Mayor Pete Buttigieg had been onstage for only a few minutes last Monday before it was obvious why he was destined to win the Iowa caucuses. I was seeing him in person for the first time, and like most of the 500-strong audience I was swept along by his powerful imagery and confident delivery. The contrast with Joe Biden’s caucus-eve speech, later that day, couldn’t have been greater.

I’m in Iowa as part of a tour of the early primaries led by Nicholas Wood, a former New York Times journalist who runs an organisation called Political Tours. Iowa is the first stop in the six-month race to determine who will face off against Donald Trump in November.

Buttigieg, a thirty-eight-year-old political prodigy, was strikingly impressive. This former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, comes from the American heartland — the same heartland that eschewed the insider politics represented by Hillary Clinton in 2016. Before a large crowd, he spoke with the air of a once-in-a-generation politician, his language and poise creating an Obama-like energy. His rhetoric is powerful and he delivers it all, during a long speech, without notes.

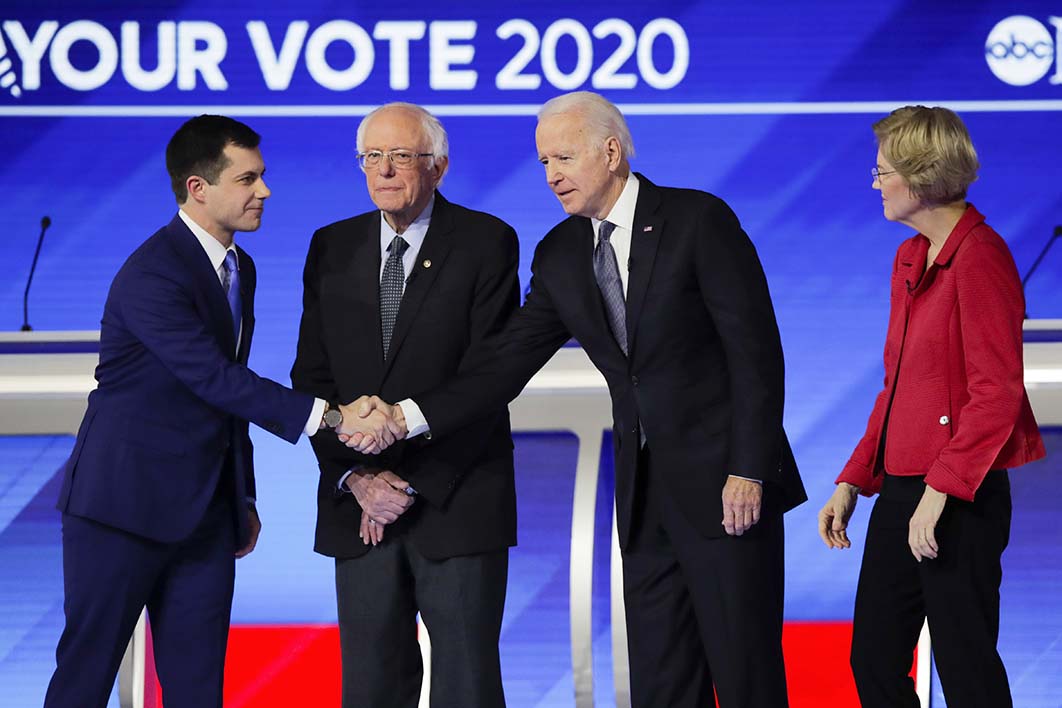

In interviews, Buttigieg exudes a gravitas that is unusual in someone so young. Despite his lack of experience in public office, his characteristics and experience would normally add up to a strong resumé for someone running for president. He is a war veteran, a person of faith and a former management consultant. In debate against his more experienced opponents, he not only confidently articulates moderate policy positions but has also successfully weaponised them, particularly against Elizabeth Warren, whose campaign faltered towards the end of last year over claims that her healthcare policy would be exorbitantly expensive and politically unsustainable.

While his rhetoric is powerful and he can hold his audience, his delivery can be slightly wooden or overly crafted. He doesn’t have the enchanting, lilting cadence that Bill Clinton used to win his party’s nomination or the timing Obama used to break from the pack.

Although Buttigieg seems destined to achieve remarkable things in public life, he has other problems in this race, too — particularly his inability to gain traction within the African-American community, which has become part of the narrative shadowing his campaign. He can’t win the Democratic nomination without lifting his support among these voters.

In a focus group run by an Iowa-based consulting firm, Essman Research, an African-American participant was asked about Buttigieg’s challenge with voters of colour. “He’s just another young privileged white guy,” the man responded. Buttigieg’s campaign has attempted to deal with this lack of support, but so far without success. Some of its efforts have been criticised as tokenistic, and it’s true that the campaign’s strategy sometimes seems crude and injudicious.

At the conclusion of his speech last Monday, for instance, Buttigieg was flanked by his partner and a group of politicians and community leaders, some of them African-American. Also on stage was a striking African-American woman wearing a “Ms Black America” sash across her chest. Buttigieg has also drawn sharp criticism for his failure to tackle systemic racism within South Bend’s police force. Tensions boiled over last summer when an African-American man was shot by a white police officer.

As a married gay man, Buttigieg’s sexual orientation is also seen as a political problem — and one that compounds his difficulty with African Americans. At a talk a few days before the primaries, well-known Iowan journalist David Yepsen, who has covered the primaries since 1976, argued that Buttigieg will “struggle to gain the support of older African Americans” because these voters are “older and more socially and religiously conservative.” Jepson compared Buttigieg’s challenge with the obstacles Obama faced in attracting white voters in 2008 and, further back, the need for John F. Kennedy, a Catholic, to win over Protestant voters in 1960.

Jepson isn’t surprised by Buttigieg’s showing in Iowa, a state that is more than 90 per cent white, but notes that “black voters are a key pillar in the Democratic electorate, and if he can’t win a big vote from them, he and the Democrats can’t win.” In the lead-up to the 1960 election, he says, Kennedy confronted the issue head-on in an important speech to Protestant ministers in Houston, Texas.

Biden’s rally, on the other hand, left me worried — very worried. For the first time during the caucus period, he drew a sizeable crowd, which was obviously a good sign for his campaign. But I was struck by how low-energy the whole event was: the lack of enthusiasm was palpable. I sat next to a woman who told me she had been a state senator for Maryland and had endorsed Bloomberg two weeks earlier. Why she was there, I’m not sure, but she must have sensed my lukewarm response to Biden’s speech; not unkindly, she observed that “it’s hard to clap when you’re not enthusiastic.”

Biden seemed diminished. His charm and aura of folksy decency are still there, but the intellectual agility he displayed when he demolished Sarah Palin and Paul Ryan in the vice-presidential debates in 2008 and 2012 seems to have gone. When he entered the hall, it felt like being at a ninetieth birthday party. Biden seems like an old seventy-seven, in sharp contrast to the seventy-eight-year-old Bernie Sanders and seventy-seven-year-old Mike Bloomberg, both of whom look sharp and vigorous.

Foremost in most minds has been “electability,” the question of which candidate can beat Donald Trump. Many Democrats, some grudgingly, have declared that Biden is the best bet. They point to polling match-ups between him and Trump in swing states, which Biden has almost invariably led, sometimes by big margins compared with his competitors.

In a large field of candidates, only time will tell if this polling is driven more by name recognition and Biden’s stature as vice-president than by his ultimate strength against Trump. If his performance at the rally is anything to go by, any lead he has over Trump in these polls could be illusory, and a brutal election cycle would end with his defeat.

Biden is a classic Washington insider. His supporters believe that a centrist with incrementalist positions is what the country is calling for, and that their candidate (rather than the best known of the other centrists, Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar) is the antidote to the exhaustion created by four years of Trump. As Mike Drake, the owner of a store that sells political memorabilia and ironically emblazoned t-shirts in the Iowa capital, Des Moines, describes the choice between Sanders and Biden: “Sanders is about replacing one grumpy old white guy from the right with a grumpy old white guy from the left” whereas a Biden presidency would please neither the left nor the right but would cheerfully offer America a rest from the exhaustion of four years of Trump.

So, is Biden really the best bet? History suggests otherwise. Neither Kennedy in 1960, Jimmy Carter in 1976 nor Bill Clinton in 1992 were considered safe candidates in the years they won the Democratic nomination. And Hillary Clinton was considered the safe candidate in 2016.

This hasn’t stopped the Republicans worrying about Biden, even to the extent that a Republican senator from Florida paid for ads in the lead-up to the primary painting Biden as corrupt. Biden responded to the attack during his caucus-eve rally, but not with any power or fluency.

If Biden can revive his flagging campaign and win the nomination, he will need to show intellectual agility in the head-to-head encounters with Trump, ruthlessly dragging the debates back to Trump’s corruption and unfitness for office. This quality was missing at the rally. At one point, someone heckled him about fossil fuels. Instead of dealing with the person directly, he said, “Don’t worry about him, folks,” a response that seemed patently inadequate.

Caucus night’s disastrous technical problems left the major candidates to respond initially to the vote on the basis of information gleaned from their supporters from precincts across the state. Biden’s body language suggested that he’d had a bad night, but the depth wasn’t obvious until the following day. For a politician of his experience, Biden’s attempt to spin his fourth placing — behind Sanders’s main opponent on the left, Elizabeth Warren — seemed surprisingly inadequate.

Perhaps more striking, once again, was his lack of fluency. Sentence by sentence, he looked down at his notes and then up again at the crowd: “This is a battle for the soul of America,” “We cannot let Trump win again,” “Character is on the ballot.”

The Biden/Buttigieg contrast says something deeper about America. Traditional faultlines are breaking down, and the country is looking for something new and fresh, but people, particularly Democrat voters, are unsure what that is. A particular divide is between rural and urban America: country towns are in sharp decline with people leaving for jobs in the American metropolis; farm bankruptcies are at an all-time high and suicide rates are growing; three-quarters of farm income is produced by a quarter of farming businesses. More generally, manufacturing has been in decline for decades, devastating both rural areas and cities.

On Monday, before caucus night, I talked with an older Republican voter who was once formally registered with the party. He expressed concerns about the direction of the country under Trump. Months ago, he registered as a Democrat for the first time and said that he would “caucus for Mayor Pete.”

Signs suggest that Buttigieg might also attract members of a group that political analysts call “the Obama–Trump voter”: those who voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012 but deserted the Democrats for Trump in 2016. In Iowa, he did well in the rural counties that are home to many Obama–Trump voters. For his part, second-place-getter Bernie Sanders appeared to attract significant support among white working-class voters. Biden, on the other hand, failed to garner winning support in any part of the state, and in some areas his vote was below 15 per cent.

Already the campaign has moved to New Hampshire. The race remains fluid, with the field yet to be substantially winnowed, but polls suggest that it is essentially down to five candidates: Sanders, Buttigieg, Warren and Biden, together with Michael Bloomberg, who has already spent over US$200 million but won’t enter the race until Super Tuesday in early March.

Despite Buttigieg’s surprise win in Iowa, Bernie Sanders is resurgent nationally and widely expected to win the nomination, a belief that will only be amplified if he wins New Hampshire. But commentators and centrist Democrats worry that he is unelectable. For David Yepsen, “the Democrats are facing a crushing defeat in November” if Sanders is the nominee.

Elizabeth Warren finished third in Iowa, but Nate Silver from FiveThirtyEight believes she exceeded expectations in the state and remains a viable contender, albeit less so than in the second half of last year. Some argue that her best shot now is to present herself as a unifying candidate who can bridge the fissures in the party between left and right. She is, after all, a Democrat, unlike Sanders.

For Biden, a bad result in New Hampshire will be catastrophic. Buttigieg leaves Iowa on a wave, with his figures improving with each new poll in New Hampshire. But his performance in Iowa also made him the biggest target in yesterday’s Democratic candidate debate in New Hampshire, and he still faces daunting challenges, particularly in states where the voting population better reflects the diversity of the Democratic base by being more racially mixed and younger, neither of which seems to benefit Buttigieg, in the polling at least. •