many observers,” Pedrick found three years later, “thought the abolition of death duties in Queensland was in fact a significant factor in a movement of capital to the Gold Coast state.”

Agrarian hotbed: Queensland premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen. Lakeview Images/Alamy

Were they right? Another American, economist Philip Grossman, painstakingly analysed the data during a visiting fellowship in Australia in 1989. Complicating his task were two other events that might have boosted Queensland’s population at around that time: the Whitlam government’s 25 per cent tariff cut in 1973, which sent some unemployed manufacturing workers northward from Victoria and South Australia, and emigration from the Northern Territory after Cyclone Tracy struck in December 1974.

Grossman took interstate migration figures compiled by Adelaide University geographer Graeme Hugo, ran them through an eye-glazingly complicated formula he explained at length in the journal Publius, and came to a clear conclusion: “Queensland’s population growth during the first three years after abolishing death duties was an average 0.20 per cent higher due to migrants avoiding the death duties of the other five states. On average, population growth in each of these states was 0.04 per cent lower as a result of the tax.”

Not earth-shattering perhaps, but perceptions were as important as facts. Worried that an exodus might be underway and anxious to head off tax-dominated elections, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia abolished taxes on estates left to a spouse. Western Australia and Tasmania followed in 1977, and the federal government dumped its inheritance tax altogether in 1979. Estates passing to children continued to attract duties in those five states until 1980 (in the case of South Australia and Western Australia), 1981 (in Victoria and New South Wales) and 1982 (in Tasmania).

And so Australia joined a very select group of Western countries — Canada was the only other member — that spared estates from taxation. New Zealand soon joined up, then Sweden, Austria and Norway. But every other comparable country — including Britain, France, Germany and even the United States — retained inheritance taxes, and still levies them (though often with very generous exemptions).

Syd Negus shouldn’t take all the credit, or the blame, for setting in motion the abolition of Australia’s estate taxes.

As Willard Pedrick discovered, the taxes’ “monumental defects” made them ripe for attack. Unusually, they were levied separately by both state and federal governments (the former raising about twice as much between them as the latter). The tougher state taxes, which in some cases cut in on estates worth as little as $20,000 (about $130,000 in today’s dollars), could mean a family home had to be sold to raise the necessary funds. Farmers and other small businesses with income-generating assets faced a particular problem finding the cash to pay the duties — and became another highly receptive constituency for efforts at abolition.

The taxes also had another big flaw: they could relatively easily be avoided by people with access to the right expertise. As a result, they fell more heavily on the middle-income households who came within their scope than on more well-heeled households.

Among the justifications for abolishing the taxes was the belief that wealth was distributed more equally in Australia than in other countries, making inheritance taxes unnecessary here. “There is a kind of folklore to the effect that the Australian society, if not egalitarian, is at least more egalitarian than other industrialised countries,” Pedrick wrote. “The myth is attractive,” he added, “but it does not conform to the facts.”

If the myth was off the mark in 1980, it’s unmistakably deceptive in 2021. In a recent report, Inheritance Taxation in OECD Countries, the OECD pointed out that the wealthiest 10 per cent of Australian households own 46 per cent of the country’s wealth — scarcely an egalitarian paradise. And, as John Quiggin showed recently in Inside Story and the OECD report confirms, that concentration of wealth will inevitably worsen — via inheritances.

The growing evidence that inequality this great is not just socially and politically damaging but also economically harmful has fuelled proposals to toughen up inheritance taxes, at least in countries that do have them. The latest expert support came in the OECD report, which argued that inheritance taxes could play a “particularly important role” following increases in inequality and falls in tax revenue fuelled by the pandemic. As the report shows, other countries have tended to react to complaints about inheritance taxes over the past half-century by limiting their reach rather than abolishing them altogether.

Here in Australia, support for a well-designed inheritance tax dates back decades. In the mid 1970s, in the midst of Negus’s campaign, a Senate committee backed state-level estate and gift duties, Treasury was arguing that estate duties were “important and basic in the system,” and the Asprey committee concluded they played “a quite essential role” in the tax structure as a whole.

Thirty-five years later, the final report of the Future Tax System Review (better known as the Henry review) concluded that “a tax on bequests would fit well with Australia’s demographic circumstances over the coming decades.” During the next twenty years, it went on, “the proportion of all household wealth held by older Australians is projected to increase substantially. Large asset accumulations will be passed on to a relatively small number of recipients.”

Those recipients aren’t only relatively few; they are also relatively old and relatively rich, according to an analysis of detailed probate data from Victoria released in 2019 by the Grattan Institute. “On current trends,” the institute’s Danielle Wood and Kate Griffiths write, “much of accumulated wealth in the hands of Baby Boomers will be handed down to the wealthiest Generation Xers, significantly exacerbating wealth inequality, and inequality of opportunity. Inheritances reinforce the advantages of having rich parents, such as better schooling, connections, and a greater ability to take risks because of a parental safety net.”

Inheritance tax rates, thresholds and exemptions vary enormously across the OECD. Intergenerational transfers of more than US$11 million are taxed in the United States, for example, whereas the threshold in Belgium is just US$17,000. “Most countries have progressive tax rates,” says the OECD, “but around one third apply flat tax rates, and tax rates differ widely.” Gift taxes are generally used to reduce pre-death tax avoidance.

An Australian inheritance tax would need to be not only as straightforward and hard to avoid as possible — the Henry report covered these issues in some detail — but also politically viable. (Labor’s complex franked dividend proposal in 2019 was an object lesson in how not to sell a tax change.) The recipient rather than the estate should be taxed, says the OECD, and the Grattan Institute argues that the funds raised should be directed — and be seen to be directed — to low- and middle-income households. Spouses would be exempt from the tax.

An inheritance tax should target the largest bequests. It should be set at a rate high enough to moderate the growth in inequality but low enough to undercut the inevitable opposition from people whose wealth gives them undue political influence.

Syd Negus’s campaign targeted an unfair and badly designed system of inheritance taxes. With the Australian Bureau of Statistics reporting that wealth inequality worsened by nearly 5 per cent between 2005–06 and 2017–18, the time is right for a well-designed inheritance tax system. •