Halfway through the third volume of Frank Moorhouse’s epic trilogy centred on the fictional Edith Campbell Berry, a young Australian woman who travelled to Geneva to join the League of Nations in the 1920s, I was startled by a scene in which Edith and her brother visit their parents’ graves to hear a memorial eulogy about their mother’s early life. The middle-aged Edith is back in Australia working in Canberra.

Some parts of the eulogy seemed familiar to me, including the observation that “Cecilia Gladys Thomas,” who had studied singing with “a Mrs Trantham Fryer,” had a fine contralto voice and started a poultry farm at Deepdene to pay for her training. A page or so further on, we learn that Cecilia, after her marriage to Peter Berry, became “a passionate friend of Vida Goldstein” during the Great War and created the Women’s Peace Army with her. The penny dropped. I had researched the suffragist women in Goldstein’s WPA for my doctorate and I knew who her passionate friend was.

Moorhouse’s acknowledgements for the third volume, Cold Light, explain that “the orations for Edith’s mother and family are a collage drawn from the lives of actual contemporaries, as recorded in The Australian Dictionary of Biography.” It amused me to find that the extraordinary life of Cecilia Annie John — the Deepdene poultry farmer — had caught the eye of Moorhouse, who immortalised her as Edith Campbell Berry’s mother.

Outside Moorhouse’s portrayal, Cecilia John is little remembered in Australia, except as a real-life character in books about Goldstein, most recently Jacqueline Kent’s new biography, Vida: A Woman for Our Time. Unlike her fictional counterpart, she was not married when she became Goldstein’s confidant; in fact, her life took quite a different trajectory.

Cecilia John was born in Hobart in 1877 to Welsh blacksmith Daniel John and his wife Rosetta. Even though she may have inherited her fine singing voice from her Welsh forbears, she clashed with her father from an early age. Her desire for a musical career made her determined to leave Tasmania for the mainland in the 1890s, where her goal was to train with singing teacher Charlotte Tranthim-Fryer. To pay for her training, she did indeed set up a poultry farm in what was then the outer suburb of Deepdene, building the sheds herself from scrap timber.

Cecilia may have started lessons with Charlotte Tranthim-Fryer when she was teaching in Hobart in 1895; if so, her training there would have been short-lived but seems to have been enough to fuel her passion. Tranthim-Fryer left for London in 1896, where she attended the Royal Academy of Music and her artist husband, James, studied sculpture. After the couple returned to Australia around 1900, Charlotte resumed her career as a singing teacher, this time in Melbourne. James became the first director of the Swinburne Technical College in 1908 and head of its art school nine years later.

Cecilia was soon studying with Tranthim-Fryer, and by December 1902 the magazine Table Talk was announcing her public debut at a Melbourne Liedertafel concert. Among other pieces, she sang Brahms’s “Sapphic Ode,” with one reviewer describing her as possessing a “voice of good mezzo-contralto quality” and showing “evidence of good feeling and an artistic temperament.” Three years later, in a review of a concert in Sydney’s Albert Hall by the Melbourne Concert Party, she was described as a contralto with “a fine powerful voice.”

Photos of the members of the Musical Society of Victoria featured in the Melbourne Weekly Times of 20 May 1905. A head-and-shoulders shot of Cecilia John shows a young woman with an aloof gaze, her dark hair wrestled into an elaborate Edwardian coiffure. Above a low-cut evening gown, a string of pearls encircles her neck.

Having become a registered music teacher and taken on singing and voice production students at a studio in Collins Street, Cecilia’s other talents began to be evident. In late 1912 she was approached to join Vida Goldstein’s Women’s Political Association by a young woman who lived near her poultry farm in Deepdene. Doris Hordern, Vida’s joint campaign secretary for her bid to win the seat of Kooyong, had been taunted by her anti-suffragist father to sign up as a WPA member “that woman in trousers” who lived down the road.

Cecilia burst onto the WPA scene in 1913, becoming Goldstein’s close confidant and rapidly rising to the position of business manager. Goldstein was forty-four years old and had been working for the women’s cause since before the turn of the century. She was clearly swept away, if not enamoured, by the energy of this younger, multi-talented woman who wholeheartedly supported her suffragette militancy.

In the event, Vida lost that 1913 election to Liberal candidate Sir Robert Best, but her creditable showing convincing her to continue seeking a federal seat. She would make a further three unsuccessful bids, the last in 1917.

Cecilia’s swift rise through the ranks of the WPA didn’t go unnoticed among other hard-working members. “When Miss John wants a thing there does not seem anything to do but cave in,” one of them was heard to grumble. The elegant and equable Goldstein was revered by her acolytes in the WPA, so jealousy of Cecilia’s sudden power over their president was perhaps to be expected. “Miss John’s” brusque and uncompromising manner didn’t help, but it seems Vida did little to quell the rumblings.

Some had good reason to feel aggrieved. Life had changed dramatically for Doris Hordern when Vida’s sister, Elsie Champion, sacked her from her job at the Book Lover’s Library after she became engaged to barrister and fellow WPA member Maurice Blackburn. Unhappily relegated to Deepdene, Doris could no longer pop in to the WPA clubrooms. But Maurice, who did often lunch or dine there, kept her informed about the situation.

Blackburn, too, had reason to feel aggrieved, having found that any opinion contrary to the WPA’s official line was no longer well received. After making a comment about the right of an expatriate anti-suffragist to write in the Argus that there was no women’s movement in Australia, he reported to Doris that “Miss John wants to hold a class at Deepdene for the education of me — what do you think of that, Mouse?”

What was making some of the WPA women, and at least one man, uncomfortable was not simply jealousy about Vida and Cecilia’s closeness or misgivings about the WPA’s increasing “sex antagonism.” Lurking beneath their criticisms of Cecilia John was the spectre of what was then regarded as perversion.

Maurice Blackburn dealt with the unease by recounting condescendingly humorous anecdotes to his fiancée. While Doris appears not to have responded in kind, it was clearly a shared topic of conversation. Relating an incident at the WPA club in late 1913, during which several of the members were complaining to him about “Miss John’s” ubiquitous presence, he finished with “Miss Goldstein and Miss John” coming in “almost arm-in-arm.” A few weeks later he told Doris, “Miss Kerr says that the latest about the engaged couple is that Miss John has given Miss Goldstein a gold watch. I said I thought a ring was the regular thing.”

Goldstein’s second campaign for Kooyong was played out against international tumult. After Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, the Australian government promised troops and warships to support its ally. Vida’s pacifism seemed out of place in this fervid atmosphere, and she polled fewer votes than she had the previous year. But she and her allies in the WPA were already turning their attention to the fight for peace.

The WPA’s members were far from united on the question. A resolution for the association to add opposition to compulsory military training and militarism to its platform produced a split, with a number of members — including the newly married Blackburns — tendering their resignations. Undeterred, Goldstein formed the Women’s Peace Army in July 1915, which would be totally devoted to peace propaganda. Cecilia John and Adela Pankhurst, recently arrived from London, set up branches in Sydney and Brisbane. The indefatigable Cecilia also formed the Children’s Peace Army.

After the WPA bought fourteen acres of land at bayside Mordialloc in 1915, Cecilia was closely involved in running a new women’s farm, providing expertise in raising poultry. The farm produced white leghorns, reared cattle and grew produce to be sold at the WPA rooms; landscape architect Ina Higgins supervised the growing of flowers and vegetables. Women and girls were employed and trained on the farm, about six at a time, throughout the war. A reporter from the Socialist was quoted in the WPA newspaper Woman Voter as saying that “the robust and ladylike girls… looked as intelligent and as healthful as it was possible to imagine.”

Throughout the war years Cecilia performed the banned anti-conscription song “I Didn’t Raise My Son to Be a Soldier” in her powerful contralto voice at rallies in Melbourne’s Guild Hall and on the Yarra bank. She was arrested on one occasion, spending the night in the City Watch House; on another, she turned a fire hose on a soldier who tried to grab the WPA flag from her.

An image of Cecilia John as chief marshal in the spectacular Women’s No-Conscription Demonstration and Procession of October 1916 remains vivid, even though there is no photograph of the event. A striking figure on horseback, she was reported to have been dressed in white and carrying a staff decorated in the purple, white and green colours of the WPA. Three young girls carrying banners led the procession; Cecilia, in turn, was followed by the members of the Women’s No-Conscription Committee, including Goldstein.

The procession from Guild Hall to the Yarra bank included eight horse-drawn lorries with tableaux, decorated lorries full of children, and many individuals on foot and in vehicles. At one point several dozen doves were released from the children’s lorries. As a letter in Woman Voter three years later, signed by “Merle,” recalled, “I never pass by the Public Library and see that wonderful woman-figure on her warhorse, but I think of Miss John, how all through the war she was the Joan of Arc amongst us.”

Cecilia resigned from the WPA in 1918 to devote more time to music. Later that year she set up the People’s Conservatorium with composer and pianist Annie Macky, aiming to bring “the world of art to the masses.” But she was back at work for the WPA in the following year after she and Goldstein were nominated to represent it and the Women’s Peace Army at the International Women’s Peace Conference in postwar Paris. After an adventurous trip involving several delays, they arrived to find the conference venue had been changed from Paris to Zurich, in neutral Switzerland, to where they quickly proceeded. As the Westralian Worker commented on 18 July 1919:

Miss Cecilia John, who has been speaking in Switzerland on behalf of Australia, adds to her accomplishments that of practical poultry-farming, music teaching, motor-driving, and platform oratory… She is of robust physique and personality, and a decided contrast to Miss Vida Goldstein, who is also abroad. The two clever women should be able to demonstrate overseas that the sex in Australia is as diverse as it is adaptable.

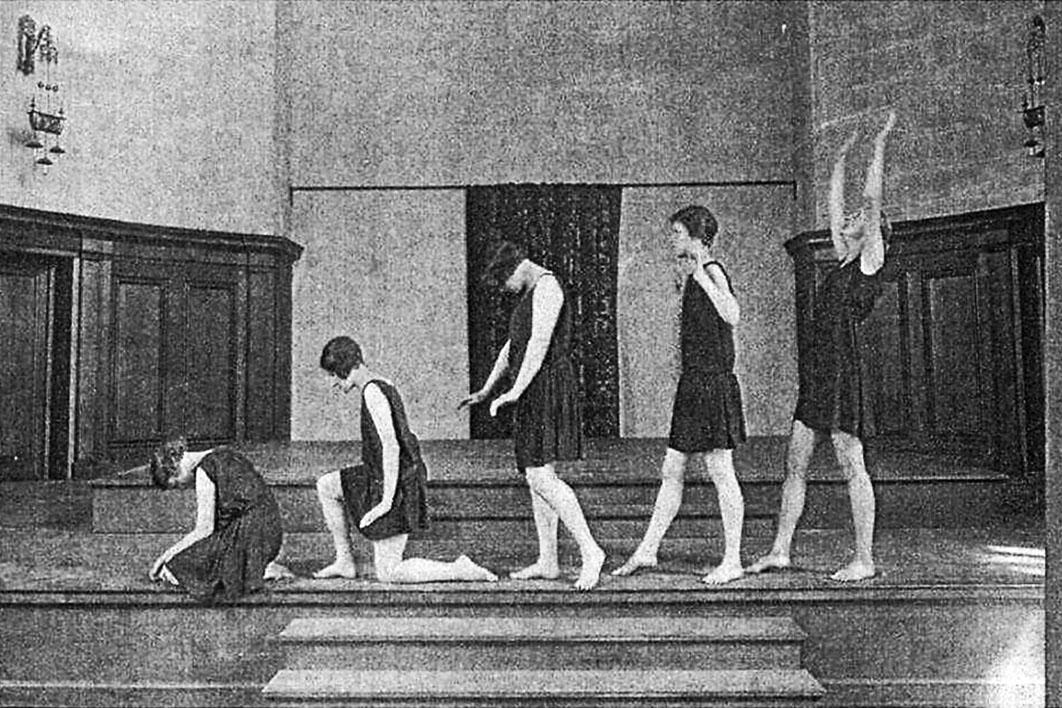

The visit to Switzerland would change Cecilia’s life direction entirely. In Geneva she became interested in Dalcroze Eurhythmics, a new method of teaching music through movement, when the movement’s founder, Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, presented his first international summer course since the war. Concerned about the postwar plight of refugees, particularly children, she also became involved in the Swiss Red Cross.

Parting from Vida Goldstein in England later that year, Cecilia returned to Australia to become the organising secretary of the Australian branch of the new Save the Children Fund. She left again for England in 1921 to pursue Dalcroze studies, and later also worked as overseas delegate at the London headquarters of Save the Children.

After attending the Dalcroze Summer School in Oxford in August 1921, she took a term of classes at the London School of Dalcroze Eurhythmics. Then, at forty-four, she joined the full-time training course, lowering her birth date by ten years on the enrolment form. Dalcroze appears to have provided Cecilia with an avenue for bringing together her passion for music and her interest in children’s education. From the start, and while still a student, she was also able to use her organisational and administrative capabilities to further the development of the school.

Cecilia and renowned Dalcroze teacher Ethel Driver became inseparable companions in the 1920s, eventually sharing a flat in London and a holiday cottage in Surrey. In 1923–24 they made a six-month tour of Australia, largely organised by Cecilia, for the London School, promoting Dalcroze in public demonstrations. With another graduate, Heather Gell, Cecilia and Driver gave demonstrations in schools and public halls in most states, involving selected children in the performances.

The tour attracted extensive newspaper coverage. Cecilia John was described as an “old friend, feminist, politician, singer and entrepreneur but now an exponent of the Music of Motion” in Melbourne Punch in January 1924. Promotional photographs taken in England were distributed to the press, and several featured with the articles.

In 1930, following the death of the founding director of the London School, Cecilia was appointed as warden and then, in 1932, as its principal. After the school’s premises in Fitzroy Square were bombed during the war, Cecilia and the committee organised its move to Kibblestone Hall in Staffordshire for the duration. In 1946, she was again instrumental in setting up the school’s new headquarters at Milland House in Liphook, Hampshire, where she remained principal until her death in 1955.

Cecilia John and Ethel Driver’s relationship lasted until Cecilia’s death. Ethel inherited her estate and died in 1963. Both women are buried in the same grave in the churchyard in Liphook.

As Cecilia John left no personal papers, any account of her extraordinary life must depend on external sources, formal and informal, including the gossip that surrounded her throughout. Today she would no doubt be part of the LGBTQI community, a positive discourse not available to her then. One disparaging comment repeated about her — that she had a “constitutional inability to compromise” — could be reconstrued as a strength; she certainly seems to have conducted her life on her own terms. •

This article draws on Patricia Gowland’s entry, “Cecilia Annie John,” in the Australian Dictionary of Biography; Joan Pope’s article, “Cecilia John: An Australian Heads the London School of Dalcroze Eurhythmics, 1932–1955,” in the Australian Journal of Music Education; and Carolyn Rasmussen’s book, The Blackburns.

My thanks to Joan Pope for generously sharing her research with me and for giving permission to reproduce the photograph above, and to Carolyn Rasmussen for giving me access to the Blackburns’ courtship letters, SLV MS11749.