Malcolm Turnbull and Coalition spin merchants in the media have told us that this was Labor’s second-worst vote since Moses was found floating on the stream. They’re right – but that’s only half the story.

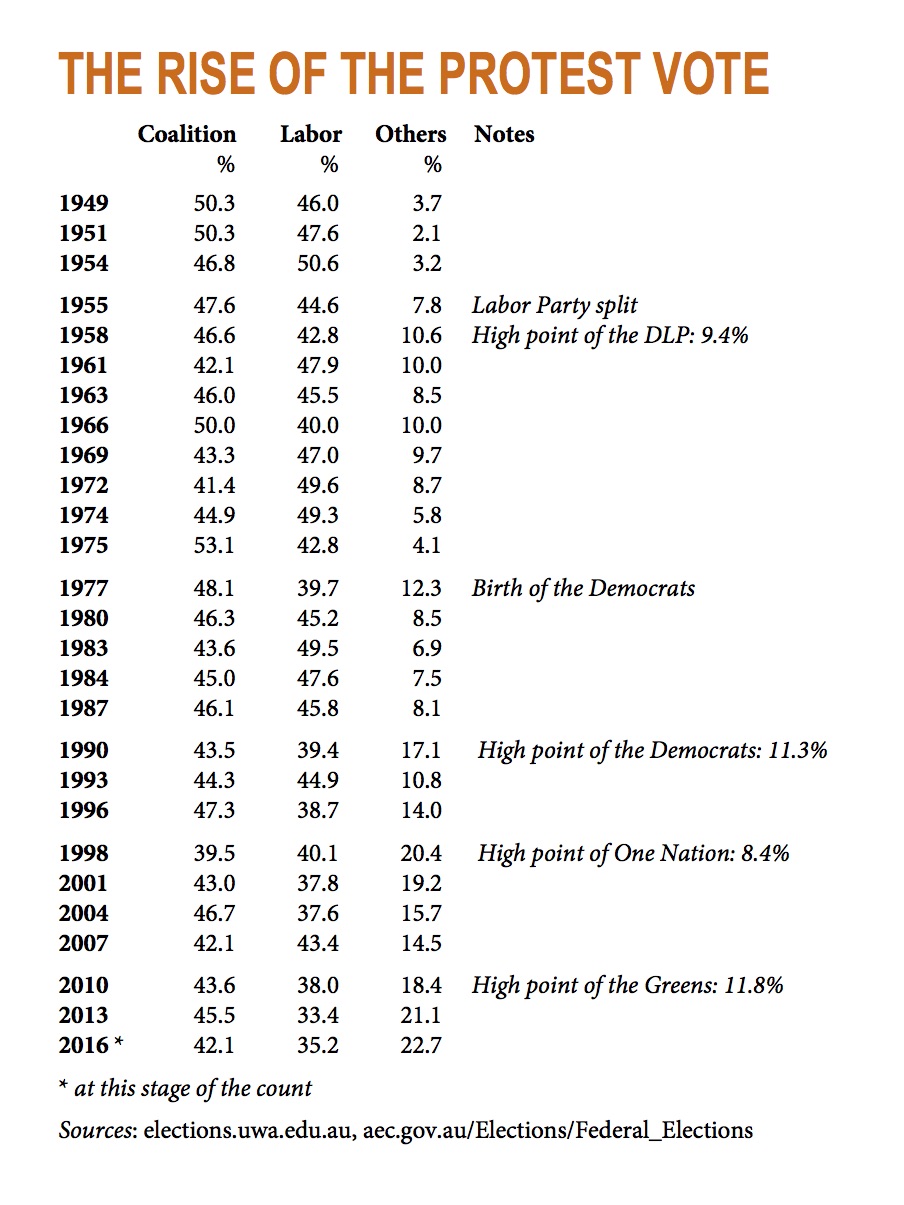

The half they’re not telling us is that the vote for the Coalition is also at historic lows. On current figures, it is 42.1 per cent – and that is the equal third-lowest vote the Coalition parties have recorded in the twenty-eight elections of the postwar era. It is not one side of politics that has lost support from voters – it is both.

Sixty-five years ago, in the double dissolution election of 1951, 97.9 per cent of Australians voted for the Coalition or Labor; this time, the figure was just 77.3 per cent. In 1951, only 2.1 per cent voted for someone other than a major party; this time, 22.7 per cent did.

Is that because our politicians are out of touch with the concerns of ordinary Australians? Plenty of people think so. When Coalition or Labor frontbenchers spoke to us in the campaign, most of what they said seemed targeted at impressing their rusted-on supporters, not the undecided voters you would expect them to be out to persuade.

If either side was in touch with voters’ concerns, the eight weeks of campaigning would have changed the way we think. But our voting intentions began in May at 50–50 and ended in July at 50–50. If one campaign changed any votes to its side, it was cancelled out by votes changing to the other. Neither side broke through.

True, the 24/7 news cycle has made the job of the major parties harder. The news media is now more partisan (the Murdoch press for most of the campaign was a PR arm of the Liberal Party, and Fairfax too often fills the same role for Labor), less interested in policy, and more demanding and less reasonable in giving the government or opposition time to work through issues in the best way. This erodes our confidence.

Yet I think there’s another side to it that we haven’t recognised. And it’s something not to bemoan but to celebrate.

What’s happened in our politics is the same phenomenon that has upended the status quo in the media, many areas of business, sport, the arts, everything. We now have more choice.

Thirty years ago, we had just five television channels. Now we have hundreds, and even they face competition from new online streaming services like Netflix. Owning a mainstream TV channel was once the path to riches. Now it’s more often the path to bankruptcy. But are we the poorer for our new galaxy of choices? Don’t be ridiculous.

Newspapers are finding life very hard. The information they once monopolised is now instantly available, at the click of a keyboard, in far more detail than a newspaper could ever provide. In industry after industry, fewer people are now in the mainstream, as we have headed off into hundreds and thousands of different streams of interest. We are losing once-beloved icons, but overall, we are much richer for the new access to information we have, and the new choices we have.

Even the sports we play have changed. Travelling down the Hume Highway recently, I pulled into Tarcutta to pay homage to the tennis courts where Tony Roche learnt his extraordinary skills – and found the place semi-derelict. Our suburbs now have empty tennis courts wherever you look. Tennis is as good a sport as ever, but once it was a central activity in a society that didn’t offer many choices for recreation, and now it competes with so many other options.

It’s the same in politics. Once, the Coalition and Labor had a duopoly at election time. Now, they compete with dozens of other parties – so naturally their support has eroded.

Go back to that election in 1951, fought out between two legends of Australian politics, Bob Menzies and Ben Chifley. There were 121 seats in the House yet just 285 candidates. Most electorates had only two candidates. Some had only one candidate, and were uncontested. The biggest contest had four. Most voters had only two choices.

In the Senate, there were sixty seats and just 112 candidates. There were only three groups – the Coalition, Labor and communists – and fifteen independents. The Coalition won the House sixty-nine to fifty-two, its majority inflated by the rural gerrymander, while the Senate divided thirty-all between the two sides. There were no crossbenchers in either chamber. The only candidates to come close to challenging the duopoly were former MPs who had lost preselection.

What a contrast to the 2016 election. This time, the 150 seats in the House had 994 candidates. The average seat had six or seven candidates. Some had up to thirteen. There were forty-nine political parties, plus independents.

In the Senate, we had 631 candidates for the seventy-six seats. New South Wales alone had 151 of them, or 12.6 candidates per seat. Victoria had 116, and Queensland 122. Each of those states had more candidates than the entire country had sixty-five years ago. No fewer than fifty-four parties or combinations of parties competed for our Senate votes.

Is that a good or a bad thing? Well, it gives us a lot more choice than we had in 1951. (Personally, I think we have too much choice, at least for the Senate: most of these parties have no chance of winning a seat, and past election data shows that the more parties we have, the higher the informal vote. Elections are very expensive, and it would be fair to double the deposit that candidates contribute to $2000 for House seats and $5000 for the Senate.)

But would we rather have fifty choices or three? The answer is pretty obvious. And it should be equally obvious that this is the main reason why fewer of us now vote for either of the major parties.

And why has Labor’s vote declined so much more than the Coalition’s? The key reason is that it now has a major challenger on its side of politics – the Greens – whereas on the right, all the competing forces remain minnows. Because there are so many of them, none can ever grow big enough to challenge the Coalition’s dominance of the right in the way that the Greens have eaten into Labor’s dominance of the left.

The battleground that matters for minor parties is the Senate; let’s look at their votes there. At last count, the Coalition had won 35.6 per cent of Senate votes, Labor 30.2 per cent, and all other parties 34.2 per cent.

• Of that, the Greens won 8.5 per cent, while some seventeen other left-of-centre parties (defined by mutual preferences swaps) won 5.2 per cent. The Greens will have about 9 per cent once absentee and pre-poll votes are counted, almost twice as many votes as the other seventeen parties combined.

• On the right, twelve small parties together shared 12.8 per cent. By far the largest was Pauline Hanson’s One Nation (4.3 per cent). Others included the Liberal Democrats (2.0), the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers (1.4), Family First (1.3), the Christian Democrats (1.2), the Democratic Labor Party (0.7) and Katter’s Australian Party (0.4).

All of these seven parties have (or will have) some parliamentary representation at federal or state level. But they have just sixteen seats between them in Australia’s fifteen parliamentary chambers, and the biggest of them – thanks to its close relationship with “preference whisperer” Glenn Druery – is the Shooters party, with six shooters in the upper houses of New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia. By contrast, the Greens have thirty-three.

It sums up the crippling lack of unity on the right that when some disgruntled conservatives wanted to oppose Muslim immigration, they ignored all these existing parties and set up yet another one: the Australian Liberty Alliance, which ran in every state but won just 0.7 per cent of our votes – and no seats.

If these parties seriously want to influence Australian politics, wouldn’t it be more sensible for them to merge into one conservative party, on the right of the Liberal Party? Yes, but the reality is that they operate as vehicles for someone’s dream to become a senator or MP. To unite behind one candidate would require the others to sacrifice their own dreams of becoming an MP. Human nature rules that out.

That would change only if their grassroots supporters abandoned the little parties to unite behind some charismatic leader who is already a public figure. That’s been the key factor in the success of every minor party (except perhaps one) that has ever become a significant force in Australian politics.

Don Chipp founded the Australian Democrats as a centre party when he broke from the Liberals. Pauline Hanson, charismatic to some because she was so unusual in Australian politics, made One Nation briefly a force in Queensland. Bob Katter and Clive Palmer did the same in more recent times.

Bob Brown, already a national figure after leading the successful campaign to save the Franklin River from dams, established the Greens as a political force. More recently, Nick Xenophon, having become well known in South Australia, has picked up the Democrats’ former support base there (itself inherited from the Liberal Movement, set up by former premier Steele Hall) and has taken it to a quite different level, attracting voters by offering plain speaking, a focus on their concerns, and clean politics.

The only significant party lacking a charismatic leader was the DLP. But it did have a charismatic leader behind the scenes: archbishop Daniel Mannix, its spiritual leader, who gave it the strong support of the Catholic church in Victoria, and influenced some churches in other states to do the same.

Is there a respected leader who could pull conservative supporters away from the Liberal Party and these little parties to form a conservative party with real weight? I doubt that it’s Cory Bernardi. I doubt that it’s Pauline Hanson. Indeed, having forecast three days after the 2013 election that the Palmer United Party senators would soon break from Clive Palmer’s control to make it Palmer Disunited, I will similarly forecast now that if One Nation does win three or four Senate seats, as it might, it too will become many nations before three years are out.

Realistically, the only figure who could lead a right-wing counterpart to the Greens is Tony Abbott. But he already leads a far more substantial conservative group within the Coalition, and you would assume he is staying in parliament because he aspires to return at least to the ministry, and preferably to the leadership of the Liberal Party.

So the little parties of the right will remain little parties. They officially directed preferences to each other at the Senate election. But as they didn’t have the resources to staff more than a fraction of the 7500 polling booths, or to advertise in the media, it will be surprising if their votes have much effect when preferences are counted.

In most states, the small right-wing parties scored between them far more than the quota needed to elect a senator. But with no strategy to make that happen, it is not clear that any outside the Hanson camp will actually be elected. One Nation could be the only party of the right on the new Senate crossbench. •