In a London hotel, two prime ministers sit down to breakfast. One is tall, lean, white-haired and speaks in a raspy, unmistakably working-class Australian accent. In public and private he smokes a pipe near constantly. The other is a protégé of Mahatma Gandhi who has spent over ten years detained in British colonial prisons in India, whose charisma and erudition have made him world famous; his preferred dress is an achkan, a knee-length coat. On this morning in April 1949, it’s fair to say, they appear to passers-by quite the odd couple.

The two men discuss a dispute that has brought newly independent India to the verge of leaving the Commonwealth. India seeks assurances that the postwar Commonwealth is a genuine association of free and equal members, not “led” by a still-imperial Britain. In the words of the Indian leader who sits here at breakfast, India needs to know that the Commonwealth cannot “bind [India]… in any way”; that there will be no inference of subordination to Britain; that India “has nothing to do with England constitutionally or legally.” India will not continue to place itself under the British Crown, given Britain colonised India in that Crown’s name. In sum, India is trying to ascertain whether remnants of the Empire shadow the postwar Commonwealth. Australia’s government has been an obstacle to these Indian aspirations.

But the Australian prime minister sitting opposite here at breakfast has just overruled his foreign minister and quietly conceded to India’s ambition to remain a Commonwealth member while becoming a republic.

Australia’s leader will subsequently call his Indian counterpart one of the great men of the world, while India’s leader will later say the Australian is an “outstanding personality” who was “very helpful” in London — indeed, he will soon ask the Australian leader to mediate in the dispute between India and Pakistan over Kashmir.

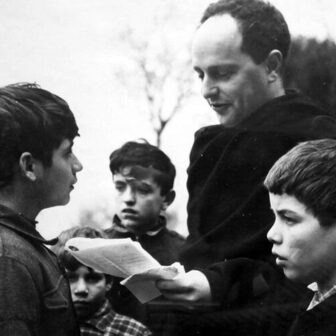

Such a meeting not only bodes well for the effort to preserve and reform the Commonwealth, which demands adroit, measured diplomacy. It suggests, despite much evidence to the contrary in these early cold war years, that means exist to prevent a global slide into acrimonious nationalisms and heightened global tension. It’s the first time they’ve met, but for both J.B. “Ben” Chifley and Jawaharlal Nehru it’s a productive morning.

Later, at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference they are in London to attend, Chifley and Nehru agree on other issues. Asia is currently in turmoil, with various wars and insurgencies ongoing in Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaya, Burma, China and India itself. When the conference discusses this situation, Chifley says he is “at one” with Nehru that “social conditions and living standards” in the developing world should be “the primary object” of Commonwealth policy. Such an approach, Chifley and Nehru agree, is also the most effective method of reducing communism’s growing appeal in Asia. Chifley, again echoing Nehru, adds that he thinks military solutions against communism are counterproductive. This view will be unwelcome to his British hosts, currently at war with a communist insurrection in Malaya.

It’s not all agreement. At another point in the conference, Chifley says, “We stand with Britain, right or wrong.” Nehru leans forward to reply, “Right or wrong, Mr Chifley?”

Chifley’s comment is surprising, because he has differentiated Australian policy from Britain’s on several issues, notably the Indonesian crisis in which, against Whitehall’s advice, he supports the Indonesian nationalist uprising against Dutch colonial rule. Is this platitude a reflex action — a sentiment Australian prime ministers typically express at these forums?

Nehru’s response is revelatory, showing what a different meeting of the Commonwealth this has already become, and to what Chifley, in accommodating India, is agreeing. Previously, the Commonwealth organisation was a forum for white men from British settler societies to coordinate the British Empire. It is now evolving into something fundamentally different: an organisation divorced from that empire, where the Asian nations that have become independent of British colonialism have membership and equal status, and voice their own attitudes and aspirations.

In the years that followed the second world war, global politics were remade. Across the globe, from world leaders to ordinary citizens, a conviction took hold that after thirty years of horrors — a world war, a Great Depression, another world war — profound changes were needed, that the times required boldness, creativity, new directions and far-reaching reforms. Similar opinions are beginning to be heard today, and a remade Commonwealth, with deepened engagement between African, Asian and Western members, could effect positive change. Chifley and Nehru’s responses to the Commonwealth seventy years ago offer lessons for our own time.

European colonialism began to unravel in the 1940s. It happened first in Asia: in 1945 there were revolutions in Indonesia against the Netherlands and in Vietnam against France. India, the site of Gandhi’s long, nonviolent resistance campaign, became an independent nation in 1947 when Britain, bankrupted and exhausted from the war, agreed to dissolve its Raj, the British Empire’s “jewel in the crown.” On becoming prime minister, Nehru gave voice to a prevailing sense of ambition when he declared, “A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

Europeans, used to running Asia for their own interests, had to adjust to this new reality. One organisation that plainly needed comprehensive reform was the Commonwealth.

In the late nineteenth century, “Commonwealth” began to be used to describe the relationship between Britain and those colonies — Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand — that had been granted self-government within the British Empire while continuing to share with it defence, foreign and international economic policies. In the early twentieth century, the Commonwealth found institutional form when Britain and those states — called “dominions” — met at imperial conferences to coordinate their actions. That all the colonies granted self-government and Commonwealth membership were white, and that India was not granted such status, did not escape notice; the prewar Commonwealth reflected the racial hierarchies at the core of European imperialism.

After the second world war, Britain invited the new nations of South Asia — India, Pakistan and Ceylon — to join the Commonwealth. It also linked membership to economic aid and investment, trading privileges and military assistance. Because these were fully independent countries, not dominions, it appeared that a postwar Commonwealth’s decision-making would be less prescriptive than prewar — but, on this issue and others, the British were deliberately vague. Use of paternalistic language to describe Asian nations’ entry into the Commonwealth clouded matters further. Denialism was rife; Britain and the dominions retained much of imperialism’s cultural baggage. According to Nicholas Mansergh, historian of the Commonwealth, “ideas did not keep pace with actualities; the imperial past bore in oppressively upon the Commonwealth present; attitudes appropriate to Empire were carried over into Commonwealth.”

Many in Britain and the dominions held onto a vision of the subcontinent that was not much different from the India of Empire — an idea, conscious or subconscious, that Indian independence had been a relatively superficial change. Sometimes, British and dominion governments pointed to their mutual interests with India in stabilising Asia; sometimes they continued to think of India — as during the Raj — as simply a provider of an “army for hire,” to be recruited as desired.

That Nehru had ruled out India’s joining any formal Western defence alliance and was pursuing close ties with other decolonising Asian nations — a strategy soon to be known as non-alignment — was something Britain and the dominions often downplayed or ignored. While some officials talked about trade opportunities provided by Indian economic development, when others spoke of Indian trade, they mostly invoked the need to maintain preferential access deals developed under the Raj. At a time when Nehru was crafting expansive industrial development plans — his inspections of hydroelectric dams became staple news footage — it was a startlingly narrow idea of the new Asia’s economic potential. It was common to pledge support for Asian decolonisation, but less common to look hard at exactly what the new Asia was, and what it sought.

In Asia, Commonwealth membership raised suspicions. Was the organisation a bid to retain Britain’s global “spheres of influence,” despite Britain’s decline? Or was it more of an international vanity project, a means to safeguard British pride by prolonging an illusion of British centrality at the expense of nationalist pride in the new Asian nations?

Nehru approached the Commonwealth with a blend of nationalist and internationalist inclinations characteristic of both him and the postwar age. He had been imprisoned by the British, but he was also educated at Cambridge. In prison he had written histories of India that portrayed the country as open to the world and to diverse cultural influences: he admired the ethnic and religious tolerance of former Indian emperors and emphasised India’s historic trade and scientific links with China, Persia and Arabia. He described, without self-consciousness, his emerging foreign policy as the pursuit of peace. His appeal crossed continents; he was beloved by Western left-liberals, and drew crowds in other Asian capitals. He embodied the dream of a “new” Asia, and the dream of a new, equitable relationship between Asia and the West.

Initially, Nehru had assumed India would leave the Commonwealth: his own party and Indian public opinion were in favour. But he had begun to rethink. If pragmatism — the material benefits of membership which Britain had promised — was driving him, so was a deeper idea of international cooperation. A nation, he told Indians in 1949, “cannot live in isolation.” His decision that India would join the Commonwealth as a republic with no link to the British Crown flummoxed many in Britain and the dominions, including H.V. “Doc” Evatt, Australia’s external affairs minister, who began to actively oppose the idea.

In Evatt’s mind, the issue of “the Crown,” and whether all Commonwealth members recognised it was far from a trivial matter. Evatt had been the first Australian foreign minister to forge an Australian foreign policy truly independent of London. At the same time he had, like most Australians in the late 1940s, a strong British identity: he was a patriot of what was still referred to as the “British race.” Evatt had grown up with “the Empire.” He had spent years in global diplomacy, meeting and working with the officials of that Empire. It was the world he knew — imagining a different one did not come easily. Evatt’s policy independence from Britain was unquestionably bold. But it also made him fall back on symbolic, sentimental cultural tropes as common denominators binding together that “British world” to which he still felt connected and which he badly wanted to view, against growing evidence, as a constant in an otherwise shifting geopolitical landscape. In the months before the London conference, Evatt’s attitude loomed as a significant impediment to the project of reforming the Commonwealth to allow India to stay.

Then Ben Chifley decided he, not Evatt, would attend the London conference at which India’s Commonwealth membership would be decided.

Chifley was keenly interested in Asia. He had been closely following events in India — so much so that when Australia’s high commissioner in Delhi briefed him, the commissioner was startled when “for two hours he told me” about events there. Now in London in 1949, sitting in the chair Evatt would otherwise have occupied, Australia’s prime minister acceded to India’s staying in the Commonwealth as a republic.

Chifley had often spoken about the extent of human suffering in Asia. He told parliament that, in Asia, too many “have not enough to eat… cannot look to the future for improved conditions.” He told his officials about the terrible poverty he had seen when travelling in Asia in 1933, and also said he considered European rule responsible. Chifley’s adviser H.C. Coombs remembered his boss saying, “When I think of the wealth [that has] flowed out of [India] to Europe it makes my blood boil.”

Chifley’s focus on unsatisfactory living conditions in Asia and his conviction that such conditions were intolerable were based on hard analysis of what had gone wrong in the world during his lifetime, and what now, in the late 1940s, he thought needed to be corrected. For Chifley, the paramount political lesson of the years since 1914 was that underlying conditions in societies — widespread misery, unmet aspirations, unsatisfied grievances — risked profound destabilisation within countries and in the international system. Chifley had seen mass unemployment and inflation in Europe steadily increase the appeal of fascism and other radical ideologies. He had watched Japan, cut off from food supplies and markets, turn to militarism. A better world, more accommodating of human needs, was not merely desirable, but acutely necessary to help stabilise the international order.

Such thinking was widely held in these years, especially on the political left, and led to far-sighted policies of reconstruction in Europe and Japan. Chifley, inclined to think first of Australia’s own region, was unusual in his systematic attention to decolonising Asia. The region was in chaos, experiencing war and unrest, because people were desperate for change. Chifley viewed Asia the way he saw politics generally: what was needed was broad-based opportunity, inclusion and justice. This meant supporting Asian movements that were pressing for and embodying positive change.

Chifley also envisaged wide economic benefits from a future Asia. But the benefits he saw were not limited to individual export markets and preservation of imperial access. During the Great Depression, Chifley had seen how poverty and weak economic demand created a vicious circle: because people in poverty could not spend, businesses had little demand for their products, so economies were perpetually stalled. Along with Coombs, Chifley thought Indian and other Asian economic development, industrialisation and rising living standards would help stabilise and boost the economy in Australia and the world more generally, because hundreds of millions of Asian consumers would power economic demand. Such stimulus would help prevent both another depression and forms of extreme politics feeding on poverty and distress.

But the star of the London conference was Nehru. When South Africa’s prime minister, Daniel Malan, said, “The Crown was indivisible… the King could not be king of this, head of that, perhaps emperor of something else,” Nehru replied, “Have you perhaps heard of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost?” When New Zealand’s prime minister Peter Fraser asked if India was committed to mutual defence, as the prewar Commonwealth had been, Nehru said he disagreed with Britain on many policies and would accept no such obligation. His statement — and other members’ grudging tolerance of it — conveyed beyond doubt that the prewar Commonwealth was dead and this new Commonwealth meant non-binding consultation among independent states. But Nehru, too, compromised; while the King would not be India’s head of state, he would remain head of the Commonwealth.

In the relatively unassuming position Chifley adopted lies the significance of his contribution. His own preference was, like Evatt, for India to recognise the Crown. But Chifley thought Nehru’s India to be an important country; he wanted it in the Commonwealth. Its position had to be respected — and so, he accommodated. According to John Burton, then head of Australia’s Department of External Affairs, Chifley was “obviously upset” after Nehru’s “right or wrong” challenge, pondering the exchange and what it meant. Such reflectiveness is a valuable trait in international diplomacy.

Chifley’s primary motivation was not to advance the economic and other interests of the “British family”; he was never nostalgic for the glories of the Empire; he didn’t see Asian engagement as simply a means to secure a future for the Commonwealth. Rather, Chifley saw a new Commonwealth as a means to enhance East–West cooperation. That hope was bolstered by his encounter with Nehru.

There is talk nowadays of Commonwealth “values,” much of it vague. Chifley and Nehru, though very different men, shared real values. Both were social democrats determined to use state power to reduce economic inequities and human suffering. Both were influenced by Fabian socialist ideas that had originated in Britain — a reminder that progressive as well as reactionary ideas can travel along imperial networks. They also shared a fear of war. Chifley told his parliament that “every public man has a duty” to do everything possible to avoid another world war. Nehru, according to biographer Judith Brown, was similarly “haunted” that another war would “wip[e] out any semblance of civilisation.” Sobered by their experience of the world’s thirty-year crisis, Nehru and Chifley shared a seriousness of purpose; both sought solutions to intractable problems and durable bases for interstate cooperation.

Today, the relative rise of the East and decline of the West is accelerating. India and other Asian and African nations have fast-growing economies. Nationalist sentiment, and a renewed focus on the colonial past, are also growing.

In this context, British prime minister Theresa May’s 2016 trip to India was remarkable. May, like in-denial British and dominion officials in the late 1940s, acted as if modern India is not much changed from the Raj. Despite Indian demands for a reckoning with British imperial atrocities, no apology or even sober reflection was offered. May spoke narrowly of bilateral trade prospects, with her vision of this decidedly one-way: she only briefly mentioned Indian companies and investment into Britain, and dwelled mostly on British companies entering India. Most obviously, May failed to heed the aspirations of those with whom she wished to partner. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi was clear about what India sought in any future relationship: “greater mobility… of [Indian] young people,” he said, will “define our engagement.” Committed to cutting British migration, May offered nothing on that issue. She left India with little of substance.

If the Commonwealth were now to be reformed again, this time to address the changing conditions of the twenty-first century, it could be an invaluable organisation. The Commonwealth’s imperial beginnings — providing it with a membership of both formerly colonised and coloniser nations — give it particular promise as a forum to discuss and resolve contemporary East–West tensions. European imperialism’s legacies still shape the world. There are Western biases in international bodies; double standards in trade, migration and environmental accords; exploitative actions by Western multinational corporations.

Given growth rates in non-Western nations and the political power shifts set to follow, the twenty-first century’s political foundations will be unstable without a new set of East–West compacts, more favourable to the East — compacts making international power relations more equal, genuinely mutually beneficial. The Commonwealth could lead the way on such a process of reform, becoming a laboratory for new arrangements to tackle outstanding East–West issues: climate change, large-scale migration, access to education and employment, regulation of transnational capitalism, reform of international institutions, elimination of barriers to agricultural and other developing-world exports.

In developing such a reinvigorated Commonwealth, Chifley and Nehru are useful sources of inspiration. Today’s world is beginning to resemble those years of crisis — economic misery, political extremism, antagonism risking war — that Chifley and Nehru’s generation was attempting to halt, and which they indeed did halt. Around the world, the political left is debating whether to advocate returns to pre-1980s approaches to issues such as state intervention in markets and assertive redistribution of wealth. Awareness is growing that, after the second world war, the left championed astute policies, the jettisoning of which have contributed to many of our current problems. That re-evaluation should include international relations. It should include advocacy for a return to Chifley and Nehru’s unapologetic internationalism, their emphasis on underlying socioeconomic conditions and human needs in the hard interests of global stability, and their willingness to make diplomatic concessions and compromises.

As British ministers have pursued a “new” Commonwealth, however, they have instead indicated a nostalgia for the old Empire. Trade secretary Liam Fox has used the phrase “Empire 2.0.” Foreign secretary Boris Johnson has demeaned several races in ways reminiscent of colonial stereotypes and suggested India was better for the Raj. Britain’s refusal to apologise for its colonial past epitomises not only denial about past inequities, but also disregard for the sentiments of the societies demanding such apologies.

Seventy years ago, Chifley was clear-eyed about the excesses of British imperialism; he also knew any attempt to resurrect the old British Empire in Asia was doomed to failure. Those insights equipped him to productively contribute to revising the Commonwealth. A similar clarity — realism about what a Commonwealth can achieve, avoiding nostalgia for a world that is gone forever — is needed now. What is also needed is a rediscovered sense of sobriety, a sense of the stakes at play. Contrasts with Nehru and Chifley offer themselves here too. As Janan Ganesh recently argued in the Financial Times, along with Empire nostalgia there is, within the British Conservative Party, a “frivolity,” “breeziness” and “complacency” caused by fading memories of true global crisis.

But modern Britain’s capacity to lead any process of Commonwealth re-engagement and reform is increasingly dubious. The risk that it will bring self-defeating attitudes to remaking the organisation is indicated, ironically, by the very impetus for the sudden attention to it: the decision to leave the European Union, indicative of chauvinistic rather than cooperative approaches to diplomacy, zero-sum rather than mutual-gain attitudes to world affairs. Commonwealth countries other than Britain might now usefully take the initiative.

In 1949, Nehru was facing his own decision on whether to leave what he considered a frequently irritating but still visibly useful international body. In deciding to remain, and work to improve the Commonwealth instead, he said: “In the world today… where there are so many disruptive forces at work… where we are often at the verge of war… it is better to keep a cooperative association going… than break it.” ●

This essay appears in Griffith Review 59: Commonwealth Now.