Alison Bechdel is famous for inventing the “Bechdel Test,” a sarcastic way of assessing whether a film is non-sexist — it must contain at least one scene in which two named women are shown together talking about something other than a man. A friend points out the aphorism embodies Bechdel’s essential method: the yoking together of the brutal and the wry, the serious and the comic. Beyond that, her reputation rests on Dykes to Watch Out For, a comic chronicle of lesbian life aimed principally, if not exclusively, at a lesbian readership. She has done much more, though, and what follows is the attempt of a straight male reader to bring himself up to speed.

Dykes to Watch Out For, a widely syndicated strip cartoon series, ran from 1983 to 2008, ending only after Bechdel achieved success with her first graphic memoir, Fun Home: A Family Tragic Comedy, later made into a Broadway play. Fun Home was followed by Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama (2013), then The Secret to Superhuman Strength (2021) and now Spent: A Comic Novel (2025). All these, leavened by a dry, mocking wit guaranteed to detonate outbursts of laughter throughout, retained the loyalty of her early readership while aiming to bring in a more broadly based following.

Leaving gender issues aside for the moment, Bechdel’s success depends on her breathtaking skill as an artist. She gets maximum effect from the extraordinary flexibility of the graphic narrative form. As a speciality, she makes a point of drawing not just people, or settings, but texts of all kinds: text messages, typed or handwritten letters, words on a computer screen, and pages of print from books, including pages from her own books.

I was struck by two pictorial conventions she uses to convey a character’s state of mind — the drawing of a face in profile with the mouth yanked around onto the presenting cheek so its expression is visible and readable, and the depiction of two- or even three-headed characters to capture a lightening transition from the expected to the unexpected. Particularly noteworthy is her attention to hands and hand gestures.

It is a paradoxical tribute to Bechdel that as one reads on, all these conventions, the pictorial ground of the text, tend to fade away, become transparent, not noticed, as one is drawn into the story being told.

Each of these books is so many-faceted that it is hard to know where to begin. One way in is via the use Bechdel makes of extensive reading. Fun Home, about childhood and coming of age, refers throughout to James Joyce’s Ulysses. The book’s central character, a sort-of Leopold Bloom to Bechdel’s sort-of Stephen Daedalus, is her talented, practical, polymathic, domineering father, a compulsive preceptor and DIY expert, who along with much else runs the family funeral home, the “fun home” of the title, part-time. He discovers in mid-life that he is gay, and finally, possibly, takes his own life. There are passing references to both Proust and Wilde, but the Icarus myth is central: Bechdel’s paradoxical fall to earth, the ultimate via negativa, is the discovery of her own sexuality.

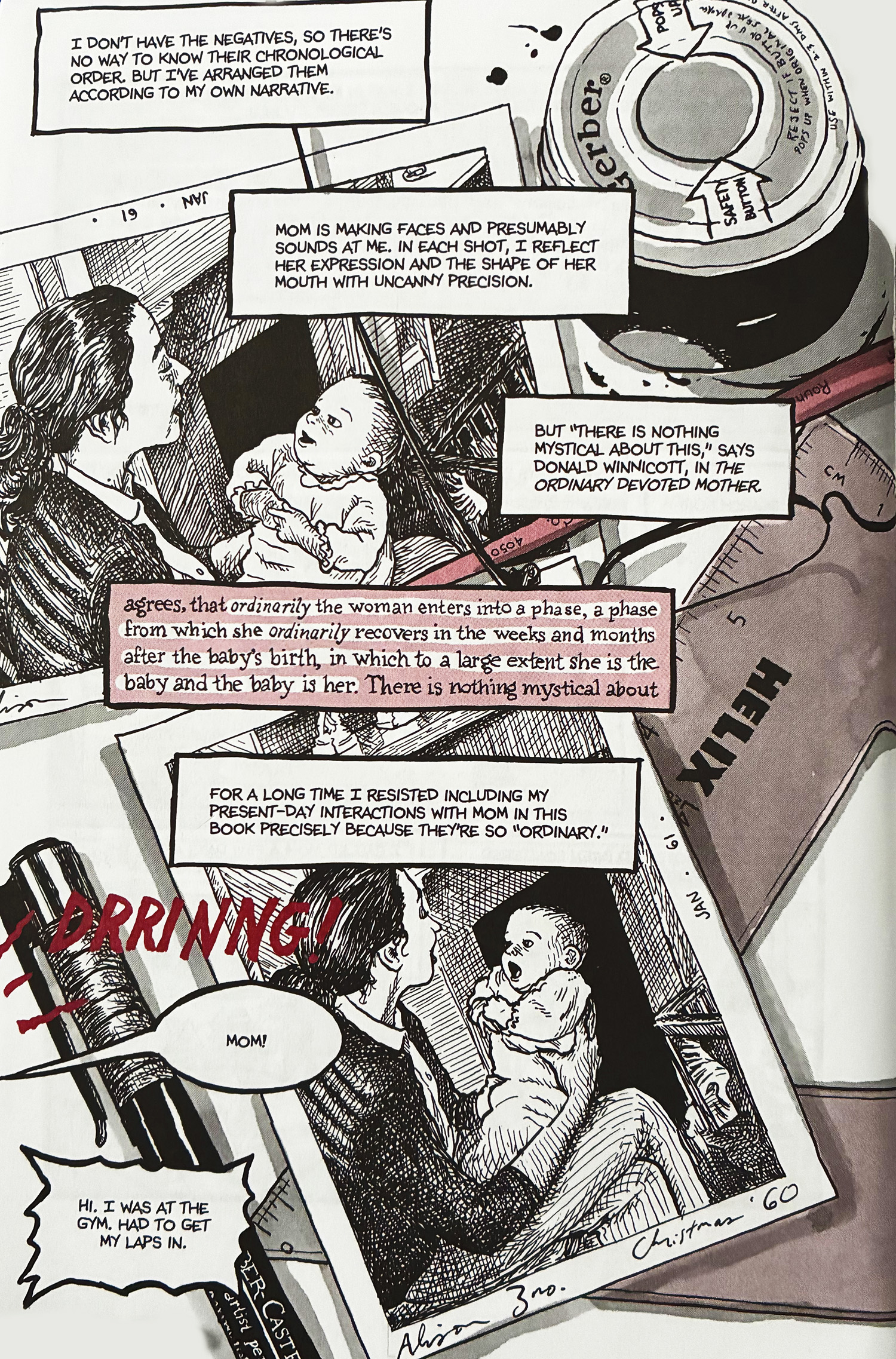

Are You My Mother?, although subtitled “a comic drama,” is in fact a sombre work about Bechdel’s fraught relations with her mother. For guidance she turns to the object relations psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. In one bravura double-page, Bechdel reproduces, by drawing, a sequence of mother and child photographs scattered across her worktable that, put together, rehearse her own fractured Winnicottian babyhood moment. In four steps the baby registers and then absorbs the gaze of an adoring mother eventually returning a look of pure delight until, in the fifth, and last, photograph, “the moment is shattered as I notice the man with the camera” — the interloper, her father.

Bechdel meets Winnicott, from Are You My Mother?

The scene is overlaid with several layers of print information in four text boxes of various shapes and outlines that act as a filter of multiple levels of information. A standard rectangular text box gives Bechdel’s establishing explanation of what the photographs are of and the problem of organisation they present (“I don’t have the negatives, so there’s no way to know their chronological order”). A second standard speech bubble shows Alison’s opening salutation in a phone call she makes to her mother (“Mom!”). In a third text box, this time with jagged outlines to indicate “phone conversation,” the mother replies with irrelevant banalities (“Hi. I was at the gym… couldn’t believe Lady Gaga on the Grammy’s last night… Puh-lease…. Those thighs…”). Then, in a prime example of the kind of authority Bechdel accords to Winnicott, there is a text box in half-tone in which Bechdel draws a highlighted extract of text from Winnicott’s essay “The Ordinary Mother and Her Baby” (“Ordinarily the woman enters into a phase from which she ordinarily recovers in the week and months after the baby’s birth, in which… she is the baby and the baby is her…”).

It is a great drawing, but as the Winnicott extract might suggest, object relations theory can be heavy-going, and it does drag down the book more than a little, not always producing clarifying insight. Bechdel varies the effect by drawing interesting scenes from Winnicott’s life. Are You My Mother? ends with another via negativa: “There was a certain thing I did not get from my mother… there is a lack, a gap, a void… but in its place she [gave] me something else… a way out.” The drawing shows the child about to stand on her own two feet, ready to walk out of frame.

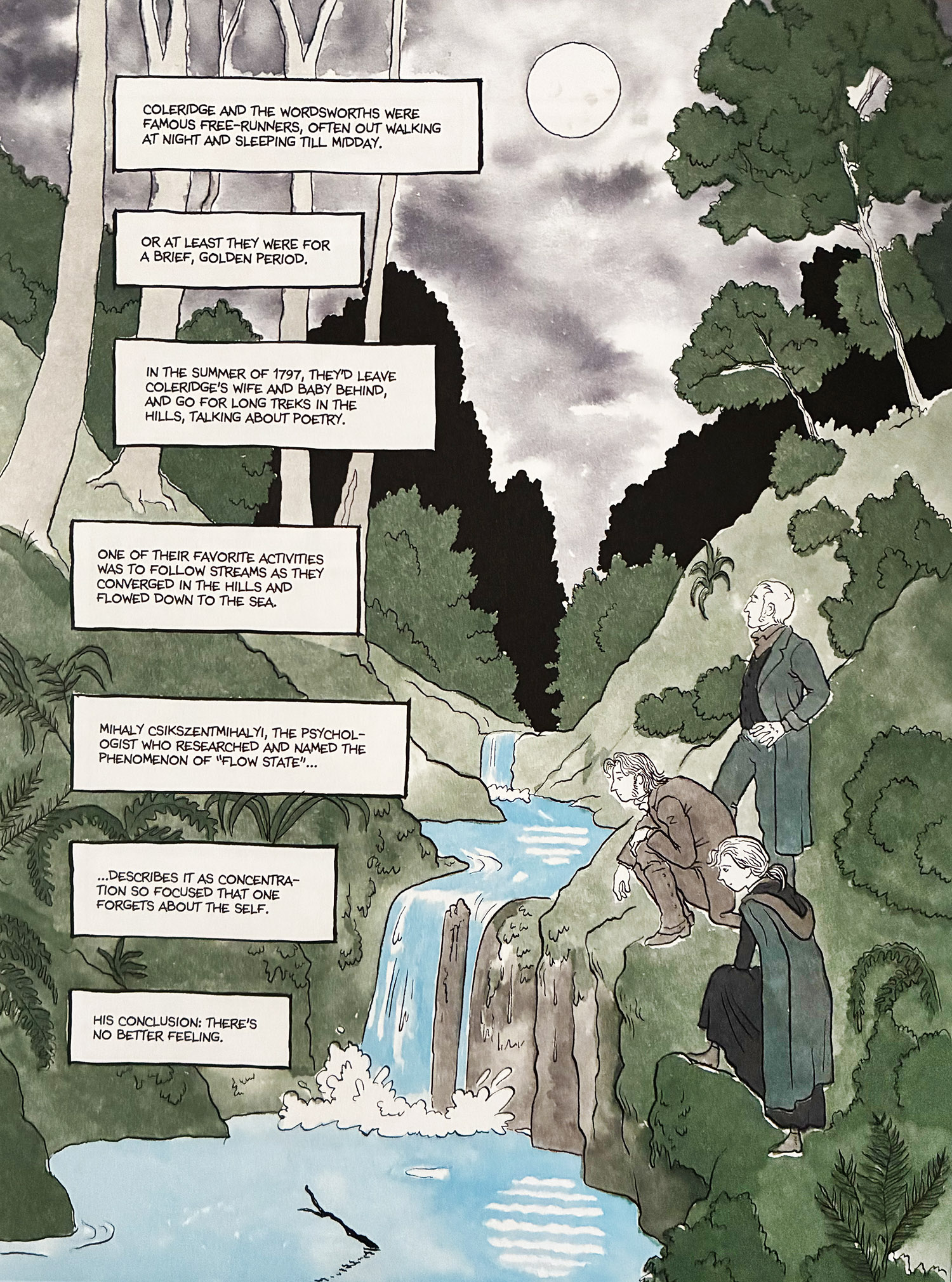

Both these books are printed in black and white. By contrast, The Secret to Superhuman Strength (2022) is in full colour, and correspondingly more cheerful. It introduces Bechdel’s partner, Holly Rae Taylor, and extends the choice of literary pre-texts: Wordsworth, Coleridge, Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Buckminster Fuller, Gary Snyder and Jack Kerouac all make an appearance, with vignettes of episodes in their lives shuffled into a decade-by-decade account of Bechdel’s quest for physical self-improvement.

Romantics on a quest, from The Secret to Superhuman Strength.

Bechdel draws attention to the persistence of Romantic ideals in the modern and postmodern world and emphasises especially the symbolic and actual challenge represented by mountains. The climax — reminiscent of the episode in The Prelude in which Wordsworth discovers he has crossed the alps without realising it — is Bechdel and Taylor’s failure to match Snyder’s (successful) and Kerouac’s (almost successful) ascent of the 12,000-foot Matterhorn Peak in Yosemite National Park, as told in The Dharma Bums. Once again, for the central character, failure is a via negativa, a form of progression, even when it doesn’t immediately seem to be so.

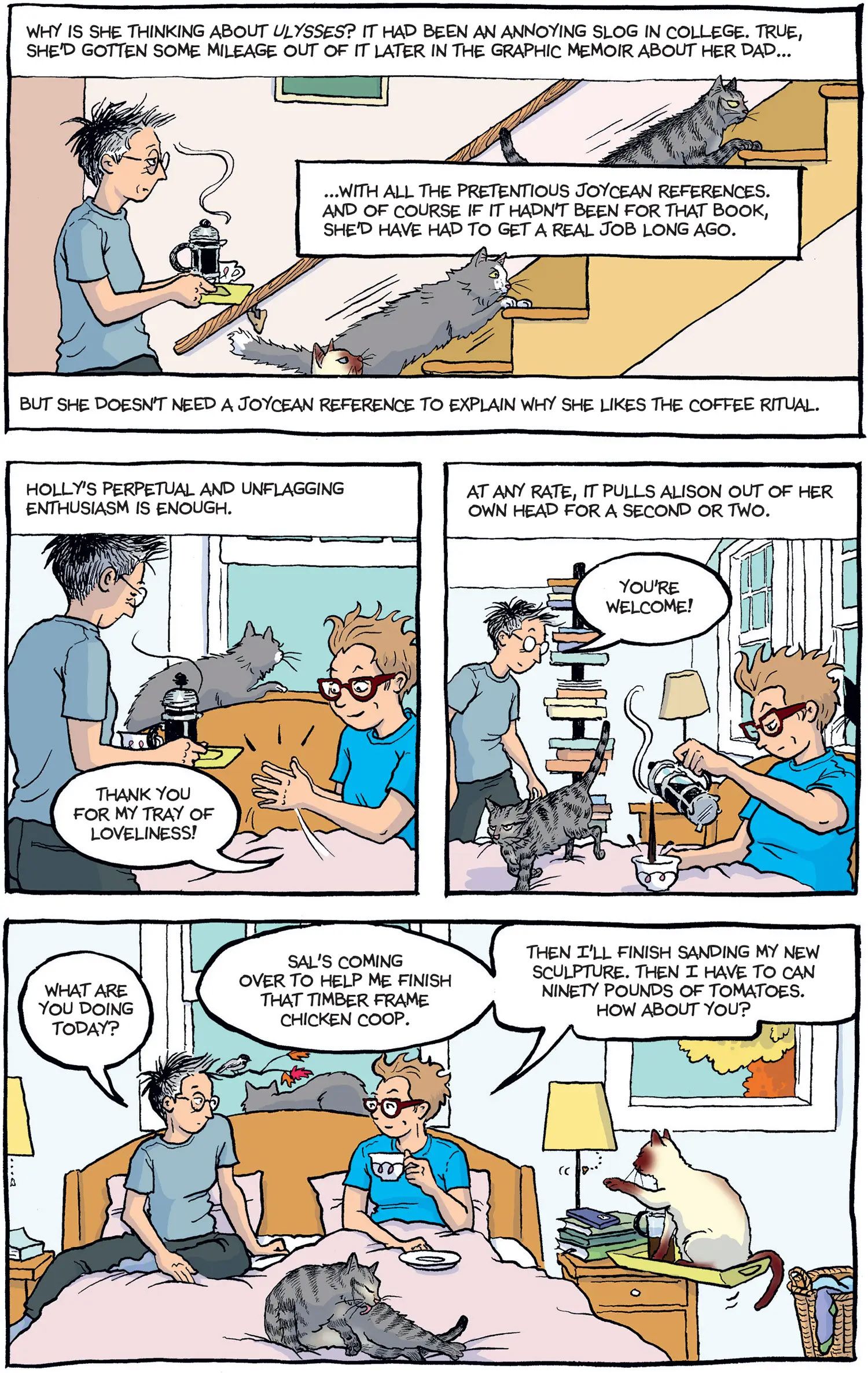

Spent, Bechdel’s latest work, is a very different book, more expansive, more enterprising, more forgiving about human quirks than its predecessors. It is a tightly woven semi-autobiographical comedy depicting small upsets and ructions in a rural bohemian idyll. The literary pre-text this time is Karl Marx’s Capital, and each of the twelve chapters is named with a quotation taken from it: “The Process of Production of Capital,” “The Expropriation of the Agricultural Population from the Land” and, the penultimate chapter, a fifty-word sentence, beginning “The circumstances which independently of the Proportional Division of Surplus Value…”

The adoption of Marx is both a jest at left-wing earnestness, and a frank admission that the consciousness of a class is shaped by the economic arrangements that underpin it (Marxism 101). Bechdel offers an acute diagnosis here of how her central characters’ worldview, their dominant attitudes, compromises and flashes of false consciousness, all depend on a dubious and predatory culture industry, a world of agents, show runners, big stars, TV studios, sitcoms, media behemoths, advances and, ultimately, royalties.

The main characters — who, for the moment, can be designated Alison and Holly — live in on a hobby farm near Lake Champlain, Vermont, surrounded by a community of like-minded friends. It is a semi-pastoral, tolerant, multi-cult world of gender fluidity, progressive politics and veganism (they boil their own tempeh). Social rituals include a community meeting opposing school book bans at which Alison, as the featured speaker, “drones on” while her friends in the audience check their phones or just nod off, and a farmer’s market that sells things like “non-binary menstrual products,” “AI Free” eggs (from “The Well-Laid Hen”) and “Vermonty Tchotchkes.” A more savage, less agreeable, America beyond is glimpsed when Alison makes a trip to LA via Chicago airport to pitch her TV show.

The book is far more complicated than this summary might suggest. For a start Bechdel replaces her old straightforward authorial personas with avatars of those real-life existences: the autobiographical characters in Spent are not Alison Bechdel and Holly Rae Taylor but versions of them whom we should style, adopting the genre’s hand-lettered caps, ALISON and HOLLY. ALISON and HOLLY are joined by a huge cast of characters. Some of these are fictionalised versions of real people, like BILL MCKIBBIN, BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH, AUBREY PLAZA and even SANDI TOKSVIG. Others, showing Bechdel’s inventiveness as the creator of typical or representative figures, are newly invented for Spent: the Gen Z Covid refugees from Brooklyn, SASHA and SHAKTI, and strikingly, SHEILA, ALISON’s straight, neo-con, Republican-voting sister, the bane of ALISON’s existence. SHEILA is the creator of prize-winning Seed Art (cute pictures made of millet seeds etc.), the author of a counter-narrative to Fun Home and Are You My Mother?, and, according to a momentarily non-PC ALISON, is “ON THE SPECTRUM.” (From here on such quotations will also be in small caps).

Alison and Holly’s rural idyll, from Spent.

A number of interesting and important intertextual characters is lifted directly (as one can discover from the very good compilation, The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For) from Dykes To Watch Out For. The main ones are LOIS, SAMIA, GINGER, and SPARROW. This ethnically varied quartet is part of a long-running longitudinal study of communal living conducted by the sociology department of the University of Vermont: “PEOPLE COULD MOVE IN, BUT THEY COULDN’T MOVE OUT.” LOIS, SAMIA, GINGER and SPARROW have thus been trapped in each other’s company for the best part of forty-two years. They are all lesbian, although SPARROW is bisexual, skewing hetero as time goes by, eventually forming a relationship with STUART, who becomes a late addition to the household (by the time of Spent a fixture for nearly thirty years).

STUART is a reluctantly tolerated, apologetically straight, tokenish male, although with firm opinions when it counts. The hooking-up of SPARROW and STUART occasioned dismay and scorn in the communal household. No one could see anything attractive about STUART, and he was, of course, straight, male, etc.: SPARROW could stare down a lot of this but even she was forced to admit (with Annie Leibowitz’s good fortune in mind) “HE’S NO SUSAN SONTAG.” Still, STUART wants to fit in: at one point he declares he is a Butch lesbian in a straight man’s body (GINGER: “SOFT BUTCH. MAY BE.”), he wears a skirt throughout Spent and eventually gets to act out his dream.

These people, back in the day, were cutting-edge youngsters; now, in the early-twenty-first century, they have settled into comfortable late middle-age — typical boomer oldies, in other words, with burdens and problems with which even the straightest boomer household could sympathise.

Their lives are brought together in an intricate satire of social manners and sexual mores in the progressive provinces. (The county of Vermont where they live voted more than 80 per cent for Kamala Harris.) They are likeable, decent, well-intentioned, principled adopters and upholders of all progressive causes, buffeted by veering headwinds, trying to make sense of a world that resists their best efforts to improve it — the archetypal crooked timber of humanity, earnest, humorous, quarrelsome, wryly self-aware, ruefully acquiescent, but wanting to perform the good, etc., etc., etc.

The burning personal question is no longer “what is my gender identity?” but “am I attracted by polyamory and the challenges it might present to my pretty standard commitment to monogamy and faithfulness?” The polyamory plot is edgy but within comic parameters, partly because the people involved, two lesbians and one rather dopey straight man, are all of a certain age, at a stage of life not typically associated with such adventurousness.

ALISON and HOLLY live off the royalties from a book and TV spin-off series called Death and Taxidermy, a work that closely resembles Fun Home: A Family Tragicomedy and its spin-off, the celebrated Broadway play of the same name. The TV series is about to end, and in one amusing drawing we see the book’s characters gather to watch a crazy penultimate episode with a humiliated ALISON squirming at the liberties taken with her story. When, in the not-too-distant future, the show ends, the money will dry up, and so ALISON, as bread winner, forces herself to devise, draw and pitch a new work, a progressive sitcom called $um, that will secure a future for her and HOLLY. As well bringing in the needful cash, $um will “HELP MY FRIENDS LIVE MORE ETHICALLY,” or so ALISON persuades herself.

These noble, if self-serving, intentions are frustrated by a system in which everything is contaminated by the online, post-industrial, digital, commodified age. When the sitcom pitch fails in chaotic scenes in treacherous LA, ALISON manages to clinch a last-minute book deal for the same idea with a Murdoch-like publishing giant named Megalapub. The self-reflective nature of all this is clear enough: $um is a parodic double of the Spent we are reading, and just as $um is to be published by the Murdoch-like Megalapub, so has Spent been published by imprints owned by an actual Murdoch publishing empire. One might even suspect it will end up as a TV series. Bechdel called Are You My Mother a “metabook” and Spent is a clever, more fully worked-out version of that genre.

The main business of Spent is the story of SPARROW and STUART. At the start they are a mildly discontented monogamous couple. The change agent is NAOMI, an interloper from the earlier world of Dykes (she appeared in the very first panel), casually encountered in the local store, to whom both STUART and SPARROW are feverishly attracted. It is hard to fathom NAOMI’s sexual irresistibility, but a throuple is formed, tame at first, soon full-on. The theme of people deciding their existing relationship is played out, along with a quest for pastures new, is echoed diminuendo in the lives of other characters: GINGER has pangs of jealous envy when SAMIA goes alone to Florida to escape the Vermont winter, and ALISON, suspecting HOLLY of betraying her with the local vet, finds herself musing on the likely pleasures of polyamory.

A crucial plot point is the appearance of STUART and SPARROW’s daughter, JAIO-RAIZEL, whose birth was movingly shown in Dykes back in 2003. Understandably, JAIO-RAIZEL, whose part-Chinese part-Jewish heritage is signalled in her unusual name, now styles herself (possibly “themself”) JR. She bears a passing resemblance to Greta Thunberg. Along with her friend BADGER, JR arrives home unexpectedly one midnight, just when STUART, SPARROW and NAOMI are heavily into their first night of sixty-something sexual experimentation and rapture — all this shown in scenes requiring Bechdel to draw pictures so forthright that they feel like an invasion of the privacy of the people involved (parental guidance recommended, i.e., completely unsuitable for parents).

JR and BADGER have dropped out of college and an asexual polycule, an arrangement that fell apart after two of its members, YAZU and LYRIC, realised they were not asexual after all, had sex and, and — so the implication is — were caught in the act by JR. SPARROW and STUART’s reaction to being similarly almost-discovered in flagrante delicto by their daughter is one of intense, thoroughly bourgeois, shame — their first thought is to order Naomi to hide under the bed (she is furious). From this point they do all they can to keep their sexual arrangements from JR and BADGER.

Monogamy vs. polyamory, sexual vs. asexual polyamory, are not the only sources of intergenerational friction. One of the most amusing strands in Spent is the readiness of JR and BADGER to administer correctives to a well-meaning but error-prone older generation. These come in the form of withering asides, such as when BADGER consoles a disappointed ALISON: “I’M SORRY YOU DIDN’T SELL YOUR SHOW. EVEN THOUGH THE PREMISE WAS UTTERLY SELF-CONTRADICTORY.” As the double-barrelled, high-calibre unacknowledged legislators of this world, JR and BADGER are a standing reproach to the complacency of the older folk with their finicky regard for convention and the law. When JR sets up a mail-order business in the family kitchen to supply abortion pills to “PREGNANT PEOPLE IN THE RED STATES” SPARROW objects on the grounds that the scheme is illegal. JR: “THIS IS SUCH WHITE SUPREMACIST SETTLER COLONIAL PATRIARCHAL NEOLIBERAL BULLSHIT!” (The unworldly STUART, it should be added, positive about anything countercultural, thinks it’s a great idea — or perhaps he just adores his daughter.) As a result, JR and BADGER move house once again and, in another midnight surprise arrival, seek refuge in ALISON and HOLLY’s yurt. (Young people. They don’t get that The University of Vermont Longitudinal Group House Study Project is like the Hotel California: you can check in but — so the idea is — you can never leave.)

After a vegan dinner prepared by JR and Badger in Spent, the group household discusses Badger’s anti-vax parents

JR and BADGER support Extinction Rebellion, and in a climactic scene, they break into a local natural history museum and video themselves throwing oil over a huge stuffed polar bear, an attack that links JR’s story to the ALISON Death and Taxidermy plot. Reluctantly sprung from a community correction order sentence, JR issues another fiat: “YEAH, COMMUNITY SERVICE IS CONSIDERED PUNISHMENT. JUST ONE MORE EXAMPLE OF HOW FUCKED THE WORLD IS.”

Eventually, at a wonderful-looking Lammas bonfire eve celebration, SPARROW and STUART confess what’s been going on. Far from being horrified, JR’s flying embrace is so powerful that it almost knocks her parents off their country haybale: “OMIGOD THAT IS SO BEAUTIFUL!” NAOMI is instantly accepted: “MAMA NAOMI! MY OTHER MOTHER!” Even the depressive BADGER concedes this is “PRETTY RAD,” adding rather sadly, “WHEN I LEFT FOR COLLEGE MY PARENTS JUST GOT A DOG” (they did, however, give her a BMW).

The book concludes with everyone watching the final bizarre episode of Death and Taxidermy, in which ALISON’s father is carried off by a dragon and dropped into a volcano. (Spoiler alert: just a dream.) JR: “IN-FUCKING-CREDIBLE.” They then emerge from the house into a beautiful evening, beautifully drawn and beautifully coloured (the book’s colour palette is ravishing). It’s JR’s suggestion that they should hang around for a bit just in case they get a chance to see the spring sky dance of the male woodcocks (or as she phrases it, “THE WOODCOCKS ASSIGNED MALE AT BIRTH”).

The woodcocks oblige — “THEY FLY UP REAL HIGH IN A SPIRAL AND THE WIND IN THEIR FEATHERS MAKES A TWITTERING SOUND” — making for a lovely double-page final spread. The framing moral of the story is given to STUART, big softy that he is, in words he has had freshly tattooed across his back: “PRACTICING MUTUAL AID IS THE SUREST MEANS FOR GIVING EACH OTHER AND TO ALL THE GREATEST SAFETY, THE BEST GUARANTEE OF EXISTENCE AND PROGRESS, BODILY, INTELLECTUAL AND MORAL.” (HOLLY: “WOW, THAT’S AWESOME STU! KROPOTKIN?” It is, from Mutual Aid.) SPARROW and STUART, judging from Fun House and Are You My Mother?, are the parents Alison Bechdel didn’t have.

In some ways Spent is reminiscent of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard. The world it sets before us is seductively idyllic, the characters who inhabit it are privileged and loveable, if at times a bit daft, and the humour is droll, benign, pleasingly salted here and there with a grain or two of malice. There is a sense of a world protected from harsher realities without, and who wants it to be in any different? Still, as in The Cherry Orchard, the outside world is there, and on the verge of cataclysmic change. One can sense it — too many strings are being snapped, and too many axes, freshly sharpened, are ready to be laid to the trunks of too many cherry trees. Spent begins in the autumn of 2022 and ends in the spring of 2024. The sky dance of the woodcocks takes place six months before the election of Donald Trump. •