On America’s election day, three questions dominate. Will Joe Biden turn his polling majority into victory? When will we know? And how likely are Donald Trump and the Republicans to further sabotage the democratic process?

While this campaign has had many twists and turns, and was full of Trump’s customary outrages and baseless allegations, the headline-grabbing dramas stand in sharp contrast to the remarkable stability of the polls. The leading poll aggregator FiveThirtyEight has had Biden leading by a very clear margin since campaigning began. In the five months since the beginning of June, the smallest the gap has been was on 16 September, when it was “only” 6.6 percentage points. On Monday the figure was 8.6.

The margin calculated by the other major poll aggregator, RealClearPolitics, has always been somewhat smaller than FiveThirtyEight’s, but it too has given Biden an unusually large and broadly stable lead. Its latest figure puts Biden a normally decisive 7.2 points ahead, and its closest moment, at 5.8 points, was also in mid September.

In an ordinary election, margins like those would leave little doubt about the outcome. But the scars of 2016, when the lead in the popular vote failed to translate into an electoral college victory, have created an abundance of caution. America’s archaic electoral college system means that only ten states are pertinent to the outcome; all the others seem certain to vote the same way as they did in 2016. All ten of the relevant states went to Trump in 2016, but Biden has led in each of them at some point this year.

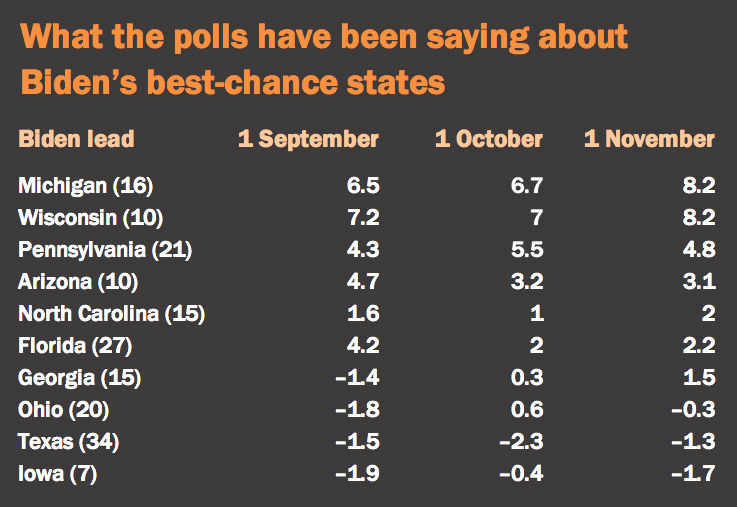

The chart below lists the ten states, with the number of electoral college votes they carry, roughly in the order they are likely to be won by Biden.

The three states at the top — Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania — are the three that Trump won by less than 1 per cent in 2016. Their narrow margins gave him his victory. They have all consistently shown Biden in the lead in recent months. Starting from his base of 232 electoral college votes — the states Clinton won in 2016 and where Biden is clearly in the lead — these three states alone would carry Biden past the crucial number of 270 to give him victory. For reasons explored below, the largest, Pennsylvania, might be the most problematic.

At the other end, Iowa is all but certain to go Republican, and as election day nears it seems to be trending further in that direction.

Interestingly, five sun-belt states — traditionally Republican — feature in the chart. Increasing numbers of college graduates and Hispanics are among their voters, and each of the states is becoming more urban.

Texas is the least likely to go to Biden. Democrats have made gains in congressional and state elections recently in Texas. In the presidential election, though, the aggregated polls have only rarely and momentarily had Biden ahead. Despite some vigorous campaigning inside the state, the Biden campaign hasn’t invested heavily there, a sign that it doesn’t think its chances are good.

Biden is ahead in the other four, in strong contrast to their recent history. Georgia last gave a Democratic candidate a majority in 1992, and Arizona in 1996 — both to the Southerner Bill Clinton. North Carolina gave Obama victory in 2008 but before that last voted Democrat in 1976 for Jimmy Carter. Florida, with its rich prize of twenty-seven electoral college votes, is always close, but in recent elections has been better for the Republicans.

In each case Biden’s margin is narrow but consistent, and none of the four states shows any sign of swinging back to Trump. So the Democrats can be cautiously hopeful of winning all of these, though the count in each is likely to be tense, and Georgia seems the least likely gain.

The last state, Ohio, is absolutely lineball. Interestingly, while FiveThirtyEight has Trump ahead by 0.3 points, RealClearPolitics has Biden ahead by 0.2 points. There has been the slightest of swings back towards Trump in the last month, and he might on balance be favoured to win.

When will we know the result?

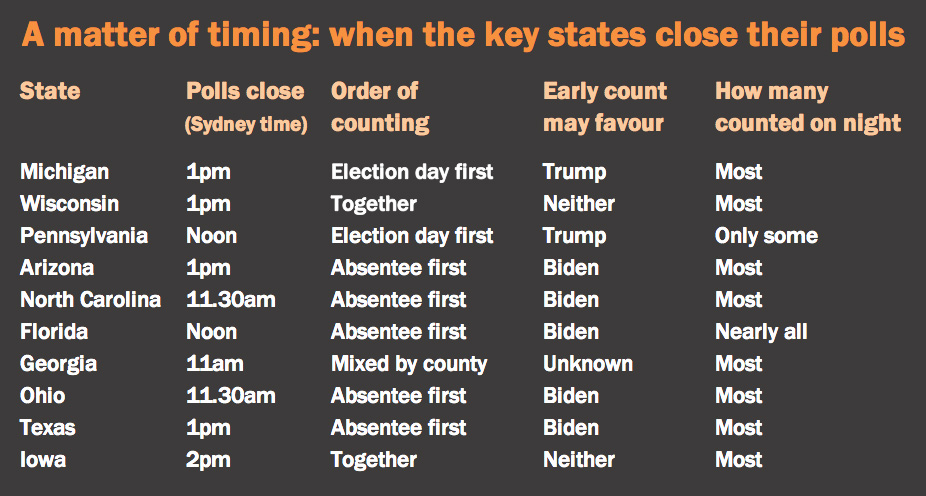

America’s East Coast time zone is sixteen hours behind Australian Eastern Summer Time, and the US West Coast is three hours further behind. The count is also governed by rules drawn up by each state and county, and the voting hours vary. The chart below shows the Australian time when each of the ten crucial states close its polls.

A major complicating factor this year is that ninety-three million early votes have been cast. The total turnout in 2016 was 136 million, with 60 per cent of votes cast on election day and the rest split evenly between early in-person voting and mail ballots.

But although the trend towards early voting is well established, it has accelerated sharply this year, mainly because of the pandemic but perhaps also out of a fear of Republican obstruction or delays and other problems on polling day. Those early votes suggest a total turnout of at least 150 million, and a higher turnout usually favours the Democrats.

Not only has there been a trend towards early voting, but the proportion of those votes sent by mail has increased most. The thirty-four million in-person early votes are greatly outnumbered by the fifty-nine million postal ballots.

Different states have different rules about the order in which votes are counted. New York, Rhode Island and Pennsylvania, for example, don’t start counting absentee ballots until the day after the election. Rather perversely, Alaska doesn’t start counting them until a week after the election. Differing rules also determine how late postal votes can be accepted, although it’s to be hoped this year that most ballots will have arrived on time.

Fortunately, most of the battleground states count early voting ballots first or at the same time as on-the-day ballots. The third and last column of the chart are based on information given by election officials in each state to the New York Times and FiveThirtyEight. Because more Democrats have opted to vote early, with Republicans more likely to vote on the day, the order in which different types of votes are counted may give a misleading early indication of the final total, as noted in the second last column.

States also have reputations for being fast or slow counters — although counting postal votes is always slower because of the extra clerical tasks involved.

When each state’s result is known depends partly on logistical arrangements but equally on how close the vote is. Florida is the only state that expects nearly all of the count to be completed on election night, but in most of the others enough of the vote will be counted to give a strong indication of the likely winner, unless it is neck and neck.

Among the first to have advanced counts will be North Carolina, Florida and Georgia. If Biden wins two of these he is headed for a strong victory; even one of them will be a good indicator.

Beyond the official count, two groups of media organisations undertake preliminary work that may give a good indication of how things will transpire. One conducts a huge number of exit polls across the nation. To avoid a misleading impression, they will need to include polling of early voters. The other group carried out a very large survey in the day or two before the vote, and will release the result on election night.

Trumpian dirty tricks

As I observed in a previous article, the United States is the only established democracy where part of one major party’s strategy is to make it difficult for likely supporters of the other side to vote. One blatant example in this election was the Republican governor of Texas decreeing that there would be only one ballot dropbox per county. This gave the Democratic stronghold of Houston just one for five million people, whereas previously it had eleven.

The bigger fear this time is that the attempted manipulation will stretch beyond election day. Already more than 300 lawsuits have been launched in forty-four states, with more likely to follow. The United States has the most litigious elections in the world and the most politicised courts in the Western world, not a reassuring formula.

Even before the election campaign proper began, Trump was saying it was rigged. He has refused to say whether he will accept the result. He has frequently charged that mail ballots will bring huge amounts of fraud, even though they are a long-established part of American voting and instances of fraud in earlier elections have been negligible.

The larger democratic risk with mailed ballots is that they are less likely to be counted. They are more prone to loss and error, and more subject to legal challenge and rejection. They can be rejected on the grounds that the signature on the ballot doesn’t match the signature on the voter registration forms. They can lack the secrecy envelope required in some states. They may arrive too late to be counted. All of these are likely to cost more Democrat votes than Republican ones. The only hope is that all this will not be on a scale that endangers the result.

Trump has said frequently in recent days that the result should be known on election night. This has no constitutional basis, but it may be his aim to claim victory on the basis of on-the-day votes and seek to sow confusion.

This is where Pennsylvania may become the Democrats’ nightmare. As noted above, Michigan and Pennsylvania count votes cast on the day first. Michigan will count early votes later in the night, and officials say they are hopeful of having the count well advanced.

Pennsylvania, on the other hand, doesn’t start counting early ballots until the following day. This raises the distinct possibility that Trump could be ahead at the close of counting on election night. He may then claim victory — depending on the count elsewhere — and mount some sort of challenge to further counting or — if he later loses Pennsylvania, as is very likely — will claim the postal votes were fraudulent.

A Biden victory is overwhelmingly likely, but no one expects Trump to go graciously. He is likely to become the first losing president in history to challenge the legitimacy of the process. The best guarantee of minimising the damage he can cause is a strong and early victory by Biden. •