IT’S JUST over a hundred years since the Commonwealth parliament took a train to Queenscliff. They didn’t just want innovation; they were looking for magic.

It was 1906, a decade after a twenty-two-year-old Italian had been granted a patent for “wireless telegraphy.” Experimenting at his family’s home in Bologna, Guglielmo Marconi had worked out how to transmit Morse code signals across short distances without wires.

People had been doing this with wires for half a century. Doing it without wires was magic. When Marconi claimed to have transmitted a signal across the Atlantic in December 1901, many refused to believe him. They thought nature might have played tricks with his equipment, or bravado with his results. But the man who a few years later shared the Nobel Prize in Physics was not deceived.

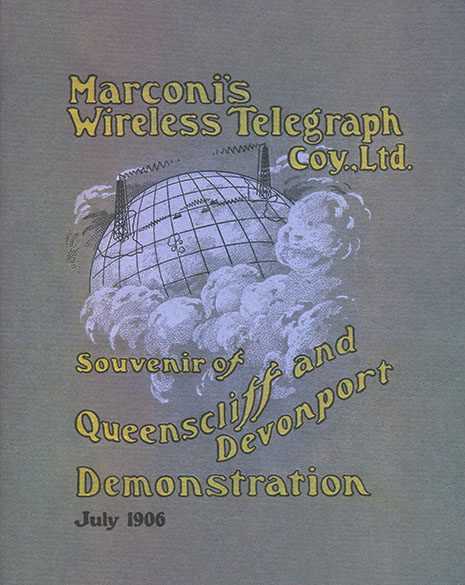

By 1906, when the Commonwealth parliament took a train to Queenscliff, the Italian was a global celebrity. Though his London-based company had still not turned a profit, it had a global network of subsidiaries and affiliates and some prestigious customers – the Royal Navy, Lloyd’s and Cunard.

Marconi was not going to be in Queenscliff himself. In his place came a representative, Captain Louis Walker, and two technical assistants. Walker spent a year-and-a-half in Australia trying to sell three things: the idea of wireless, the Marconi wireless system, and shares in Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company. He had very little success.

The timing seemed good. The Commonwealth parliament had passed the first Wireless Telegraphy Act the previous year, 1905. A demonstration of wireless communication across Bass Strait seemed a politically savvy pitch to the politicians of the young Australian federation. The distance, around 200 miles, was comfortably within the capacity of Marconi’s technology by then.

The twelfth of July was supposed to be a sitting day for the House of Representatives, which met in Melbourne. But three-quarters of the members and all but two of the cabinet told Prime Minister Alfred Deakin they were accepting Captain Walker’s invitation to attend the demonstration. So much for the new Australian parliamentary democracy. Politicians prefer a new communications infrastructure project any day.

The House adjourned for most of the day, though not without dissent. The member for Corangamite complained that the invitation was “merely to attend a picnic.” There had already been “a great many picnics” in the five-year life of the national parliament, he said. And this one was “a picnic to support a monopoly” – the Marconi system, which the company was trying to make the sole world wireless standard. “Worse than that,” he said, “it is a foreign monopoly.”

What the member for Corangamite thought particularly offensive was that, to make way for the Marconi picnic, parliament had to adjourn debate on the Australian Industries Preservation Bill. This “Anti-Combine Bill” was based on the Sherman anti-trust legislation, passed in the United States in 1890, which outlawed restrictive trade practices. It was eventually passed by the Australian parliament, but the High Court interpreted it so narrowly in a case a few years later that Australia was left without effective trade practices law until the 1970s.

So debate on the Australian Industries Preservation Bill was set aside and a specially organised train took the politicians from Melbourne to Queenscliff station. The governor-general, the prime minister and the governor of Victoria were the stars of a large and luminous cast. They were greeted by 200 schoolchildren who sang the national anthem, a small price to pay for the half-day holiday they had been granted.

Cobb and Co coaches took the party past the flags, strung between the post office and the Grand Hotel, to The Springs, just before Point Lonsdale. There, the Age thought there was “little for the eye to see – nothing of ostentatious display.” In fact, there were two masts 162 feet high. Wires strung between them provided the aerial, which was connected by cable to equipment housed in three buildings.

The 250 guests were treated to a luncheon and speeches. Prime Minister Deakin joked that, since the Anti-Combine Bill had not yet passed, he had entered into a conspiracy with the Victorian attorney-general to replace the toast to parliament with one to the success of Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company.

Contemplating future uses of the technology, the Victorian attorney-general favoured what he called pocket Marconi installations. These devices, he imagined, could be used to transmit photographs to the wives of politicians, letting them know where their husbands were. Deakin thought federal members would have nothing to fear from such mobile applications, though he was less confident about the members of the Victorian parliament.

Governor-General Northcote worried that wireless may make it harder for him to travel beyond the control of the prime minister.

As the cigars arrived, the exchange of official messages between the Point Lonsdale and Devonport stations began. Deakin sent a message to the People of Tasmania: “Australia tirelessly pursuing her great distances by rail and wire, to-day enlists the waves of the ether in perfecting the union between her people in Tasmania and upon the mainland.” Senator Keating – no relation, a member of the Liberal Party and, like Tony Abbott, a graduate of St Ignatius’ College, Riverview, in Sydney – also emphasised the federal theme: “We narrow the straits as we call across them.”

The Tasmanian governor did not miss his moment, reciprocating the mainland’s greetings on behalf of the “small and beautiful sister, by whom Victoria was founded.” He expressed the hope that the wireless experiment “may accelerate the date at which this state’s contribution towards cable subsidies can be diminished.” The Blame Game would be over soon.

Postmaster-General Chapman – the Stephen Conroy of the day – told the press of Tasmania: “No limits can be set to the beneficent influence of journalism now that the atmosphere has, at the bidding of genius, become its servant.” Somehow, I just can’t hear Senator Conroy expressing that sentiment.

Across Bass Strait in Devonport, things were less rosy. Ministers in the Tasmanian government couldn’t attend the demonstration because the government was facing a no-confidence motion in Hobart. It took forty minutes to get a reply from the governor of Tasmania because there was a bit of a backhaul problem. The wireless messages in Devonport had to be written down and sent by bicycle and ferry to the nearby post office, where they were relayed by cable to Hobart.

Marconi’s Captain Walker got a sheaf of correspondence from aspirant innovators looking for jobs with Marconi’s new medium. One man from the Victorian Railways Audit Office explained that he was a strict teetotaller with nearly four years’ experience as a warder in the Yarra Bend Asylum. He said he was “quick at picking up anything in electricity or machinery.”

Another, from St James, on the railway line between Benalla and Yarrawonga, admitted he hailed from a mere country town, but it was, he said, the home of Jas Carruthers, the Inventor of “Carruthers Electrical Clock… a great thing nearly as great as Marconi’s invention, but they won’t put it on the market I don’t know why.”

Captain Walker helped to sell the idea of wireless communications, but he failed to sell either the Marconi system or shares in Marconi’s companies. The government placed £10,000 on the estimates for a chain of coastal wireless stations, but it had no clear plan for how to spend it. It insisted there must be an open tender for any wireless stations it decided to establish. As to the chances of selling Marconi shares in Australia, Walker said “although there are a large number of rich men, they would prefer to invest their money in things they understand, and they would regard this as rather too speculative.”

Six months after the demonstration, it was clear that Australian communications policy had hit a roadblock. No decisions would be made about wireless in Australasia before the Colonial Conference in London the following year. Walker booked a passage home and, with his technical team, arranged for the storage of the demonstration equipment. Four years later, Marconi’s new Australasian representative had to break in through the window to collect it.

Walker told the secretary to the Postmaster-General’s Department that he feared Australia’s delays would “not be considered by the Public here or the outside world as in keeping with the splendid progressive traditions of the Australian Colonies.” He was frank about the failure of his trip, but he felt the year-and-a-half was not completely wasted. At the very least, he said “if I have failed to obtain a contract by my presence and work here, I have certainly made it very difficult for anybody else to…”

Australia eventually got a national wireless network – an NWN – but not for another five years, once a Labor government, led by a Queenslander, Andrew Fisher, was in office. The NWN was established by the government, not the private sector. The first wireless station was in Melbourne, and it didn’t use Marconi’s technology. The Italian magician responded in Australia as he did around the world, by commencing legal action against the Commonwealth alleging infringement of his patents.

Marconi’s company got a court order allowing it to enter the government stations to inspect the technology, but before the case could be decided the government changed. Joseph Cook’s incoming Liberal administration made a large payment to the company and the matter was settled.

Then the government changed again. The Queenslander was back in charge, though not for long. Brought down from within his own party, he resigned and headed off to an overseas post.

I could tell you a long story about Australian telecommunications, but it may sound like a short story told many times. •

Jock Given works at Swinburne University’s Institute for Social Research. He is currently researching broadband plans in Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Alberta, Canada in conjunction with Catherine Middleton from Ryerson University, Toronto. The project is supported by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

This is an edited version of a talk given at the 75th anniversary dinner of the Telecommunications Journal of Australia in Melbourne on 2 August. It draws on material held in the Marconi Archive at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford and in the Mitchell Library in Sydney. A longer version, with references, will be published in the journal’s November issue.

A cairn beside the sports field near Point Lonsdale now marks the spot where the Parliament went for the wireless demonstration. One of the original Morse code transmissions across Bass Strait was re-enacted at a centenary celebration in 2006 attended by the governor of Victoria, local politicians, residents and schoolchildren.