What cause unites the following: Barack Obama, Xi Jinping, Angela Merkel, Julie Bishop, Bill Gates, Hillary Clinton, Christine Lagarde, Shinzō Abe, John Key, Narendra Modi and Michael Bloomberg? “An elite one” sounds right. “UN promotion of child literacy in the majority world” has a convincing feel. “No to Donald Trump” is more than plausible. But in London, in 2016, “Britain to stay in the European Union” would be the first answer on many lips.

That’s a tribute to the “Remain” camp, whose determination to win the referendum on 23 June is reflected in aggressive promotion of the views of such luminaries. What equivalents do the “Vote Leave” side have to draw on? Rupert Murdoch, John Howard, Vladimir Putin’s unlovely allies on Europe’s extremes, and indeed Donald Trump himself are about it.

For remainers, that international power list reinforces the case that the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union, or “Brexit,” would remove the country from the world’s top drawer. Few messages, after all, are better designed to strike a chord among the British. Obama’s comment on 22 April that Britain would go to “the back of the queue” on any bilateral trade deal after departing the EU was a real zinger, while Bishop (“a strong UK as part of the European Union would be in Australia’s interests”) and Lagarde (“my hunch is that [Brexit] is bound to be a negative on all fronts”) were unfussily direct.

Things don’t get any easier for leavers on the domestic front. A host of professional bodies, including the respected Institute of Fiscal Studies, estimates that substantial economic costs may follow a Brexit. (After the IFS’s report was published on 25 May, Vote Leave branded it as “a paid-up propaganda arm of the European Commission” on the grounds that it receives European Research Council funding.) Many leading businesses and professional bodies – of scientists, engineers and architects, for example – warn of negative effects in their areas. Pro-EU letters signed by dozens of writers, artists and academics fill the papers. It’s not all one way: leavers are a vigorous presence in every forum, have equal representation in broadcasting media, and receive loud (often raucous) backing from the Mail, Sun, Telegraph and Express groups. But remainers’ lead in official circles is overwhelming. In times both insecure and anti-establishment, will this lose or lure more votes?

The complicating factors multiply. As an issue, European Union membership refuses to align neatly along political lines. Voters can use a referendum to kick the government of the day. Events close to the poll, such as the release of public borrowing figures on 21 June, might shift their view. Most polls do show Remain ahead, and the betting markets lean around 70 per cent that way. Yet no one expects a repeat of the first UK-wide referendum in 1975, when 67 per cent (on a 64.5 per cent turnout) voted to stay in the then European Economic Community. Remainers fear that a low turnout, especially among younger people, will allow more motivated and older outers to pull ahead.

Ten days into the formal campaign – which began only on 23 May, though the informal one, in the manner of today’s borderless elections, has been going on for months – there is enough uncertainty to motivate both sides to the max.

The key quarrels between Remain and Vote Leave are over the economy, security and immigration. Just behind are questions of self-government, history and “who we are.” The European Union’s own wrangles over the eurozone, geopolitics, migration and extremism, and how far Britain can or should try to be insulated from them, are a constant presence. With such hard issues and high stakes, the referendum is, in its way, as existential for the future of the United Kingdom as was Scotland’s independence vote in 2014.

“Europe” has been inducing neuralgia in Britain’s collective unconscious for over six decades. Joining a trading bloc was painful enough (though the Conservative Party was in the vanguard of the attempt from the 1950s to the 1970s, while much of the Labour Party and trade unions were opposed). But later political integration has touched unceasingly on the structures of sovereignty, history and identity that undergird the psychic coherence of the British state, its political class and many citizens. Navigating these currents has been bumpy. Even in periods of comparative calm, Britain’s membership of what became the European Community and then (in 1992) the European Union has never felt completely settled. It is unlikely that the vote on 23 June will change this.

But the event is also a compelling drama of domestic politics. This is most visible in the agony of the governing Conservative Party, whose leading players – prime minister David Cameron and chancellor George Osborne – deliver ringing scripts to a cacophony from their fractured cabinet and mutinous MPs. Cameron’s decision to suspend collective cabinet responsibility for the duration, echoing the Labour prime minister Harold Wilson before that 1975 vote, thus gave the cerebral justice minister, Michael Gove, and the rumbustious former mayor of London, Boris Johnson, permission to beat the Brexit drum. The employment minister, Priti Patel, is a forceful “outer,” and Gisela Stuart, a Labour MP of German birth who was converted to the Brexit side by experience of the EU’s inner workings, has campaigned tirelessly. Indeed, most women prominent in the debate tend to be outers, at least in England.

An enduring, unresolved obsession with the European Union and its threat to national sovereignty has brought the Tories to this point. It began under Margaret Thatcher, whose derangement over the issue led to her fall in 1990, and has gripped all five Conservative leaders since. Three of them were Eurosceptics who, between 1997 and 2005, neither exorcised the ghost nor reversed the precipitous decline of the party. Cameron did both, up to a point: having enjoined the Tories to “stop banging on about Europe,” he led them into coalition government in 2010. But mid-term troubles and desertions to the United Kingdom Independence Party, or UKIP, produced revenant shrieks. In January 2013, at Bloomberg’s headquarters in London, he promised to renegotiate the UK’s membership terms and seek voters’ sanction on the outcome.

Artful dodge, fatal concession, or political sidestep? History will tell. Cameron’s larger hope was to vanquish the European spectre inside the party once and for all, and create room for a forward-looking Tory agenda free of its bewitchment. But the prime minister’s demarche had the opposite effect. The vision that had taken hold in the 1980s–90s, of Britain starting over outside the EU – as a buccaneering global entrepôt or a nativist anti-immigrant grouch (tick according to preference) – was just too enticing.

Much still depended on the election to come in 2015, which few expected the Tories to win outright. Only thus would Cameron have the power to redeem his pledge. But he did win, and in the flush of victory pitched in to a round of talks with his EU partners. Europe’s migration emergency complicated matters, as did rising populism on the continent. Next year’s elections in France and Germany began to seem even more pivotal. It was important to get a quick deal. And a reading of both the Bloomberg speech and a pre-negotiation talk at Chatham House in November 2015 leaves no doubt that Cameron wanted one.

On the latter occasion, he outlined four objectives, the most prominent being “to tackle abuses of the right to free movement, and enable us to control migration from the EU, in accordance with our election manifesto.” Although the migration crisis had frayed the Schengen Agreement on open borders (from which Britain has an opt-out), this objective hit a basalt wall of opposition from Angela Merkel and other leaders. The agreement of February 2016 contained weaker provisions than Cameron had sought in relation to in-work benefits for new EU migrants, and included guarantees that Britain would not be required to accept further integration, and that bureaucracy would be constrained, competitiveness encouraged and the obligation to help bail out troubled EU economies limited.

This post-heroic drama in classic EU style, more Don Quixote than Henry V, gave ideological outers another chance to parade their A-to-B gamut of postures: scorn, grievance, self-righteousness, vindication. Simultaneously, Europe’s gathering storms amplified their case for a clean break. At last they were on the right side of history as well as of the English Channel. After forty-three years down a wrong turning, the decisive battle was on.

The contest, as it moves in sight of the climax, has become a reprise of the general election: a 24/7 round of policy arguments, statistics-based claims and instant retorts, TV documentaries and panel debates, and set-piece interventions. The three living former prime ministers – John Major, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown – have made eloquent speeches, all for Remain.

In quality and seriousness, the heart of the campaign is a credit to the robustness of Britain’s democracy. It has also turned out to be a festival of acrimony, whose particular dynamic reflects the strategic disparity between the two sides. Remain, reflecting its official designation of “Britain Stronger in Europe,” treats the battle as a general election by projecting the triple themes of the economy, leadership and security with a partisan edge that has flummoxed its adversaries (so used are they to monopolising this quality where Europe is concerned). Its top-down approach proved good enough for the Conservatives in 2015, but will it reach the Labour voters needed to win? Such doubts lay behind the decision to appoint the avuncular Labour MP, former minister and memoirist Alan Johnson to chair a “Labour In for Britain” campaign. So far, however, Johnson’s regional coach tour has evidently been most effective in “stirring up apathy” (to echo an oddly apt criticism once made of Harold Wilson).

Vote Leave spices its political assortment with an insurgent flavour, deploying a gaudy travelling battle bus in search of a local crowd receptive to media-friendly declamations. An impetuous approach is personified by its pyrotechnic campaign director, Dominic Cummings, a former adviser to Michael Gove and possessed of a genius for negative energy. His threat to ITV over which Brexiteer should oppose David Cameron in a televised debate went viral, as did a priceless parliamentary inquisition by the fastidious chair, Andrew Tyrie. (The late journalist Hugo Young, who spoke to Cummings in 2002 when he headed Business for Sterling, reports Cummings’s observation that the crucial factor in a referendum is the status quo – those who want change always have the harder task – though he added that a narrow margin on a low turnout would soon dissolve the mandate. Cummings went on to help stop devolution to England’s northeast, and both his judgements may yet prove relevant to the current campaign.)

Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and Priti Patel increasingly front Vote Leave’s scattershot effort, talking up the government’s failure to limit immigration, for example, and advocating an Australian-style points-based system after Brexit. (“Having lost the economic argument, Vote Leave has gone all UKIP,” writes Philippe Legrainfrom the LSE’s European Institute. In an expert dissection of a “wrong-headed” case, he lambasts Australia’s own policy for its “devilish bureaucratic complexity.”) Indeed, the model has long been advocated by Vote Leave’s rival Nigel Farage, whose equally well-funded “Grassroots Out” lost out in the Electoral Commission’s choice of the referendum’s head-to-head campaigners. The two pro-Brexit groups are not on speaking terms.

Mutual loathing is a feature of the outers, as it is of UKIP’s own interpersonal maze. In fact, the various factions may have incompatible visions of a post-EU Britain. But in the heat of the referendum, such differences are sublimated by the need to concentrate fire on the common EU enemy.

The referendum’s rancorous atmosphere is well conveyed by leavers’ reactions to some of those foreign VIPs, which converge on the accusation that Cameron’s government is orchestrating a “project fear.” (The term was embraced by pro-independence Scots to denounce their opponents, especially the London-based, in the 2014 referendum.) Christine Lagarde’s judgement is an “[interference] in our democratic debate” that reflects George Osborne’s attempt to “bully” the British people, Priti Patel said. This “daily avalanche of institutional propaganda,” both “ludicrous and pitiful,” involves “important institutions being politicised and used to make blood-curdling forecasts,” said Norman (Lord) Lamont, a former Tory chancellor. Obama’s preference could be seen as a “symbol of the part-Kenyan president’s ancestral dislike of the British empire,” wrote Boris Johnson in the Sun. A “lame duck US president about to move off the stage doing an old British friend a favour,” said justice minister Dominic Raab.

There are reams of this, a stew of bad faith topped with conspiracism. The ur-sentence of the entire genre may be Christopher Booker’s in the new edition of his co-written 600-page book The Great Deception (first published in 2005): “The British people have still not really begun to understand how constantly and comprehensively they have been deceived.”

But the silences of the extreme partisans in this debate are equally audible. Seek outers’ rebuttals of Modi or Xi, Bishop or Key – or even Tony Abbott – and you will not find. Daniel Hannan, a prolific and zealous Conservative member of the European parliament who has written paeans both to the Anglosphere (How We Invented Freedom and Why It Matters) and to Brexit (Why Vote Leave), is a notable example of this tongue-tied group.

Hannan did, however, praise a “great speech” made in Australia’s Senate on 21 April, when Victoria’s James Paterson promised that if Britain voted to leave, “friends around the world – including in Australia – would welcome you back into the international community outside the EU.” By contrast, Monash’s Ben Wellings says the “bad news for the ‘outers’ is that the Anglosphere’s supporters are no longer in the ascendancy in Australia,” and that in the event of a Brexit “the dismay among diplomats and businesspeople would be heard from Canberra to Kakadu.”

The swamp of more extreme Euroscepticism, like any world where like-minded fanatics gather, is a disturbed place. That makes serious critiques of Europe all the more welcome, among them Chris Bickerton’s The European Union: A Citizen’s Guide (“The real challenge for citizens in Europe is to give their own national political life a sense of purpose,” with Europe recast “as a new project of internationalism rather than as a tired one of integration or federalism”), Giles Merritt’s Slippery Slope: Europe’s Troubled Future, which puts the EU’s spate of crises in the context of global changes, and the economist Roger Bootle’s revised The Trouble with Europe, whose acknowledgement (unique among Brexiteers) that the process would entail “many painful wrenchings” adds to its considerable authority.

The last point underlines the fact that the decision to be made on 23 June can be about cost-benefit analysis and a balance of judgement, as well as what the Times’s David Charter, in his objective Europe In or Out, calls “a clash of fundamental forces,” namely national sovereignty and cooperative governance.

Where is Labour in all this? It is a question relevant to much more than the Europe debate, as the party continues its retreat to the margins of British political life. A YouGov poll published on 31 May finds that almost 40 per cent of Labour voters don’t know its position on the European Union. Both its leader Jeremy Corbyn and shadow chancellor John McDonnell have spent a lifetime in milieux that regard the union as nothing more than a corporatist (now “neoliberal”) menace. Today they profess conditionally to back British membership insofar as the EU serves Labour interests. A perfunctory schedule includes, most recently, a speech by Corbyn in London on 2 June, formally supportive but substantively critical of the EU (a pro-EU colleague characterised it as “deliberate sabotage”). Labour MPs and local activists fill the advocacy gap as best they can.

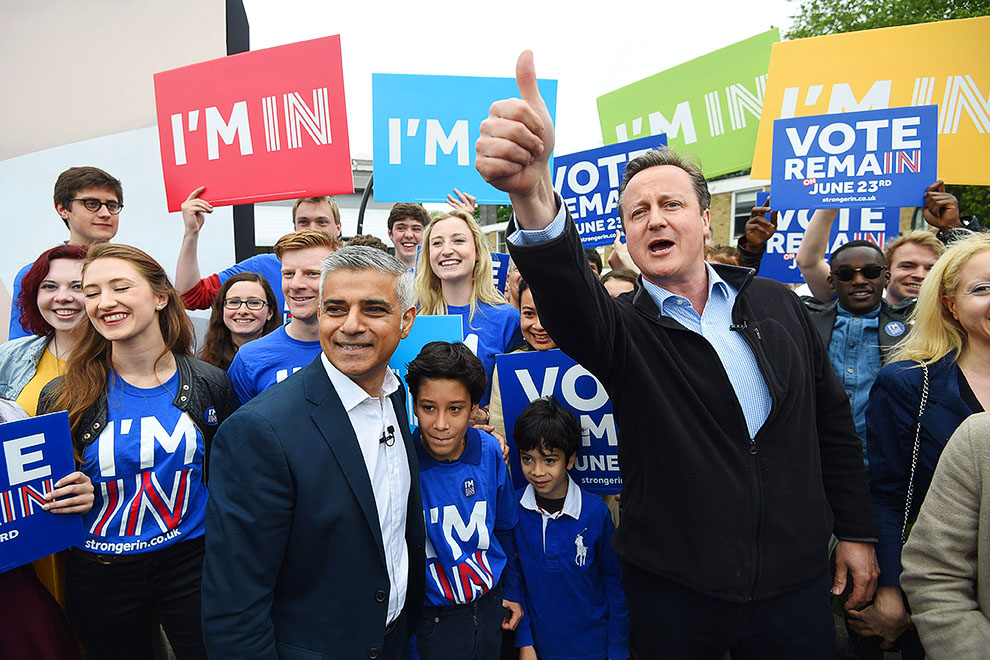

Corbyn refuses to appear alongside any Conservative, a stance backed by deputy leader Tom Watson and McDonnell, who criticised the new London mayor Sadiq Khan for speaking at a rally with David Cameron on 30 May. (It “discredits us” and “demotivates the very people we are trying to mobilise,” McDonnell said.) That Khan himself had been denigrated by Cameron in parliament late in the mayoral race emphasises the contrast in political stature and judgement. Alistair Darling and Ed Balls, former Labour bigwigs, have joined George Osborne on the campaign trail, and Alan Johnson speaks regularly at meetings with pro-EU figures from other parties.

The concern for remainers is that working-class Labourites will be tempted to opt to leave, or will simply not vote. Many of them are already shifting towards UKIP, and are opposed to high immigration and distrustful of the EU. A tailored message would emphasise the employment rights, trading and investment rewards, environmental standards and regional development funds that British membership of the EU has helped deliver. These benefits contributed to Labour’s European “conversion” from the late 1980s, the pivot of a great reversal in British politics in attitudes to the EU. If those rights have become devalorised, Remain as a whole is in trouble.

There is more confidence that Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will deliver majorities for Remain, though their combined 20 per cent of the UK population emphasises England’s importance in the total picture. Moreover, pro-European sentiment in these countries is often exaggerated. That said, if England chooses to quit the EU while Scotland prefers to stay – a much-touted scenario – the argument for a second independence referendum north of the border, presently opposed by a majority of Scots, will acquire real momentum. The referendum’s consequences may yet be as dramatic as the event itself.

“So many factors that bear on these issues are uncertain,” says Roger Bootle, the sophisticated outer. It’s also true that there will be no easy or quick disentanglement between the UK and the EU even if a majority votes to leave. In that event, the government – soon under another prime minister – would invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which outlines procedures for a state to withdraw from the union, something that has never before happened. The process may take two years but could be extended. An unravelling will be difficult, costly and probably fractious. Europe’s larger crises will not make way, nor will Britain’s own (nor too its inevitable share of the former). A precipitous fall in the currency will kick things off nicely.

Britain will continue to need international partners and friends, including the ones that warned against Brexit. The terms of endearment will change, in ways not necessarily to Britain’s advantage – for such is the nature of life as well as politics. At that point, if not before, zealous Brexiteers will variously scream that it’s not fair, suffer buyers’ remorse, lament that “project fear” wasn’t alarming enough, convince themselves they voted the other way and, most of all, seek scapegoats. What they won’t do is take responsibility.

Some observers will draw lessons, and none of them new: about the risks of referendums, of populism, of xenophobia, of conspiracism, and about the illusion of absolute sovereignty. As the British adjust to their new reality, they find that they are more interdependent with the world than ever before. They reflect on the puzzle that they don’t feel significantly different out of Europe, but have the same ambivalences about themselves, their history – and each other – that they always had. “Was it worth it?” debates rage. So does a nostalgia boom. The “Britain in Europe: 1973–2018” exhibition at the British Museum overtakes all records.

No one will have got everything they wanted, after all. Except the author who wrote the definitive book, a huge bestseller, on this period in British history. Its title? The Day the Shouting Had to Stop. •