The young man outside the city station is staring at the pavement as if he’s hiding from the very people whose help he needs. I pause, drop a few coins in his upturned cap and say I hope he has a good day. Empty words, when you stop to think about it, but he looks up at me and seems to brighten at this moment of human contact. From his wispy beard to his bony frame he looks fragile, as if he could easily break. I guess he is about the same age as my twenty-year-old son. I bury the thought and rush off to catch my train.

Like me, residents of Australia’s inner suburbs witness homelessness every day. But rough sleepers huddled in doorways or crouching behind cardboard signs are just the visible part of a much bigger problem. We don’t see people couch surfing, sleeping in their cars, or holed up in caravan parks, rooming houses and motels.

When we do come across someone on the street, we often agonise about the right thing to do. If I give money, will it just go on booze or drugs? Should I give food instead? Should I offer to buy this person a coffee or just say a friendly word? Should I walk on and console myself that I donate regularly to a local charity?

I have no definitive answers to those questions, but I suspect that they are the wrong place to start thinking about the problem. Surely the fundamental issue is this: in a country that has enjoyed the longest run of uninterrupted economic growth in history, why is there any homelessness at all?

“There are no rough sleepers in Finland,” says Juha Kaakinen, chief executive of Finland’s fourth-largest landlord, the not-for-profit Y-Foundation. “You don’t see people sleeping on the streets.” It was Kaakinen who led Finland’s successful national program to reduce homelessness. Launched in 2008, it aimed to halve the rate of long-term homelessness in four years, focusing not only on rough sleepers but also on people living in insecure and temporary accommodation. “People in shelters and hostels are still homeless,” he reminds me when we meet at the National Homelessness Conference in Melbourne.

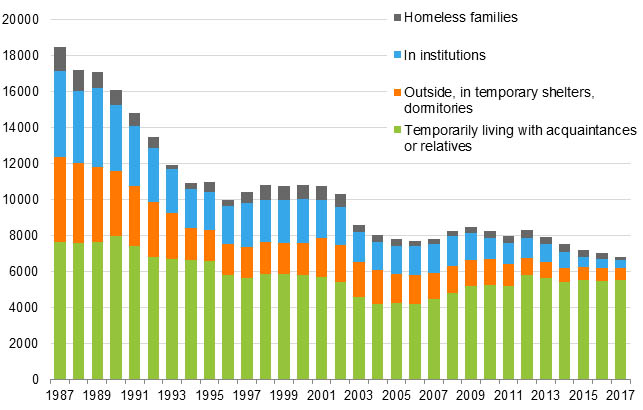

As a new report by a federation of homelessness agencies shows, Finland is the only country in Europe in which homelessness declined over the past decade. Official data puts the number of homeless people at 7112 in 2017. Among them were only 214 families, down by a third on the previous year’s figure. “There are no homeless families with children,” says Kaakinen, “or if they are it is an extremely temporary condition.” As the chart shows, the vast majority of the remaining homeless — 84 per cent — are staying with friends and relatives. Only a tiny number sleep out or live in refuges or other temporary accommodation.

On trend: homelessness in Finland 1987–2017

With its population of 5.5 million, Finland’s homelessness rate is thirteen people for every 10,000 residents. At the 2016 Census, the equivalent rate in Australia was nearly four times higher, at fifty per 10,000 residents.

How did the Finnish miracle come about? The answer is beguilingly simple: the country provided at-risk people with a secure and permanent place to live and made sure that they could afford to pay full market rent. In practice, this involved closing down most emergency shelters and boarding houses or converting them into permanent dwellings. Kaakinen says Helsinki’s last big shelter, which was run by the Salvation Army, closed in 2010 and has now been turned into eighty-one independent living apartments with onsite support services.

This might seem counterintuitive, but, as Kaakinen says, homeless people can end up getting stuck in such supposedly short-term lodgings.

By way of illustration, he tells me about a new state-of-the-art shelter for homeless people he helped develop in Helsinki in the 1980s. “Each room could accommodate two men and had a fridge,” he says. “We thought this was really top of the game. It was meant to be a temporary solution for a harsh winter, but it lasted twenty years. When we demolished it, it was the worst place. That’s what happens with temporary solutions: they become permanent.”

Having recently spent a week watching staff at work at Frontyard Youth Services in inner-city Melbourne, I could see what Kaakinen was getting at. In Victoria, as in many parts of Australia, support to overcome homelessness is generally conceived as a three-step process from crisis accommodation, through temporary housing to permanent lodgings. The theory is logical, but in practice people get stuck at chronic bottlenecks every step of the way.

Step one: After seeking help at a place like Frontyard, you get put up in a refuge. But with more than 6000 young people experiencing some kind of homelessness in Victoria, the 110 beds in the state’s fifteen youth refuges are already occupied. Doing their daily ring-around, members of Frontyard’s housing team are lucky if even one or two of these beds has become vacant. So young people often end up in backpacker hostels or back out on the street.

Step two: If you finally secure a bed in a refuge, you are not generally supposed to stay for more than six to eight weeks, at which point you move to transitional housing, where rent is capped at 25 per cent of your income. Here again, the shortage of places is extreme, particularly in the most urgently needed category of one-bedroom dwellings. As a result, a six- to eight-week stay in a refuge can easily stretch to six to eight months.

Step three: After a year, or maybe two, of getting on top of things in transitional housing, you are ready to live independently. But then you encounter another acute shortage, this time of affordable private rental housing. Anglicare’s national affordability snapshot of more than 67,000 dwellings found fewer than 3 per cent matched the budget of a single person earning the minimum wage. For an unemployed person on the Newstart allowance, only three properties across the entire country were affordable; needless to say, none of them was in a major city.

Outside the private market, the only option is social housing, which is afflicted by intractable waiting lists. A recent parliamentary inquiry found that the new Victorian Housing Register (which supposedly “makes applying for housing easy”) is clogged with 37,000 applications representing more than 82,000 people (roughly 57,000 adults and 25,000 children). There are similar waiting lists in other parts of Australia.

“Without sufficient housing you have to build systems to compensate for the lack of the real thing,” says Juha Kaakinen. “If there’s not a big enough supply of affordable housing, then it’s wise to produce more of it.” His logic is compelling. Even if the Finnish model can’t be transplanted wholesale to Australia, we can learn a great deal from it.

Finland’s success in cutting long-term homelessness and all but eradicating rough sleeping is often described as a Housing First approach. Essentially, it involves meeting a person’s need for safe and secure housing before attempting to solve other deep-seated challenges like physical or mental illness, substance abuse, unemployment or poverty.

Housing First developed as an alternative to the established “staircase” model of assistance, widely applied in Australia, which encourages homeless people to proceed through a sequence of treatment steps to reach housing readiness. Interventions like psychiatric care or a stint in a detox clinic are intended to prepare a person for living independently and sustaining a long-term tenancy. But many people, especially those who have chronic problems, find getting to the top of the staircase overwhelmingly challenging. They might get kicked out of emergency accommodation or transitional housing for getting drunk, using drugs, losing their temper or failing to attend treatment, for instance, and then tumble back down the staircase into homelessness. If one step proves beyond them, secure housing can remain permanently out of reach.

Staircase services run the risk of setting “unattainable standards,” writes Nicholas Pleace, director of the Centre for Housing Policy at the University of York, in a guide to Housing First policies in Europe. Although they’re fallible human beings like the rest of us, service users can be expected to behave like perfect citizens.

Housing First reverses the staircase model by providing secure housing up-front and not taking it away after perceived behavioural lapses. Support services are offered alongside housing, in the belief that people are more likely to successfully tackle other issues if they don’t have to worry about finding a place to sleep for the night.

Australia has its own experience with Housing First strategies, dating back more than a decade. Adelaide was the first Australian city to adopt the model, when the initial Common Ground project opened in Franklin Street in 2008. Similar projects followed in other cities, helping to fundamentally improve individual lives.

Nicholas Pleace, who was also in Melbourne for the National Homelessness Conference, says Housing First has worked wherever it’s been deployed in Europe, from tiny pilot projects held together with string in Britain, Sweden and Italy to long-term trials in France and fully fledged government programs in Denmark and Finland.

What does that success look like? “There is strong evidence that Housing First works in terms of keeping a roof over the heads of people who previously experienced chronic homelessness,” says Pleace. “Less can be said with certainty about improvements in mental and physical health, reduced drug and alcohol use or social integration.”

Housing First primarily targets people with high and complex needs. They are repeat users of overnight shelters and hospital emergency departments, and often have repeated interactions with the police and the courts, including cycling in and out of prison. “These people are sometimes referred to as ‘frequent flyers,’” says Pleace, wincing slightly at the metaphor. By reducing the rate of frequent flying, Housing First can theoretically save public money, even if chronic drug use or mental illness persist.

Data presented to the conference by Juha Kaakinen shows that in Finland, the investment in housing and supporting a homeless person pays itself back in less than seven years. A reduction in the use of specialist health services and institutional care generates savings of approximately €15,000 (A$24,000) per person per year.

In Australia, the second phase of the Journey to Social Inclusion, or J2SI, project at Sacred Heart Mission in Melbourne has yielded interim results that point in the same direction. Like other Housing First projects, J2SI uses permanent housing as “a stable base from which to address individuals’ non-housing issues.” After twelve months, J2SI participants are far more likely to be housed than those receiving standard support, and far less likely to spend nights in hospital or drug and alcohol rehabilitation facilities. Although the sample is small and needs to be treated carefully, average annual health costs for the J2SI participants fell by more than $15,000 while costs rose for those receiving conventional support.

But Pleace cautions that cost savings can’t be assumed, because outcomes depend on exactly who is getting help. “Housing First doesn’t necessarily generate cost savings because not all rough sleepers are a cost to the state,” he says. “Some are very low cost to leave on the street. All they need is a blanket and a bowl of soup.”

What is clear is that stabilising housing — and so averting a descent into homelessness — is more cost-effective than implementing Housing First after people end up on the streets. It is better and cheaper to prevent the tumble and the crash than to try to put the pieces back together again.

People usually have to resort to unstable housing after illness, relationship breakdown, family violence, unemployment or other life shocks. The impact of such events is felt most keenly by those with low incomes and few assets, especially when housing costs are high. Marah Curtis from the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin–Madison says it’s not just the level of income that matters but also its regularity: if you compare two households with the same annual income — one steady, the other fluctuating— then the first household will generally have better housing outcomes than the second.

A corollary of Curtis’s research is that small, timely infusions of financial support can prevent a descent into homelessness. “Markets go up and down,” she told the homelessness conference in Melbourne. “We have to insure people against that process.”

One criticism levelled at Housing First is that it comes too late — that it is the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, rather than the fence at the top.

But Juha Kaakinen insists that this is not true in Finland, where Housing First is just one component of a comprehensive national strategy on housing and homelessness. Finnish social workers are trained as housing advocates, and one of their main tasks is to help vulnerable people to maintain a tenancy. More important still is providing affordable housing. “Increasing the affordable social housing supply is the best means to solve and prevent homelessness,” says Kaakinen.

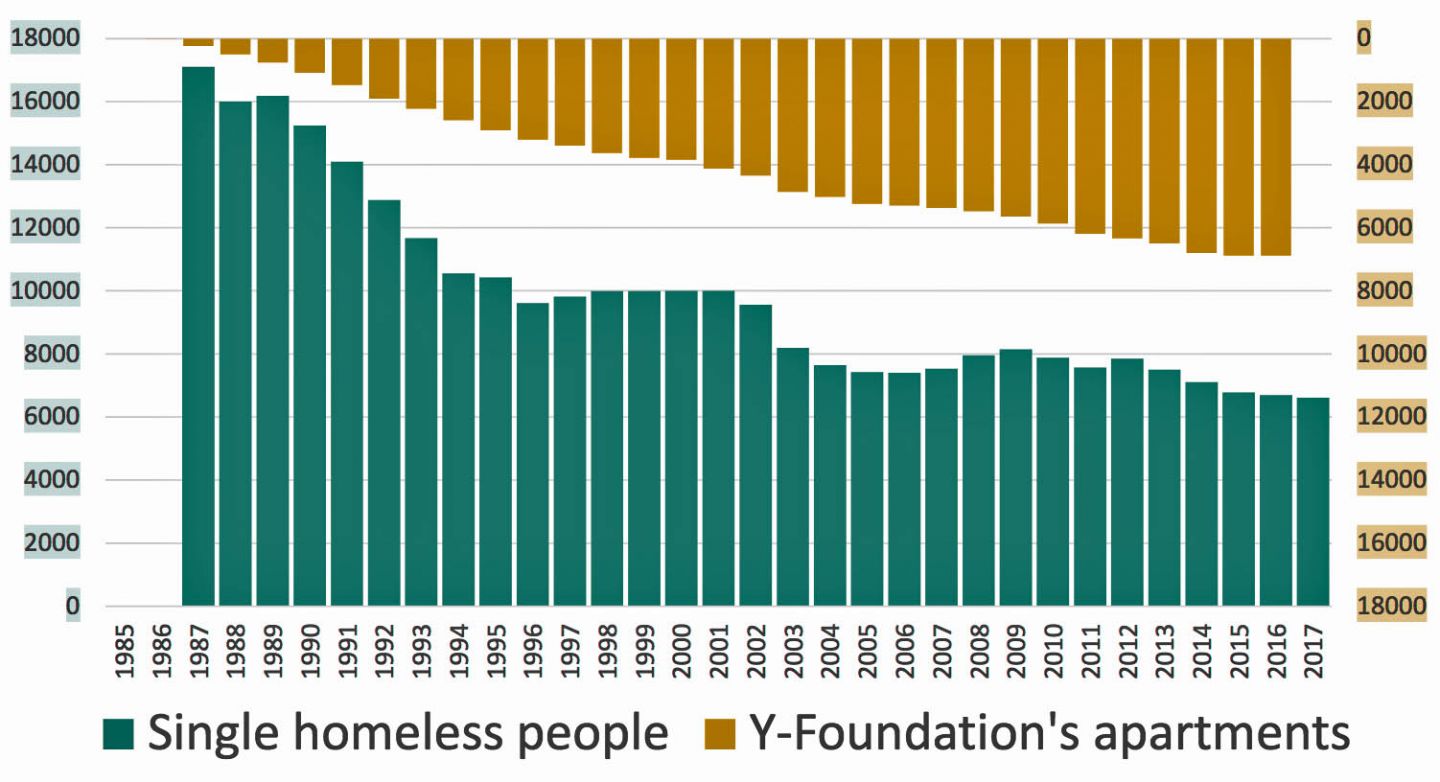

He shows a chart that provides a compelling illustration of what he means: as the number of Y-Foundation’s affordable apartments increases, homelessness falls.

Bridging the gap: affordable apartment supply and homelessness in Finland

Source: Juha Kaakinen, “Housing First and Ending Homelessness in Finland” National Homelessness Conference Melbourne, August 2018.

Australia’s own recent history accords with Kaakinen’s argument. Kate Colvin from Everybody’s Home, a campaign for a fairer housing system, told the national conference that after Kevin Rudd implemented the National Rental Affordability Scheme and injected $500 million into affordable housing in response to the global financial crisis, the supply of social housing grew, rough sleeping declined, and emergency presentations by homeless people fell. Without sustained effort, though, these gains were short-lived.

Housing First strategies can’t be divorced from their broader social context. Chronic homelessness is far more widespread in the United States than in northern Europe because of the far less comprehensive American welfare system. There, homelessness can be triggered by poverty alone, whereas in countries like Denmark and Finland it is far more likely to arise from a convergence of multiple challenges in a person’s life. So, while Denmark and Finland are dealing with a far smaller problem overall, the people who end up homeless are likely to have particularly severe problems and high needs.

In the United States, Housing First projects can end up as safe but isolated islands within the broad sea of government indifference. Nicholas Pleace calls it a “welfare state in miniature model.” In Finland, by contrast, Housing First strategies are integrated into a fully fledged welfare system, including universal healthcare and an extensive supply of social housing. People assisted by Housing First have access to the same high-quality support services as everyone else.

Kaakinen sees risks in developing small-scale Housing First projects without a comprehensive strategy to tackle homelessness. “You end up creating a priority service for a very small group of homeless people,” he says. “That’s not solving the issue.” He also thinks that a small-scale effort can pose ethical problems by delivering two levels of housing support. “There is the normal service and there is the good service,” he says. Nor does he see any need for more Housing First experiments or pilots: “We know what works.”

Australia probably sits closer to Finland on the welfare spectrum but closer to the United States when it comes to piecemeal efforts to tackle homelessness. We enjoy universal healthcare, but most government benefits are paid at a low level and there is very little social housing. In Finland, social housing accounts for about 13 per cent of all dwellings; in Australia, it’s a little more than 4 per cent. There are other differences, too. While neither country is a nation of renters — about 70 per cent of Finnish housing is owner-occupied, a proportion similar to Australia’s — rental agreements in Finland are generally permanent, whereas Australian rentals tend to be short-term, making it easy for landlords to eject tenants with little notice.

Affordable housing is largely built by the private sector in Finland, but the government provides long-term low-interest loans to developers on a 5 per cent deposit and guarantees their returns with a housing benefit that can cover up to 80 per cent of full market rent. The equivalent payment in Australia, Commonwealth Rent Assistance, is capped at a maximum rate of $67.40 per week for single people living alone, regardless of how much rent they pay.

What is more, social housing in Finland is generally built on publicly owned land. Local governments in Finland tend to control much larger tracts of urban land than their counterparts in Australia. Kaakinen tells me that the City of Helsinki owns about half the land in the capital, which gives it a very strong hand in planning decisions. A fifth of the dwellings in all new residential developments must be set aside for social housing, and authorities use their rental guarantee to ensure that new social housing meets high standards of design and energy efficiency. “You can’t tell the difference between public and private housing in Finland,” says Kaakinen. In Australia, where publicly owned land is split across three levels of government, local authorities don’t have the same leverage. Still, as new research shows, our cities have many suitable parcels of unused and “lazy” public land that could be used for new dwellings.

Building a large supply of affordable housing has other benefits. It helps to contain rents in the private market and smooths boom-and-bust cycles in the residential construction industry. “When the economy is booming, construction companies are not interested in building social housing,” says Kaakinen. “But they have a sudden increase in social consciousness when the economy slows, and there is a lot of attention when you put out a tender.”

In the absence of more substantial subsidies or stronger planning regimes, Australia’s private developers have no incentive or requirement to build low-income rental housing. Kaakinen says it’s in the national interest to provide more affordable housing as basic social infrastructure, but this won’t happen without coherent policy and concerted effort. “It’s really wishful thinking to think that the private market would solve homelessness or housing issues,” he says. “That’s a completely crazy idea.” He argues that the logic of capitalism works against a balance between housing supply and housing demand because housing shortages push up prices and generate higher returns.

Kaakinen starts from the principle that secure and adequate housing should be a social right but says this right cannot be seen in isolation from other economic and social policy. He’s critical of Australian tax policies that make housing the most secure and profitable place to store wealth: “If all the money that people invest in housing was used for other investments, then that would generate greater productivity.”

Halfway to the station platform, I realise there might be something else I could share with the young man on the pavement outside — information. I stop rushing for my train, go back and ask if he knows about Frontyard and the services it provides. He tells me he does, that he’s been there and is on a waiting list for accommodation. We chat for a while longer and his spirits seem to lift. He’s hopeful that things are starting to look up.

“I’ve got my instrument back with me now,” he says, patting the guitar tucked behind the backpack and rolled-up sleeping bag he’s leaning on. “I’m saving up for my busker’s licence, so I should be working again before too long.” I tell him I look forward to hearing him singing on the streets of Melbourne soon. I hope I do, and I hope he finds a place to live, but until we deal with the fundamental lack of affordable rental housing, the odds are stacked against him.

We need to stop regarding homelessness as inevitable and to name it for what it is — a failure of policy and politics that can be overcome. Finland shows that a national strategy to increase the supply of affordable housing can work. Without that, Housing First approaches won’t make a Finnish-sized dent in the problem. ●