The Gillard Project: My Thousand Days of Despair and Hope

By Michael Cooney | Viking | $32.99

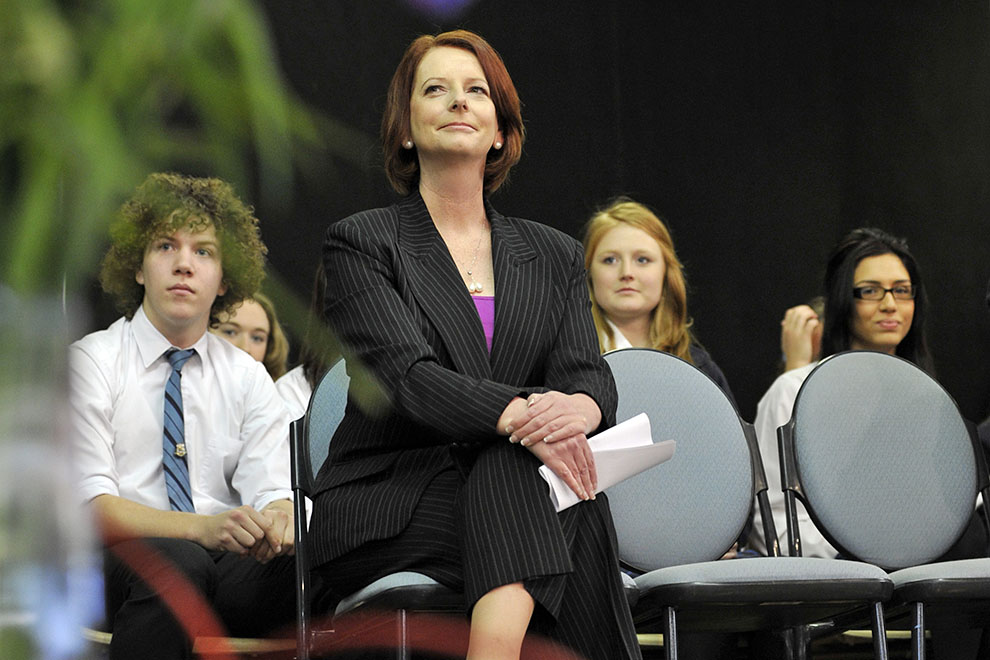

In this account of “the Gillard project,” Michael Cooney offers a solution to perhaps the deepest puzzle about our first female prime minister. How was it that Julia Gillard – with her parliamentary dominance, her policy smarts, her manifest skills in one-on-one negotiation and her sheer resilience – couldn’t translate all the markers of Canberra success into positive poll numbers and lasting public affection?

Cooney, who served as Gillard’s speechwriter for a “thousand days of despair and hope,” offers a new explanation. In her speech to the National Press Club in July 2011, Gillard volunteered a self-description of “the shy girl” from Unley High who brought “a sense of personal reserve” to the public profession of politics:

The rigours of politics have reinforced my innate style of holding a fair bit back in order to hang pretty tough. If that means people’s image of me is one of steely determination, I understand why.

“Personal reserve” is a useful protective screen for any politician. According to Cooney, though, it was much more than this, and not all of it good for the prime minister’s political efficacy. He suggests her reserve served as “a kind of bridge” between Gillard’s background and her political purpose as prime minister, giving her the sense she had more in common with “the kids in the back row” of the Unley classroom than with the “established and complacent faces” in the National Press Club audience.

In Cooney’s argument, this provided a constant reminder to Gillard of what she felt to be her unique political responsibility for the former, but also exaggerated her sense of isolation from the latter. Moreover, it became a heavy barrier to Gillard’s wider task of communicating with Australians who could never know her private self – as Cooney, from his vantage point within the prime ministerial circle, felt he could. Voters who only saw her media performances found her dour, wooden or mechanical. For a prime minister who is inextricably tied up in the business of connection, explanation and persuasion, this was a crippling disability. As Cooney notes with regret:

If you keep telling people popularity doesn’t matter to you, they can be inclined to reward you by agreeing… Sometimes you just have to make them smile; to say something they like hearing… Most of the days she was in office, giving the people everything of her life and services, Julia Gillard just couldn’t give them that.

Prime ministerial speechwriters occupy a very privileged position in contemporary democratic politics: close to the action and close to the leader, but protected from most of the political gunfire. Proximity provides insight into the exercise of great national power, as well as the responsibility of explaining, to the people in whose name it is exercised, the calculations and aspirations that inform it. Quite lacking in executive authority, the speechwriter and other advisers have the capacity through advice and influence to shape political outcomes: they are not principals but “policy midwives and policy grave diggers,” as I described them in my own account of life on the inside as Bob Hawke’s speechwriter between 1987 and 1991.

This privileged perspective no doubt explains the emergence of an odd little sub-genre in the rapidly expanding universe of Australian political literature. Alongside the autobiographies, policy tracts, insider narratives by journalists, and scholarly studies of political leadership, there is now a small series of books about former Labor prime ministers written by their speechwriters.

Cooney’s memoir – affectionate, partisan, thoughtfully articulate and with a nice touch of gallows humour – is the latest entry. His account is not as morbidly hilarious as James Button’s speechless experience with Kevin Rudd. He is more discreet than Don Watson’s recollections of a bleeding heart in Paul Keating’s office. He lacks the sheer whimsy of John Edwards (okay, an economic adviser not a speechwriter), who revealed Keating’s belief in the beneficial health effects of zenithal weightlessness experienced while bouncing on a trampoline.

Cooney’s memoir makes no scholarly contribution to the study of oratory, as does former Beazley speechwriter Dennis Glover; nor is it an anthology of our greatest modern speeches like the one edited by Keating speechwriter Michael Fullilove (which includes no fewer than eight Keating speeches). And, like all of us, Cooney falls short of the certain grandeur of Graham Freudenberg, whose grand narrative of the rise and fall of Gough Whitlam is a true work of history that continues to resonate after the death of its subject.

Yet The Gillard Project is a substantial contribution, exemplifying the principal claims to authority of this genre while also – I observe as a reviewer, but also as a contributor to the genre – displaying its characteristic weakness.

First, as Cooney’s acute analysis of Gillard’s “personal reserve” suggests, speechwriters are well placed to provide insight into the character of the leader and the course of events in their office and their government. Their accounts provide tiny capsules of contemporary political practice – artefacts of a way of political life, like oyster shells on a midden.

Their narrative authority derives from personal experience of “what really happened” – partial and subjective, of course, but sympathetic and informed. Working with the political leader over extended periods, striving to capture the very words and phrases that will best express their policies and win their arguments, speechwriters contribute to, but also see through, the wax and polish of the public persona to glimpse something of the personality beneath. Not their deepest soul, perhaps, but certainly their political character – whether or not they are figures of integrity, of energy and purpose, of intelligence and consistency; whether their “project” is fair dinkum or a sham.

A particular joy of the speechwriting gig is its almost infinite scope. Speeches traverse the whole landscape of government, travelling wherever the prime ministerial interest extends – which it does, into every important policy debate, every key economic issue, every defining social issue. Prime ministers speak to interest groups and community groups in every part of the country, they lead the campaign in every election, they speak on behalf of the nation in mourning and celebration, and they promote Australia’s interests and convey Australia’s identity in foreign capitals and international forums.

Details have changed over the decades – the issues, the technology, the media – but the job is essentially the same, and so the genre, from Freudenberg to Cooney, has become somewhat repetitive. Like a Scandinavian police procedural, there are only a certain number of locations and scenes in which the action can take place. Cooney’s book has got most of them: the Prime Minister’s Office, the Lodge, Kirribilli, the VIP jet, the hotel rooms at midnight in foreign capitals; a relentlessly rolling schedule of keynotes, launches, statements, set pieces, addresses and commemorations, with countless drafting sessions, staff meetings, staff drinks, gaffes and tiffs and what-ifs – and hours upon solitary hours in a “windowless” office in Parliament House.

When Cooney beats himself up for a full chapter about his “we are us” debacle (Gillard’s speech to the Labor national conference), I recall our own disastrous “child poverty” error at the 1987 election campaign launch. When Cooney travels with Gillard to Washington, where she addresses Congress for the sixtieth anniversary of the ANZUS treaty, or to Beijing to announce a strategic partnership, I recall Watson’s account of Keating’s nostalgic trip to Ireland to address the Dáil, or Hawke’s address in the Kremlin during the Gorbachev years, or our all-night drafting session in a Seoul hotel before he launched the APEC initiative. And these accounts in turn descend from the ur-narrative, Freudenberg’s account of Whitlam’s momentous visit to China as opposition leader in 1971.

All Cooney’s book lacks is a couple of election campaign stops – he was appointed after 2010 and the whole show was cancelled before 2013 – but he does have a charming and reassuring new location, the ocean off Bondi on a fine summer afternoon as the end drew near, where Gillard staff and Rudd staff could be found “bobbing up and down in the water drinking beer” – a model of unity which, he points out, caucus should have emulated.

Against these authoritative strengths, however, there is the generic weakness of all books by speechwriters. We are too in love with words, including our own words; we invest them with a power beyond all reason.

What is a speech? An arcane format that scarcely survives elsewhere in government, business or society. There was a good reason the press office was never too fussed about the speeches in Hawke’s day: they knew that what counted was not the forty-minute speech but the quick doorstop afterwards – the grab, not the exegesis. But speechwriters live and work in a tradition of political rhetoric; it’s a romantic world in which political causes are advanced through argument and persuasion, thesis and antithesis, framing and positioning, conducted by a prime minister who is passionate and articulate and who cares.

That world is, of course, not the real world, where politics operates as usual through numbers, factions and deals and where the best arguments can lose out to the basest slogans. So accounts by speechwriters are necessarily misleading.

And of course this romantic pathology seems to be peculiarly virulent on the Labor side of politics. That, after all, is the most obvious characteristic of this speechwriters’ genre: we are us, as Cooney might say, we male Labor speechwriters. Where are the accounts by Fraser’s people, or Howard’s? Can we expect anything from Abbott’s people at some time? It might be shame or it might be forgetfulness, but with the exception of David Barnett and Pru Goward’s admiring biography of Howard, no Liberal staffer has broken into print with their recollections, their insights, their advice.

But perhaps they don’t inhabit that romantic world. Cooney’s book provides the public with a valuable insight into the workings of a Labor prime minister’s office. The Liberals, by contrast, may be adhering to the old unwritten rule about what stays on tour when you go on tour. •