Jason Falinski says falling rates of home ownership are “an urgent moral call for action by governments of all levels.” But does the fact he represents the outer-Sydney seat of Mackellar — first-homebuyer territory — narrow his view of the housing problem? And will it influence his role as chair of Australia’s latest inquiry into affordability?

Veteran observers question the need for another inquiry. The Financial Review’s long-time property editor Robert Harley has counted five major housing probes over the past two decades, and another — a report on the related issue of homelessness — was published just two months ago. Detailed analyses have also been published by the Reserve Bank, by Grattan Institute, Per Capita and other think tanks, and in a steady stream of research by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, or AHURI.

Yet, says Harley, “while politicians, bureaucrats and developers have championed the cause of the first homebuyer, prices have risen inexorably higher… and home ownership has slipped, particularly among twenty- to forty-year-olds.” What remains unresolved is what makes housing so expensive, and how it can be made more affordable.

One camp argues that the problem is too little supply: we simply don’t build enough houses and flats. Australia’s stratospheric house prices are the product of red tape and nimbyism, and the solution is to liberalise planning and zoning rules so that developers can get building.

The other camp thinks the core problem is excess demand, fuelled by a combination of record low interest rates, easy credit and generous tax concessions. Housing has been transformed from an essential good into a financial asset, with the search for capital gains driving prices up relentlessly. This camp thinks solutions are to be found in changed tax rules and tighter financial regulation.

Opinions don’t divide quite so neatly, of course, and some views are shared by people in both camps. Many argue, for example, that whatever else happens, governments should invest more in social housing, and swap stamp duty for a broad-based property tax. But it’s hard to see either of these sensible recommendations emerging from the inquiry.

The House of Representatives tax and revenue committee, which Falinski chairs, has been asked to report on “the contribution of tax and regulation on housing affordability and supply in Australia.” The cynic might suspect the inquiry was designed to wedge Labor over its contested housing policies in the lead-up to the next federal election. Any hope on that score was short-lived: just four days after treasurer Josh Frydenberg initiated the inquiry, the opposition dumped its pledge to change negative gearing and capital gains rules.

Expectations that the committee would produce new insights have been dampened by Falinski’s confidence that the answer to the question is already clear. In calling for submissions, he declared allegiance to one side of the housing divide, saying “the research points to limitations on land and restrictive planning laws as the major causes of shortages in supply.”

Falinski’s assumption is reflected in the framing of the inquiry. While it sets out to investigate the contribution of tax and regulation to affordability and supply, the terms of reference refer solely to the latter, as if solving the supply problem will look after affordability.

Demand doesn’t rate a mention, even though most of its drivers — interest rates, immigration levels, mortgage lending regulations, homebuilder schemes, or, indeed, tax concessions like negative gearing — are federal responsibilities. Ignoring demand means ducking responsibility, consistent with messaging by housing minister Michael Sukkar that it is up to the states and territories, which “control planning schemes and zoning,” to solve our housing woes.

Yet, as Sydney University housing researchers Nicole Gurran and Peter Phibbs point out in their submission to the inquiry, state and local governments have already significantly eased controls on residential land release and development by standardising local planning instruments, speeding up and codifying development assessments, and “depoliticising” planning decisions by using expert panels and professional assessments. Far from a lack of supply, they say, construction has reached historic highs in recent years, with more than 200,000 dwellings built every year between 2014 and 2019.

“There are more, bigger, better, dwellings per capita in Australia now compared to any point in history,” agrees economist Cameron Murray. His submission to the inquiry questions whether a further relaxation of planning and zoning controls would provide any incentive for landowners and developers to speed up new housing, since it would lower the price of their future sales. Murray argues that developers systematically engage in landbanking, “holding undeveloped sites off market to ensure they match the rate of sales that maximises their total return on assets.”

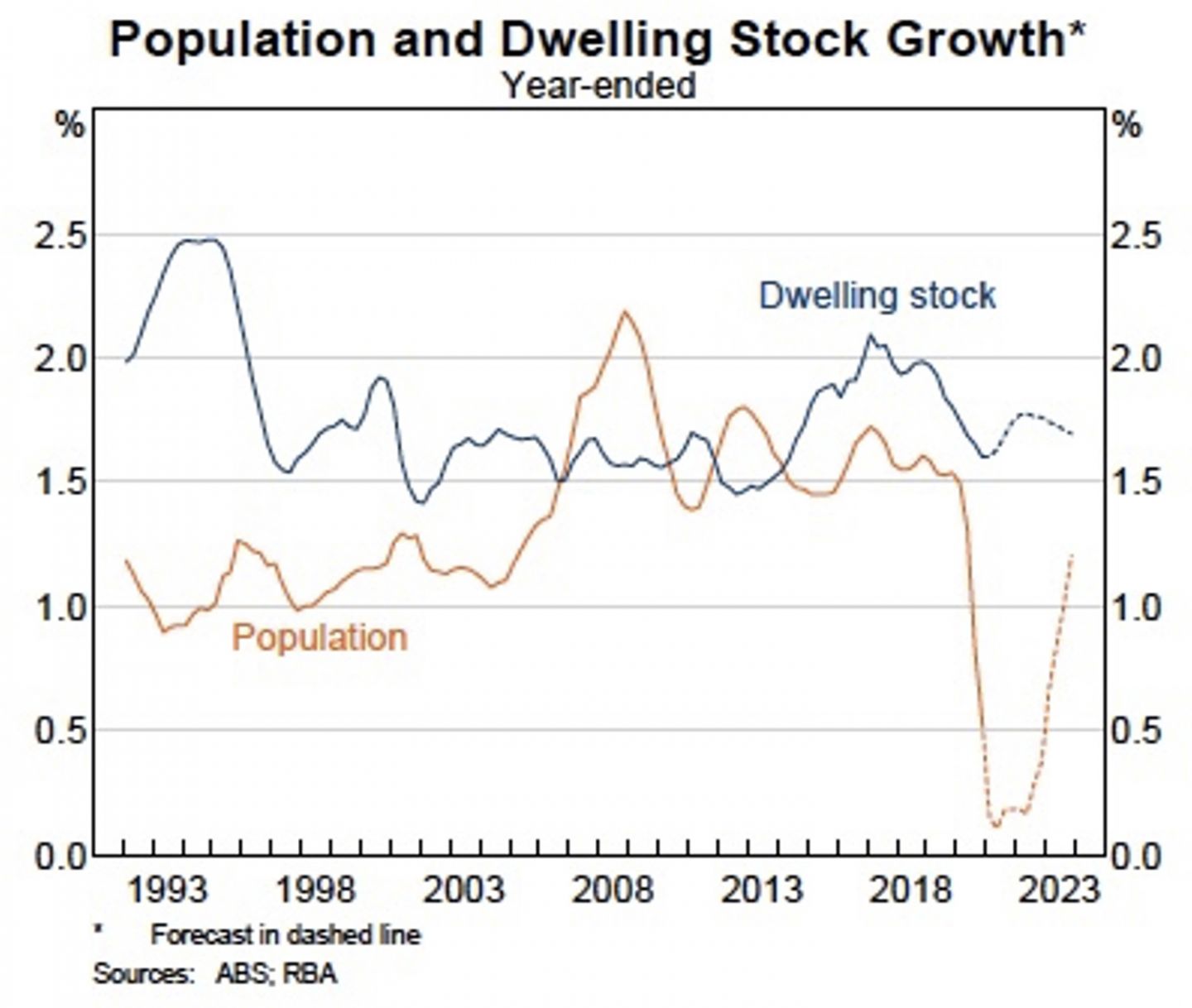

The view that the stock of dwellings has largely kept pace with population growth — and even exceeded it in recent years — is supported by Reserve Bank research, as this chart from its submission to the inquiry shows:

The sudden drop in population growth (the orange line in the chart) reflects border closures in response to Covid-19. That fall challenges another version of the supply-side argument — that prices have rocketed in recent years because house building failed to keep up with Australia’s high migration intake. In theory, flatlining immigration since early 2020 should have pushed prices back down again. Instead, with a few exceptions (such as high-rise inner-city apartments in Melbourne), the real estate market has boomed.

As the pandemic demonstrates, the relationship between population, housing supply and prices is far from straightforward.

Not everyone on the Coalition side of politics agrees with Falinski and Sukkar. Writing in the Sydney Morning Herald earlier this month, NSW planning minister Rob Stokes declared “the idea that the planning system alone can solve housing affordability” to be “ludicrous at best; wilfully negligent at worst.”

Simple maths supports his contention. As the Planning Institute of Australia points out in its submission to the inquiry, new housing only increases the total stock of dwellings in Australia by about 2 per cent each year. Because most sales and rentals involve established homes and apartments, “it is hard for additional supply to reduce prices rapidly and deeply.” Even if we doubled the volume of new housing coming onto the market — a high hurdle given constraints on labour and materials — the impact on overall prices would be relatively modest.

This is not to suggest that the problem of housing affordability isn’t urgent. It certainly is, but for rather different reasons than Jason Falinski assumes. His primary concern is with declining rates of home ownership, which he describes as “one of the building blocks of Australian society.” But the more pressing problem is the fall in rental affordability for tenants on low incomes.

We’re familiar with comparisons showing a sharp rise in house and unit prices compared with earnings in recent decades. Westpac, for example, reported in June that “dwelling prices reached seven times average annual earnings” at the end of April 2021, about double the ratio at the start of this century.

But property prices are not necessarily an accurate guide to household housing costs, which are better understood as the amount individuals or families must spend each week — usually in the form of rent or mortgage repayments — to stay in their homes. For most households, housing costs as a share of income are far more important than the price of real estate: they can’t be avoided, and they determine how much money is left to pay for other things.

Australian households can be divided into three groups of roughly equal size: tenants, mortgage holders and outright homeowners. For tenants, rents are the most important factor influencing housing costs, and they have generally risen relative to incomes. For mortgage holders, the most relevant cost factor is interest rates; these have dropped, reducing the price of servicing a mortgage, even though people have taken out bigger loans. For outright homeowners, housing costs bear no relationship to fluctuations in rents or interest rates.

This means that two-thirds of households (mortgage holders and outright homeowners) have not faced rising housing costs over the past two decades, despite escalating house prices.

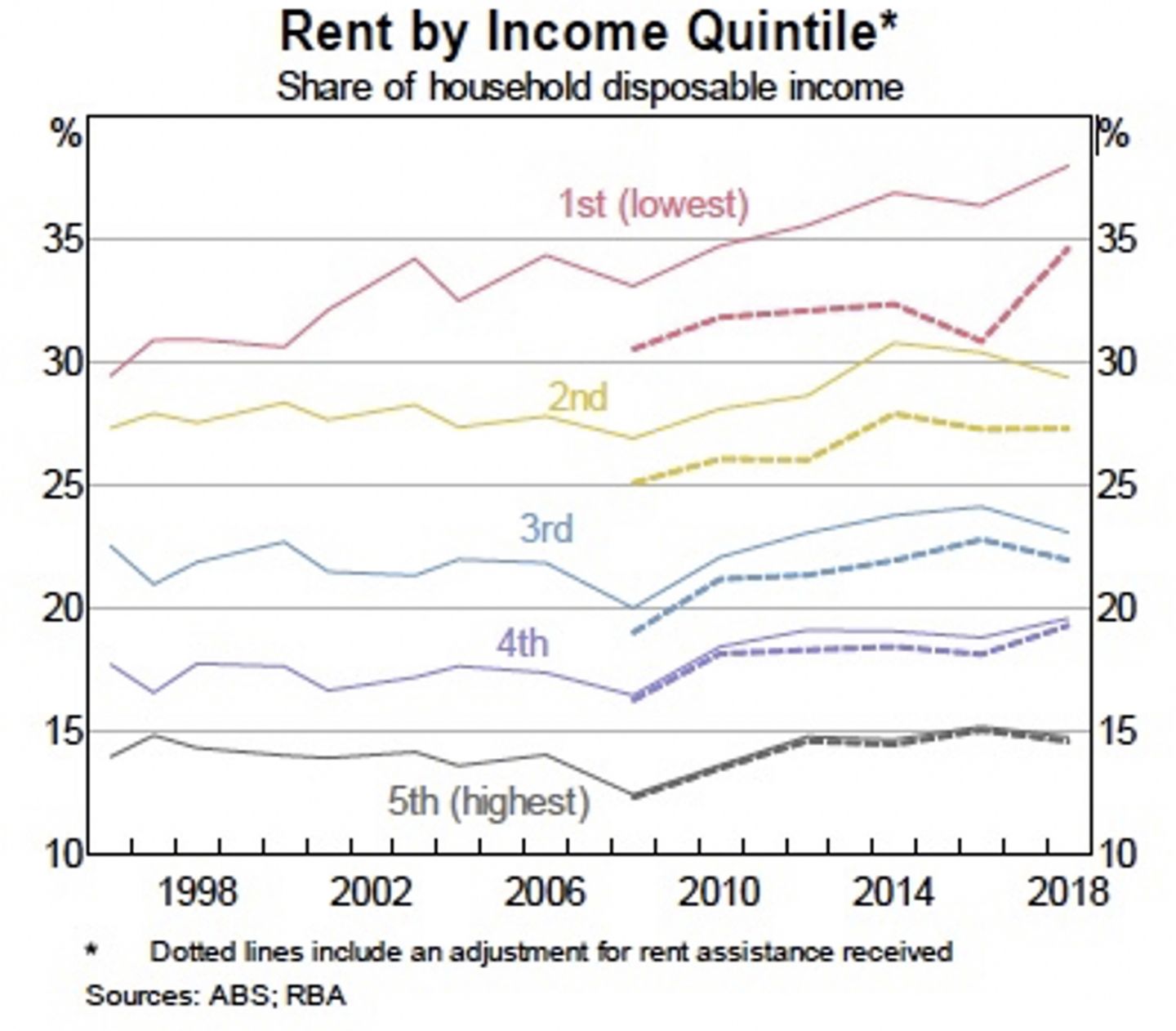

It’s a very different story for the other third — tenants — and especially for low-income tenants in the private rental market. The true nature of Australia’s housing affordability challenge, and where its impact is most acutely felt, is revealed in another chart from the Reserve Bank’s submission, which shows that for tenants in the first “quintile” (the bottom fifth of households by income), rents have risen, dramatically and unsustainably, to 38 per cent of disposable household income.

Not surprisingly, the Productivity Commission has found that half the low-income tenants in the private rental market experienced rental stress in 2017–18, spending at least 30 per cent of their disposable income (and often much more) on rent. That’s around 550,000 households — many of them families with children — that didn’t have enough money left over to pay for other essentials. And it has happened despite the $4.6 billion paid to some low-income tenants in Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

For these households, the supply problem is a lack of affordable homes to rent. Rising real estate prices do make matters worse, because they make it harder for moderate- and higher-income tenants to move to ownership. Wealthier tenants spend longer renting in the private market, out-competing low-income households for the most affordable homes with the best access to jobs and services.

In theory, a general increase in housing supply should push down the prices of houses and flats, and subsequently rents, across the board. Affordable housing would eventually filter down to low-income tenants.

But the filtering theory has at least two fundamental problems.

A general increase in overall housing supply could take a long time to filter down, with much damage done to individuals and families in the meantime. More fundamentally, though, the filtering doesn’t actually happen, because Australia’s tax structure — its preferential treatment of owners and investors — boosts demand for housing as an asset and encourages house-price inflation.

Supercharged by low interest rates, these tax settings make housing a highly attractive asset, for both owner-occupiers and investors. As researchers Blair Badcock and Andrew Beer concluded more than twenty years ago in their book Home Truths, “taxation arrangements have played an unambiguous role in the high proportion of wealth in Australia held as housing. In many respects, high-income earners would be foolish to invest elsewhere!”

In any case, if prices were to fall to the degree necessary for housing to “filter down” to the poor, that would signal a collapse on the scale experienced in the United States, Spain and Ireland during the global financial crisis.

As the Reserve Bank remarked in its submission to a 2015 parliamentary inquiry, “there are no examples internationally of large falls in nominal housing prices that have occurred other than through significant reduction in capacity to pay (e.g. recession and high unemployment).” In other words, the only sure-fire way to quickly make housing substantially cheaper is to crash the economy.

It’s not an outcome anyone would seek. But it points to the high-stakes situation that Australia finds itself in because our sustained residential property boom has dramatically increased household debt.

Just before the global financial crisis, Australia’s total household debt was estimated at $1.1 trillion, or a little over $50,000 per person. By early 2018, the figure had more than doubled to an estimated $2.466 trillion, or close to $100,000 for every person. Over the same decade, the ratio of household debt to annual household disposable income rose from about 160 per cent to around 200 per cent. The vast bulk of household debt is tied up in loans for buying homes and investment properties.

If interest rates remain low, rising household debt is not necessarily a problem. But a rise in interest rates could force a significant number of households into housing stress, with concomitant risks for major Australian major financial institutions heavily exposed to mortgage lending.

Australia’s housing system also encourages a volatile boom–bust cycle of property investment. Since construction is a major employer, this has repercussions throughout the economy. Given long lead times, developers are slow to ramp up employment in an upswing but quick to shed staff in a downturn. As the OECD has concluded, changes to the tax treatment of housing could moderate this boom–bust cycle: “Higher effective taxation of housing is associated with less severe downturns. Moreover, countries with higher taxation experience more moderate house price fluctuations and smoother residential construction cycles.”

And while the building of housing generates jobs, housing is not in and of itself a productive investment. Increased dwelling prices reflect the value of the underlying land more than the value of the dwelling. The escalation of residential property prices, and the increased borrowing necessary to finance it eat up investment funds that could potentially have been put to more productive use.

I share Jason Falinski’s concern with falling rates of home ownership, but not because I want to “restore the Australian dream for this generation and the ones that follow.” More important, in my view, is to reduce growing inequality.

With interest rates so low, the barrier to home ownership has less to do with managing a large mortgage than with saving the deposit needed to secure a mortgage in the first place. Higher education debts, superannuation contributions and a casualised labour market make it harder for the current generation of first homebuyers to assemble a deposit.

As researchers Hal Pawson, Vivienne Milligan and Judith Yates write in their book Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for System Reform, “wealth rather than income” now presents “the major stumbling block to home ownership.” Home ownership must often be facilitated by funds from parents, which are in turn enabled by existing property wealth. Homeowners beget homeowners and renters beget renters, with the risk that home ownership will become a dynastic privilege. And since the primary financial asset for most Australian households is their dwelling, the difference between owning and renting generally holds the key to whether you acquire any lifetime wealth.

Falling rates of home ownership will also increase pressure on government payments. Australia’s relatively ungenerous age pension rate is predicated on widespread home ownership keeping housing costs low in old age. But declining rates of home ownership mean this “fourth pillar” of Australia’s welfare system is crumbling as more households rent in retirement. Unless house prices can be moderated, pushing up home ownership again, the federal government will need to outlay ever greater sums on pensions and rental assistance.

Our best hope is to engineer a gradual deflation of dwelling prices or allow them to stagnate relative to inflation. Changing the tax mix to make housing a less attractive asset is arguably the best way to do this.

In the meantime, Jason Falinski’s committee could have a quick, practical impact on housing costs and rental stress by recommending the federal government increase the rate of Commonwealth Rental Assistance. As AHURI research has shown, that could be done painlessly by targeting rent assistance more accurately to those on the lowest incomes.

For the longer term, the committee could recommend that the federal government makes a substantial investment in social housing. As Nicole Gurran and Peter Phibbs write in their submission, “The most notable shift in Australian housing production over the past thirty years has been the gradual withdrawal of government involvement in land and housing development, with public sector housing completions falling as a proportion of all new housing from around 12.5 per cent in the early 1990s to around 2 per cent by 2016.”

A long-overdue national housing strategy with a time horizon of at least twenty years should fund an annual increase in supply of at least 15,000 new units of social housing to catch up with unmet demand. This is about five times what gets built now, but no more than the numbers regularly achieved in the decades after the second world war. Sometimes to go forward, we must first look back. •