I lived in Melbourne for (slightly) more than half my life, from 1983 to 2014. And although I never really thought of myself as a Victorian, I was glad I lived there rather than the obvious alternative of Sydney, where my parents had lived until the day after they married.

But during those years I often thought that, notwithstanding Victoria’s image of itself as Australia’s most progressive state — which was in many respects true — there was nonetheless an authoritarian streak in its governments. And the most obvious illustration was their penchant, whatever their political complexion, for using the police as an adjunct to the State Revenue Office.

Anyone who has driven in New South Wales will know that signs tell you where the speed cameras are — so much so that if you do get caught by one, you really deserve to be booked for driving without due care and attention, too, because it’s that obvious. The police there also take double points off drivers who get booked on long weekends or public holidays. That’s because they actually want you to slow down… and if you don’t, they want you off the road.

Victoria, by contrast, has a lot more “road safety devices” (as they call them, with a nod to Orwell) — no fewer than seven on a short stretch of the Craigieburn bypass, for example — but they don’t tell you where they are, and they don’t take double points for offences on long weekends or public holidays. They also create lots more opportunities to catch you by having frequent speed limit changes over relatively short distances as you arrive in or leave country towns. And that’s because they don’t want you off the road as much as they want your money.

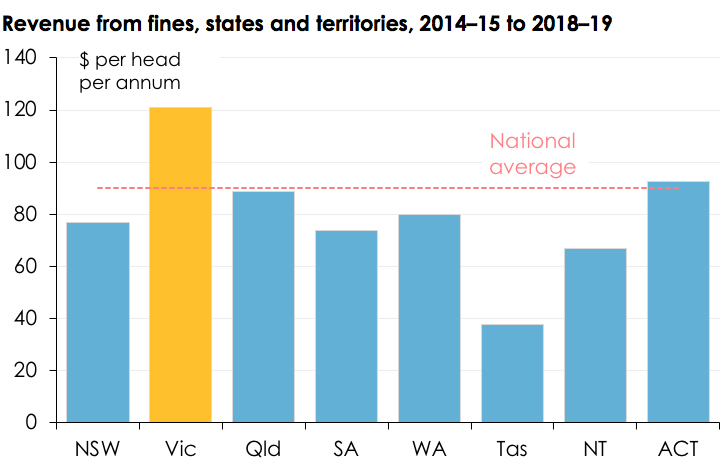

So it’s no surprise to discover that over the five years 2014–19 (the half decade before the pandemic) Victoria collected an annual average of $120.96 per head by way of fines. The all-states-and-territories average over this period was $89.95, and the only other jurisdiction that collected more than the average was the Australian Capital Territory, on $92.51.

Put differently, the average for all states and territories other than Victoria was $79.30, which is $41.66, or 34 per cent, less than Victoria. The NSW figure was $76.96, and in Tasmania, where I live, the police actually give you a warning for a first offence rather than take money off you — which helps explain the state’s figure of only $37.57. And remember, fines are intrinsically regressive — they hit poor people harder than rich people by taking a bigger share of their income.

Source: State and territory budget papers; ABS population data; author’s calculations.

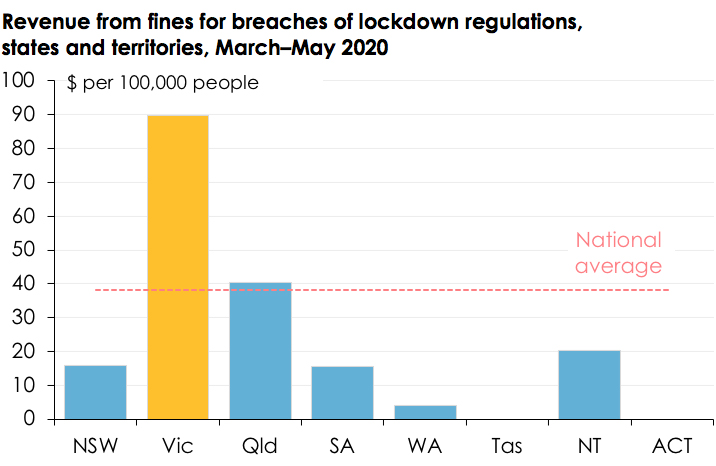

Victoria’s approach carried over into the pandemic. During the first lockdown, when all states and territories were imposing broadly similar restrictions, Victoria collected almost $6 million in fines for breaches of lockdown restrictions, $2.2 million more than every other state and territory put together. Per 100,000 people, Victoria collected $89.90. The average for all other states and territories was $20.10 per 100,000 people. New South Wales, which had the same risk profile as Victoria — with Sydney and Melbourne being the principal points of entry into Australia for foreign visitors and returning Australians — only collected $15.90 per 100,000 people.

Source: Tammy Mills, “Ahead on Penalties: Victoria Leads Nation on COVID-19 Lockdown Fines,” Age, 28 May 2020; ABS population data; author’s calculations.

Were Victorians really four and a half times more likely than other Australians to breach lockdown regulations? Did Victoria really have four and a half as many people, relative to its population, who saw themselves as sovereign citizens exercising their constitutional (or God-given) right to gather in large numbers in defiance of health advice? Or did Victoria impose bigger fines than any other state or territory, deploy more police in order to detect the necessary breaches, and “fine first and ask questions afterwards” to a much greater extent than any other state?

While it seems unarguable that the main reason for Victoria’s second wave was egregious failures in the management of hotel quarantine, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if the complacency that Dan Andrews detected among his fellow Victorians when the first lockdown regulations were eased wasn’t in some way a reflection of a sense of relief at getting out from under the most oppressive policing regime in the country.

And do you recall the Victorian government’s first action once it decided to lock down the twenty-eight public housing towers at the start of Victoria’s “second wave”? It was to send squads of police to surround the towers and fine anyone who might have been tempted to sneak in or out. It was left to volunteers to provide food and other essentials to the residents detained in those towers.

And when announcing the details of the renewed lockdown in early August, Dan Andrews openly bragged about the “opportunities” to impose “even bigger fines” on people who breached the new regulations. And of course this continued last week, when he proudly unveiled fines of $4957 (where do they come up with these numbers?) on people who attempt to breach the “ring of steel” between Melbourne and regional Victoria.

I’m not suggesting that laws or regulations imposed in the interests of people’s health shouldn’t be enforced, or that wilful or persistent breaches shouldn’t be penalised. But maybe, just maybe, there might be more effective methods than maximising the revenue gain to the state government.

The point is that Victoria’s heavy-handed, revenue-driven approach to enforcing lockdown regulations failed. It didn’t keep Victorians safe. The state government could have made different choices — not just about how it ran hotel quarantine, but also about how vigorously it policed lockdown restrictions, whether it instructed police to issue warnings for inadvertent or first-time breaches of lockdown regulations, the dollar amount of the fines it imposed, and so on. Other states, in particular New South Wales, made different choices — and also achieved much better outcomes. •