Three down, one to go: antipodean elections in the age of Covid-19, all of them faced by sitting Labo(u)r governments (and, as it happens, in unicameral parliaments). Like all elections, many currents flowed under different circumstances, but it is reasonable to conclude from the results that Covid-19 is good for incumbents, at the moment anyway. It heightens that authority, that safe-option status, usually enjoyed by governments, particularly if they emphasise it, as all four have done.

It’s also a difficult time for oppositions, particularly the centre-right ones under internal pressure to adopt extreme positions (and estrange themselves from the electorate). In Victoria, the opposition’s woes seem to increase with what should be the Andrews government’s travails.

First off the rank, in August, was the Northern Territory’s Gunner government, returned with 54 per cent of the two-party-preferred vote. The other two elections — in New Zealand and the Australian Capital Territory — were in proportional representation systems, but if you guesstimate two-party-preferred from their primary results (as our pollsters routinely do after measuring first-preference support) you get about 60 per cent for NZ Labour and 55 per cent for ACT Labor. Next up, Annastacia Palaszczuk faces the voters this Saturday.

I’ll devote more space to Queensland later this week, but here I’d like to draw your attention to another dynamic currently favouring Labor at state elections.

Recall two dramatic Queensland elections: the humungous swing to the Liberal National Party in 2012 and an almost identical one the other way three years later. Did something happen in the intervening years? Yes, there was a change of federal government.

Federal governments matter at state (and territory) elections. A lot. In power nationally, party X drags down the support of its second-tier counterparts.

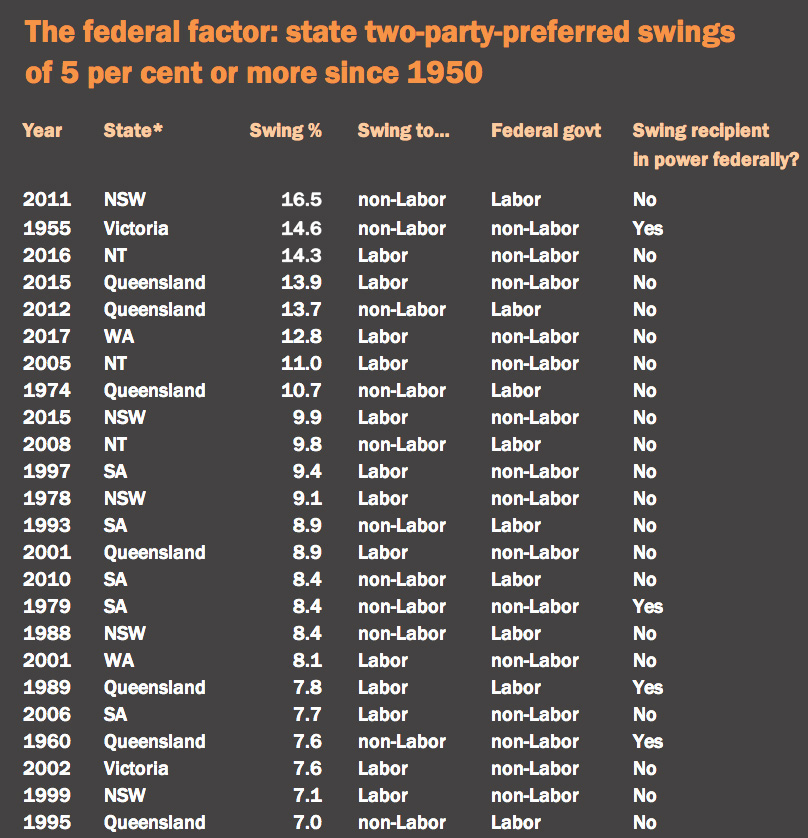

This table — state two-party-preferred swings of 5 per cent or more over the past seventy years — illustrates the point dramatically. Nearly all the big swings, either way, are against the party in office nationally. (The stand-out exception, in the number two slot, Victoria in 1955, immediately followed the Labor Party split.)

* Includes Northern Territory after 1980. Sources: Electoral commissions, Psephos, David Barry, Wikipedia. Most figures before the early 1980s are estimates.

The trend is clear in the average numbers as well. In the thirty-nine state elections under a federal Labor government, the average two-party-preferred result is non-Labor 53.3 per cent (whether it’s Liberal, Country Liberal Party, LNP or Liberal and National) to Labor 46.7. And the eighty-seven that took place when the conservatives were in office in Canberra average to Labor 50.2 per cent and Coalition 49.8. In swing terms, the mean under federal Labor is 3.5 per cent to the Coalition; under federal Coalition it’s 2.0 to Labor.

It’s not as if these voters consciously decide to balance things out. They don’t say, “I’m voting for X because Y is in Canberra.” It’s just one of those things. And the federal government doesn’t have to be toxic at the time, although it helps. From the late 1990s until 2007, state Labor parties thrived, clocking up record majorities in some places, during both good and bad times for the Howard government.

So it’s difficult for a state/territory party to move from opposition to government in these circumstances. They start behind the eight ball. But it can happen, and did most recently in South Australia in 2018 and Tasmania in 2014. Before that, though, you need to go back to New South Wales in 1995. •