Canada, France, Ireland, Italy, Japan, South Korea and Spain all do it. Even the United States tries to do it. But the Commonwealth of Australia does not. What is it?

Kudos if you said that those countries cap the amount anyone may donate to a political party or candidate. Double the kudos if you know that the entire eastern seaboard in Australia also has such caps, not just for state parties but for state electoral purposes too.

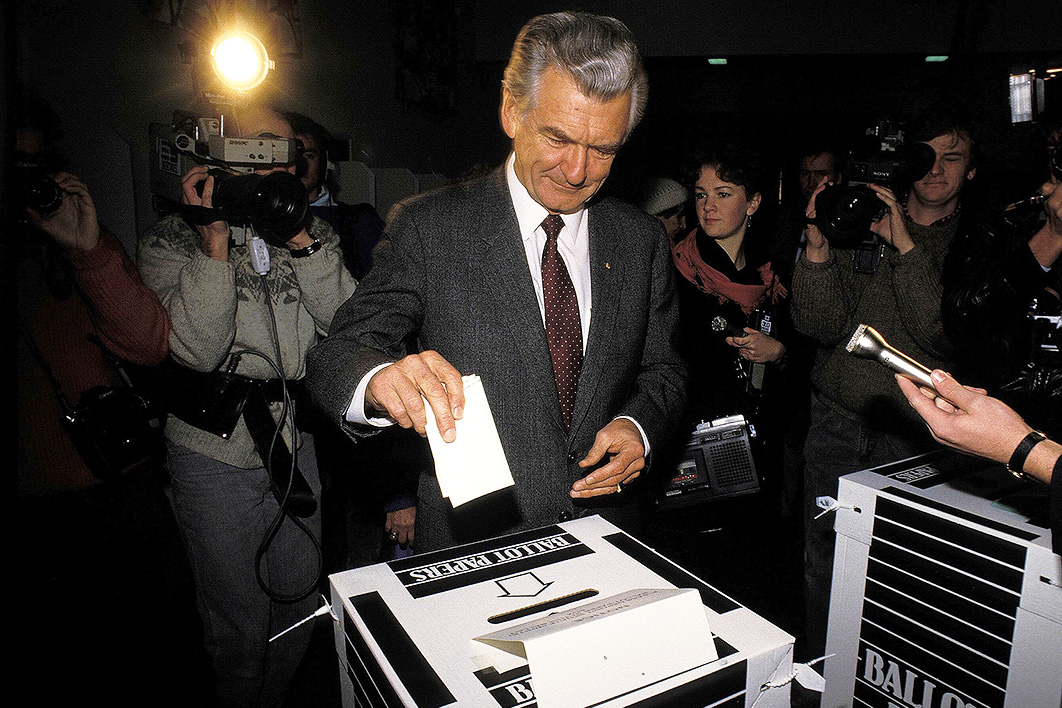

It is forty years since the Hawke government begat the regime that still essentially governs the funding of campaigns for federal elections. That regime still rests on twin pillars: public funding for parties or candidates that attract above 4 per cent of the vote, in return for disclosure requirements whose lack of timeliness is redolent of the paper-and-pen era in which they were hatched.

True, the federal “transparency register” has been widened to include lobby groups that campaign at national elections. But the national electoral laws don’t drill deeply into the financial affairs of parties. Compare Britain, where parties’ audited financial accounts must be published annually — and parties there don’t receive public funding for electoral purposes like their Australian counterparts do.

Whether in an absolute sense, or relative to our usual democratic comparators, the electoral funding and disclosure rules in the Commonwealth Electoral Act remain lax. This state of affairs may align with liberal philosophy in the abstract, but it is not merely passé in terms of developments in the field in the last forty years; it is also corrosive of faith in the integrity and political equality in Australian elections.

With a Labor government ostensibly driven by social democratic norms and an expansive crossbench of Greens and independents committed in principle to more fairness in electoral participation, what are the prospects for renewal? To discuss this, we need to consider the three main dishes on the regulatory menu — disclosure, donation caps, expenditure limits — and then ask if reform is imminent after all these years.

Disclosure is broke: time to fix it

Disclosure at the national level needs to be tighter and more timely. Parties must declare “gifts” — donations earmarked to fund national electioneering — only after the end of each financial year. Their declarations don’t then need to be published by the Australian Electoral Commission, or AEC, until February of the next year. So resources given to parties in the lead-up to the May 2022 federal election need not have been made public until between eight and twenty months after they were received.

In addition, parties need only disclose individual gifts above an indexed threshold that now sits at $15,200 per annum. (Donors are meant to keep tabs on whether a series of gifts exceeds that threshold and, if so, disclose the fact annually.) It gets worse: given our federal structure and history, parties can consist of up to nine registered entities — their national secretariat plus their mainland state and territory divisions. The disclosure threshold applies to each of those entities, not to the party as a whole. So the effective threshold for gifts for national electioneering can be well over $100,000 per party.

You might think, “Well at least this annual ‘disclosure dump’ gives the media a deliberative focus.” It is true that having “real-time” disclosure — say on a weekly basis — and at too low a level could simply snow investigators. The answer to that is to improve the presentation of the data by including tools to easily aggregate and map disclosures across time spans, related parties and entities, and geography.

It is also important to bear in mind the inherent limits of any disclosure system. Disclosure is essentially a kind of freedom-of-information tool that allows the media and rival political players to ask questions. By itself it is no guarantee of integrity, let alone a means to political equality. It can even heighten cynicism or normalise unlovable donation practices. Companies may think they need to keep up with the largesse of competitors seeking to ingratiate influence; party treasurers can hit up donors to a rival party and say, “What about us?”

Regardless of such considerations, the national disclosure system is clearly broken: that much has been known for years. But the major parties have also increasingly driven a truck through the system, and the AEC hasn’t stood in their way.

How? The major parties operate business-oriented fundraising arms under names like the Liberal Party’s Australian Business Network and the Federal Labor Business Forum. These outfits charge huge subscription fees: not to be a member of the party proper, but to belong to a kind of exclusive networking club. To magnify the exclusivity, fees have been tiered across “platinum,” “gold” and “silver.” The fee for the highest tier has reportedly inflated from $110,000 to $150,000 in recent years.

When these fundraising arms organise notionally come-one, come-all dinners (like Labor’s $5000-a-head budget dinner hosted by PwC or a $5000-a-head “boardroom lunch” with treasurer Jim Chalmers), the ticket cost is set below the disclosure threshold. This is an old practice; the scandal today is that these large, tiered subscription fees are not being disclosed.

Under electoral law, a political donation is something given for “inadequate consideration.” But the parties happily encourage subscribers to claim they are receiving more than adequate consideration. Quelle surprise! As Woodside Energy’s CEO explained some years back, this leaves it up to people like him to decide whether to make “voluntary” disclosures.

Despite being armed with significant forensic powers, the AEC has taken such assertions at face value. It told the ABC recently that it leaves it up to the subjective — and conflicted — view of those paying for access to the parties. Donations up to ten times the disclosure threshold can therefore be hidden in plain sight.

All this ignores the objective nature of value in most real-world dealings. Parties are hardly in the events industry. The AEC could demand to be informed of the events held by each forum/network and then commission experts to assign an upper market value to the event-as-an-event (including an allowance for the attendance time of ministers or MPs). The AEC could also inspect the accounts of these fundraising arms to see what surplus they generate, per average subscriber, for the party coffers.

In short, the major parties are nakedly soliciting revenue, with a nod-and-wink as to anonymity, in return for selling premium access — and the regulator is standing by. Selling access corrupts basic public law values: politics as a public trust and the franchise as an emblem of the equal worth of all people. Why on earth would an ordinary person voluntarily join one of the major parties today when they are seen as largely superfluous to the electoral machine? As if rubbing salt in the wound, last year the major parties convinced the courts that any membership rights contained in their own rules are legally unenforceable.

Capping donations

Presently, the only “real” limit on national political donations is a ban on “foreign” donors, a recent development driven by concerns about Chinese money. I put “real” in quotes, since nothing is more fluid than international finances. That means the law is not really enforceable offshore, and so assumes that receipts are careful screened by Australian political actors. While the parties have been willing to twist and stretch disclosure law, the opprobrium for breaching a “foreign” donor ban is probably sufficient for the parties to self-police the source of gifts.

That leaves non-foreign, ridgy-didge Aussie donors: a residual category that ranges from citizens (wherever located) and permanent residents through to businesses incorporated here or simply possessing a principal place of activity here. Unlike in the sample of countries listed at the start of this piece, they face no donation limits. Is this a problem?

It may be, for political integrity and equality. If disclosure requirements were more meaningful, and if the new National Anti-Corruption Commission performs to its potential, we might be right to leave political integrity to those regimes.

What then of political equality? Political donations are partly acts of political association. This means they cannot, constitutionally, be banned outright. But they can be limited — in their size and in who makes them. Generally, we should welcome donations from a wide range of sources to help keep parties connected to a broad social base. Indeed, donations to parties and candidates of up to $1500 per annum are tax-deductible for individuals. On the other hand, big donations, even those made on the basis of mateship or ideology, undermine political equality.

Given this pervasive effect on political equality, why are donation caps not more prevalent in Australia? One clue lies in two countries absent from the list of those with caps: Britain and New Zealand. Like Australia, they have a longstanding Labor Party (albeit they spell it properly, as “Labour”).

“Surely these parties of the ordinary worker would support caps?” you say. Well yes, in principle. But when caps are introduced, the law is confronted by the problem of how to deal with the affiliation fees paid by the trade unions that formed those parties and still prop them up in the lean times of opposition. (Modern Labo(u)r parties do okay from corporate donations when they are in power or on the verge of power, but less well when facing the wilderness, thanks to their pragmatism and that of business donors.)

A second hurdle for caps is whether new political forces may need an injection from a sugar daddy in order to challenge the might of the existing major parties. This is less relevant for an eponymous self-funded party like the former Palmer United Party (now the United Australia Party) but very important for a more genuine movement like the teal independents who were turbocharged last year by Climate 200 support.

The key figure behind Climate 200, a progressive entrepreneur who inherited part of the vast mining and corporate raiding fortune of Australia’s first billionaire, has even written a book celebrating the movement. It may be no coincidence that teal candidates did much better in the 2022 federal election — without caps on donations or expenditure limits — than in this year’s NSW election, where both are capped.

Limiting spending

The third option on the menu is expenditure limits, which constrain how much parties, candidates and lobby groups can spend on certain electioneering costs. These limits are now common for state elections in most of Australia, as this table shows. (Victoria and Western Australia are the odd ones out, Tasmania only has them for its upper house elections, and in South Australia they are nominally “opt-in” as a condition of public funding.)

Limits on expenditure drive the British and New Zealand systems, and are a feature across Europe and the Americas. (They cannot be mandated in the United States, and opt-in spending limits there have fallen by the wayside.)

In principle, expenditure limits do several jobs. They squarely address the “arms race” problem, which Mr Palmer has reignited in Australia. In constraining the parties’ demand for money, these limits free up them and their leaders to focus on genuine public business and may reduce demand for dodgy donations. They may also help deliberation by making campaigns less cacophonous, something that is a turn-off for many electors.

Expenditure limits should also be easier to police than donation limits. While donations are inherently behind-the-scenes, campaigning needs to be public to be effective. That remains the case even with the advent of highly targeted online campaigns, although that development requires transparency from social media companies.

When it comes to expenditure limits, the devil lies in the legislative detail. With no fixed terms for federal parliament, the capped period is not easy to define. (At Westminster, it is up to a year ahead of an election.) Exactly what is covered by “electoral expenditure” also needs careful design and definition. And the coordination of campaigns — between trade unions or corporate groups, for example — needs to be controlled to keep caps from being rorted.

Most vexed of all is the question of what limits should be put on lobby group electioneering — not least with some members of the High Court suggesting, in 2019, that the idea of a level electoral playing field limits differential treatment of parties/candidates and lobby groups. If so, this is an odd heresy. Representative elections are necessarily focused on parties and candidates; parties have ongoing reputations to protect, and party leaders and MPs are publicly accountable in myriad ways that lobby groups are not.

Reforming the morass

Fifteen years have passed since the states began modernising the law of money in electoral politics. Yet substantive change has been absent nationally. If inertia had its way, this dual track of state innovation and national enervation would be unlikely to change.

As we have seen, the national transparency net has widened to rope in electioneering lobby groups but has simultaneously frayed. Observers are optimistic, however, that federal disclosure rules will be tightened to include a lower disclosure threshold and more frequent disclosure obligations. None of this is rocket science. Models exist aplenty, from New York City to Queensland, for something approaching continuous disclosure in the internet era. On the question of which income will need to be disclosed, we must pray that the Greens and crossbenchers lean on Labor to deal with the “business forum” loophole it helped manufacture.

Tasmania is on the verge of becoming the latest (and last) subnational jurisdiction to update its law in the area, and its bill is instructive about what not to do. Across 265 pages it weaves an intricate web of registration and accounting requirements. Yet it does little more than bring in a regular disclosure regime, sweetened with generous public funding for elections and for party administration. The Liberal government wants to set the disclosure threshold at $5000 per annum: pretty high for a small state.

After self-inseminating his party with over $200 million over the past two national elections (mostly via Mineralogy Pty Ltd), Mr Palmer’s recent forays into electoral politics may leave one main legacy: some form of donation cap. To have any effect, it will need to include a suturing of that business forum/network loophole.

Any federal cap is likely, I suspect, to be set at a high level. The major party treasurers — along with otherwise “progressive” electioneering groups like Get Up! and Climate 200 — will baulk at setting donation caps anywhere near as low as some states have. (Victoria is the most parsimonious — just $4320 currently over the four-year term.)

This leaves expenditure limits as the main new item on the menu. Again, the shadow of Mr Palmer looms large; but not just his. Finding himself outspent by a teal rival in a previously blue-riband Sydney seat in 2022, a Liberal MHR complained that his opponent’s spending had been “immoral.” Is it too cheap to note that his party could have swallowed its economically libertarian instincts at any time during its three terms in government and legislated limits? Better late than never! Temperance bandwagons were mostly full of recovering addicts; and, as St Augustine ironically put it, “Lord, make me chaste and celibate, just not yet.”

Federal parliament’s Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, a multi-party committee with fourteen members, has held public hearings, including on electoral finance reform, over a seven-month period. (MPs, even more than public lawyers, seem fascinated by electoral law.) Its report is due soon enough. The mix of compromise, competing principles and self-interest manifest in its recommendations will make for compelling reading. •

This article first appeared under the title “Money in Australian Electoral Politics: Reforming the Morass” in AusPubLaw.