The weekend’s extraordinary election result in Taiwan underlines how quickly the times are changing in East Asia, and the need for Australians to rethink outdated shibboleths. During their formative student years, many of Australia’s current leaders saw much to be admired in the rise of China, whereas they often saw Hong Kong as a decaying colonial outpost and Taiwan as a bastion of US-led imperialism. Today, any observer with experience of the region has been forced to turn that view utterly on its head.

It’s important to start with the central issue. Xi Jinping, China’s sole dominant figure, has inexorably personalised and centralised political and economic power. His core quality — complemented by his propensity to take political risks and a significant measure of good luck — is his zeal.

Xi’s driving belief is that the Communist Party must remain in perpetual and untrammelled control. More than an end in itself, party rule comprises a belief system, which is evident in the quasi-religious language used by party figures. (In one recent case, Australian Liberal MPs Andrew Hastie and James Paterson were requested to “sincerely repent” of their criticisms of China.)

China is being transformed into one of the most ubiquitously surveilled and controlled societies the world has seen. Beijing is making extraordinary efforts to rewire the loyalties and identities of China’s ethnic minorities, including the Uighurs and Tibetans, and its religious adherents, including Buddhists, Muslims and Christians, so that their primary culture becomes essentially Han Chinese.

That the ultimate success of this great, ambitious project that comprises the People’s Republic of China — created of course by Mao Zedong, Xi’s foremost hero — may not be inevitable, is slowly being sensed beyond the party core, seventy years after it began.

To date, the country’s economic growth has driven a rapid rise in global influence and has been crucial to the success of Xi’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. But growth is inevitably flattening, and demographic and structural constraints may mean that China’s economy won’t surpass that of the United States for many decades.

In recent weeks, Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia have expressed unusually strong concern, bordering on anger, about Chinese fishing and naval incursions (the two being often hard to disentangle). Along with South Korea, Mongolia, Singapore and just about every east Asian nation, these countries know much about “foreign humiliation,” but unlike China they have declined to treat it as the key driver of their foreign policies.

Meanwhile, the world has watched, sometimes with intense anxiety, the depth of commitment to freedom, democracy and the rule of law on display in Hong King. Admiration has been tempered, though, by fears of a cataclysmic response from Beijing.

Those values clearly run far deeper among Hong Kongers, and across a far larger proportion of the population, than most observers had previously imagined. They are certainly more intense than the commitment to money making that many, including Beijing, had assumed to be the core value of the territory. The local elections there six weeks ago underlined this in spades, with pro-democracy candidates winning 388 seats to the pro-Beijing candidates’ sixty-two.

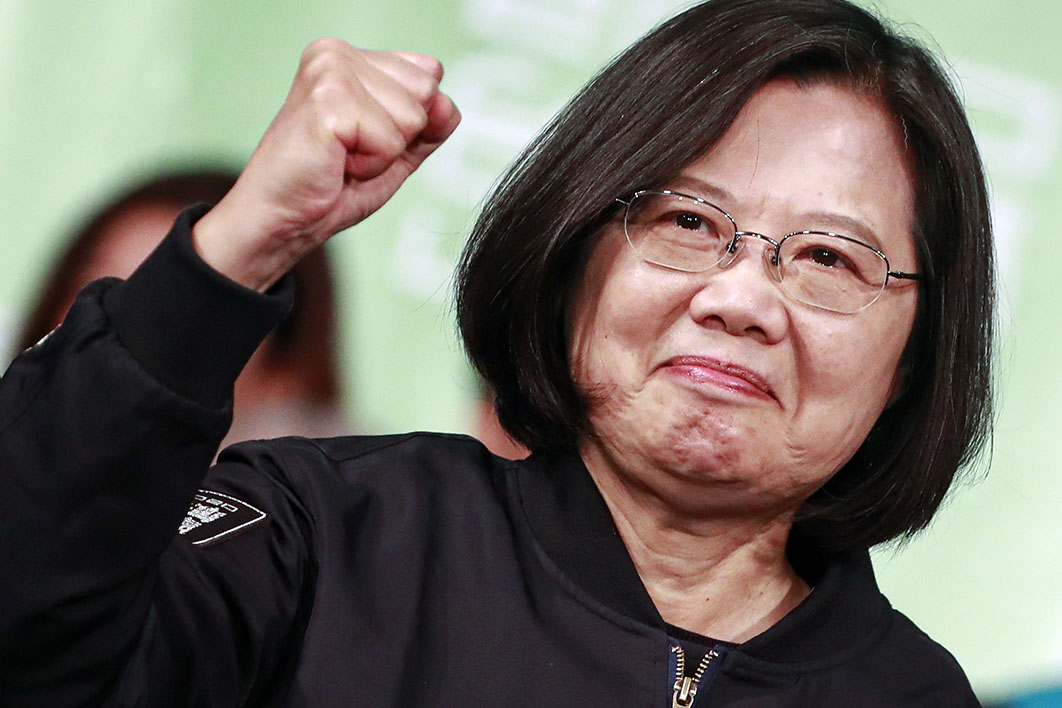

Now Taiwan has also spoken, giving president Tsai Ing-wen an overwhelmingly victory in her bid for a second term. Her own vote rose to 57.1 per cent, a margin of almost 20 per cent over her Kuomintang opponent, and her Democratic Progressive Party retained control of the Legislative Yuan, or parliament, albeit with the loss of half a dozen seats.

With just over twenty-three million people, Taiwan has about the same population as Australia. Its physical beauty and environmental variety are extraordinary. Its Aboriginal tribes bear strong linguistic, cultural and hereditary affinities with the people of the Pacific islands, many of whose ultimate origin, their stepping-off point from Asia, was Taiwan. In contrast with China, the country’s wealth is distributed more evenly than in most Asian countries. Culturally, it is highly creative. It is Australia’s sixth-largest export market.

In just thirty years Taiwan has thrown off the authoritarian system created by the Kuomintang military after it decamped from China in 1949. Now a model liberal democracy, its government has changed hands three times — between the centre-right “blue” Kuomintang and the centre-left “green” Democratic Progressive Party — remarkably smoothly.

Tsai has apologised for the historic oppression of Aboriginal tribes, presided over the introduction of same-sex marriage, and overseen an increase in the economic growth rate to 2.6 per cent while maintaining low unemployment. Last year, $A30 billion was reinvested, chiefly in local high-tech operations, by Taiwanese companies that had long focused on developing their businesses on the Chinese mainland.

Unlike recent elections, the weekend vote focused on identity rather than living standards. Young Taiwanese in particular, but also a majority of the population as a whole, identify as Taiwanese rather than Chinese, and only about 13 per cent are descended from those who came from mainland China in the 1940s. The continuing turmoil in Hong Kong has been much on their minds.

Taiwan has long had a unique identity. Dutch and Spanish naval expeditions fought for control of its key ports in the early sixteenth century, with immigration from mainland China following. The Europeans favoured the farming and labouring skills of the new arrivals, and relations with the indigenous inhabitants were tense.

The island wasn’t exactly treasured by the Manchus, whose Qing dynasty controlled China at the time, with Emperor Kangxi describing it as “a ball of mud beyond the pale of civilisation.” In 1895, following a naval defeat, the Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan, which introduced modern technologies and infrastructure during its fifty-year rule.

Taiwan is one of the “tigers” that drove Asia’s economic resurgence. Like Hong Kong, it invested heavily in China after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms opened up the country, and it backed its capital with management skills and technical training. But the opportunity to prosper did not fully occupy hearts and minds in Taiwan or Hong Kong, as recent events in both locations have amply attested.

With Xi Jinping restructuring his party and striving to incorporate all of China’s troubled borderlands, these outlying populations have tended to reassert their identities. China’s one country, two systems formula, also proposed for Taiwan, has very little attraction, especially for young people. They feel little or no connection to a state they see as increasingly reverting to a modernised form of restrictive Maoism.

As usual, Beijing blames this kind of unrest on Western “black hands,” But it is becoming clear that today’s young Taiwanese and Hong Kongers, who increasingly exchange analyses and information, are even more deeply committed to liberal democracy than most of their Western counterparts.

As President Tsai said on New Year’s Day, “Democracy and authoritarianism cannot coexist within the same country. Hong Kong’s people have shown us that ‘one country, two systems’ is absolutely not viable.” Taiwan’s voters, and especially its youth, have resoundingly agreed with their rather academic but increasingly politically canny president.

But Xi is not for turning, or even for talking. Despite needing to come to terms with the popularity of Tsai and her party, and despite the fact that Tsai is the rational, even bureaucratic, kind of leader with whom such a conversation could be feasible, Xi has not sought to negotiate with her.

Throughout his career, in fact, the Chinese president has shown a propensity to double the odds rather than sticking with the cards in his hand, and to instruct rather than engage in conversation. He clearly believes that bringing Taiwan into the Chinese embrace would cement his place in history — something that his public remarks indicate is of great moment to him.

The resulting contest of ideas and wills is one for the ages. It is also a battle in which Australia, gradually becoming aware of the need to assert its own political culture, will become increasingly invested. •