The big saffron-coloured bus, driven by Narendra Modi and carrying his Bharatiya Janata Party and its associates, blew a tyre last week. At the end of counting on Saturday, the BJP’s incumbent government had lost heavily in legislative elections in the southern state of Karnataka. (The bus of course is a metaphor: bus driving is not among the many virtues ascribed to prime minister Modi.)

Karnataka is the eighth most populous state of the Indian federation. It has the largest per capita GDP of all the major states, and Bengaluru, India’s swinging IT centre, is its capital. It is the only southern state where the BJP has managed to win government.

This time the party lost forty seats and was reduced to sixty-six seats in a 224-seat house. The rival Congress party took 43 per cent of the vote, won 135 seats, and will form the next state government.

Turnout was strong, at 73 per cent of the fifty-three million eligible voters. (Only 260,000 took advantage of an endearing feature of Indian elections: every ballot paper has the option to vote for NOTA — None of the Above.)

The BJP threw everything into the campaign to retain its foothold in the south. The endlessly energised Narendra Modi, seventy-two, spent ten prime ministerial days campaigning in Karnataka and did a five-hour, twenty-five-kilometre road rally through the streets of Bengaluru and its suburbs. That may have paid off: the BJP gained seats in Bengaluru even as it was being clobbered in the rural areas around the big city.

The loss was not a complete surprise. Karnataka hasn’t returned an incumbent government for nearly forty years, and the outgoing administration was widely seen as corrupt and incompetent.

But the extent of the defeat may have surprised even the Congress party. The BJP ran a well-financed campaign fuelled by predictable attempts to keep Hindu antagonism towards Muslims on the boil. But the party pinned its hopes on what is now referred to as “the Modi magic.” It may have helped in Bengaluru, but not elsewhere.

Rahul Gandhi, the weary fifty-two-year-old national leader of the Congress party, campaigned in the state and did a walking tour a few months before the election, but his presence counted for much less than competent local leadership, a canny sense of caste configurations, and motivated party workers.

To an Australian observer, accustomed to hand-counting of ballots and Senate results sometimes taking weeks to determine, the administration of these elections was remarkably fast, efficient and fair. Voting was done on standalone voting machines, with one control unit for each of the 58,500 polling stations. Counting began Saturday morning, two days after polls closed, and the results were clear by lunchtime. The system — single ballot, first-past-the-post — makes the process simple, but the Election Commission of India continues to provide a model for the world.

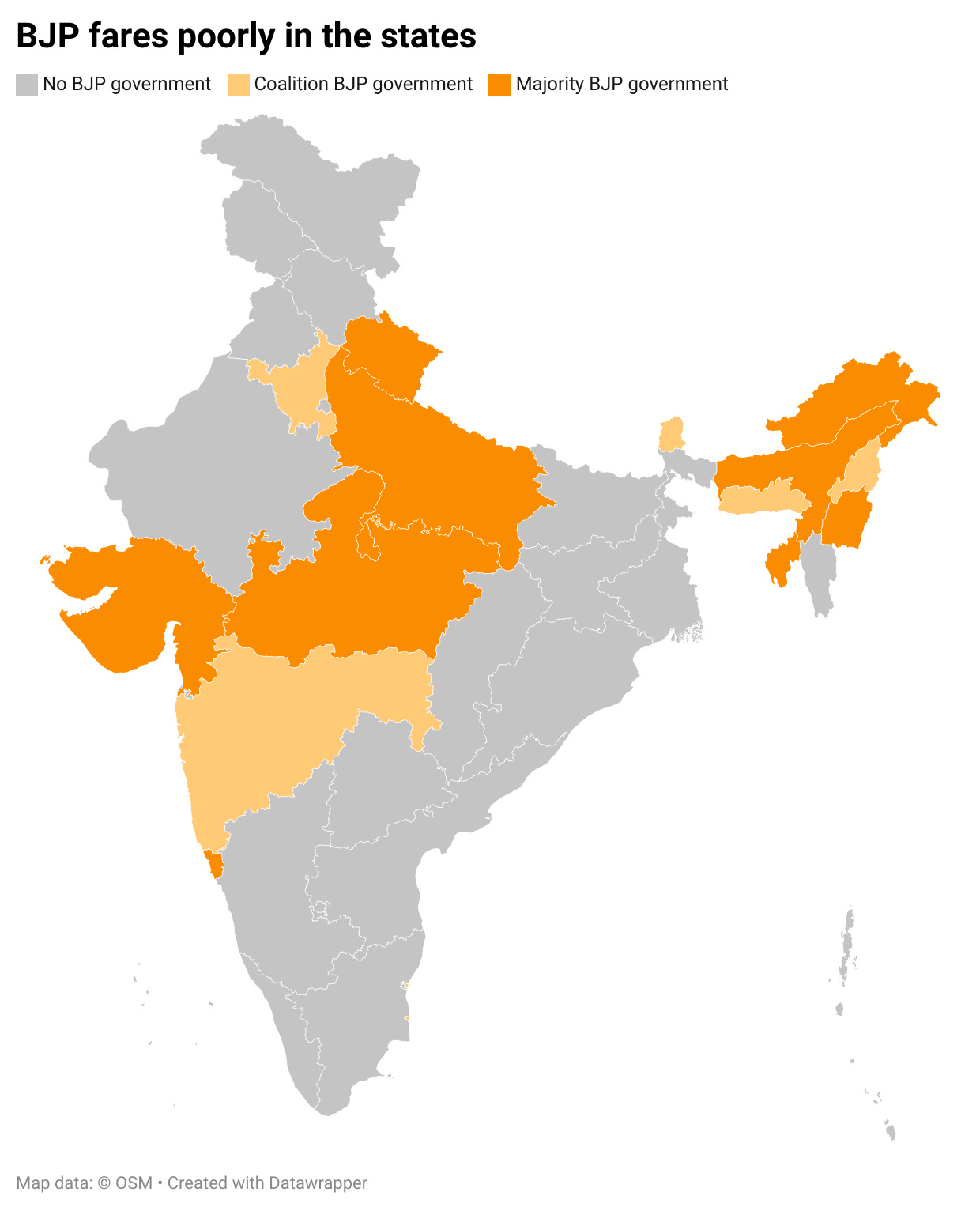

National elections are due next year, and Modi and the BJP look strong favourites to win a third term. Yet the current political map of the federation seems at odds with such domination of the national parliament. The BJP controls only eight of India’s state governments and is in coalition in six others. The other fourteen states, comprising more than half the population, are ruled by local parties or the Congress.

The map of the federation now shows a chunk of saffron BJP states stretching from western Gujarat to the vast Uttar Pradesh. There’s also saffron in the less densely populated northeast, which is a complex mix of eight smaller states. The fringes of the map — the south, east and west — have non-BJP governments.

Will the centre hold? India’s electoral map following the Karnataka result. Courtesy of Scroll.in

On the same weekend the Congress won the Karnataka election, a new political party won a parliamentary seat for the first time in a by-election. The candidate of the Aam Aadmi Party (common man’s party), founded in 2012, which already rules Punjab state, defeated the Congress, the BJP and a Sikh-based party in the industrial town of Jalandhar in Punjab.

The AAP has already won two elections for the government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi, but the BJP central government, which controls the police and appoints the lieutenant-governor, has gone out of its way to hobble it. The upstart party, however, got another win in the same week when the Indian supreme court ruled that the elected government of Delhi had the right to run Delhi without having constantly to clear decisions with the lieutenant-governor.

With national elections due next year, some analysts speculate that a coalition of the Congress and parties like the AAP could win a majority. The chances of such unity, however, seem slight. Even if it were stitched together, similar experiments in 1977 and 1989 suggest it would soon fall apart in government.

And Narendra Modi’s big orange bus has plenty of spare tyres, skilful mechanics and financial fuel. It also has a well-tried capacity to find dangerous Muslims, “urban Naxalites” (revolutionaries), “presstitutes” (journalists) and decultured pseudo-intellectuals. One of its goals, its leaders have said, is a “Congress-mukt Bharat” — a “Congress-free India” — and old BJP ideologues have hankered after a single strong central government.

The BJP and its associates may, however, run the risk of appearing to be too much of a Hindi-speaking operation, based in north India and promoting a doctrinaire version of what a proper Hindu should be. Such a conformist version of Hindu beliefs may appeal to Hindi-speaking Hindus in northern states, but it may alienate speakers of Bengali, Odia, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Marathi and Malayalam.

India’s remarkable seventy-five-year survival as a single unit has depended on its flexible federation and its democratic capacity to let regions do many things as they please, and even for the central government to carve out new states when demands are irresistible.

But the big saffron bus carrying BJP ambitions will be back on the road in a wink: there are elections in three more states due by December. •