It is tempting for Peter Dutton and his Liberal colleagues to put the loss of Aston down to Victoria’s left-liberal culture. The last federal election they won there was in 1996. They’ve won only one state election in Victoria this century.

As the party’s former assistant state secretary, Tony Barry, put it ruefully on Saturday night: “The Victorian Liberal Party is where hope goes to die.” Decades of infighting and election failure have hollowed out its membership, leaving it open to branch stackers and reactionary nutters. The Coalition as a whole has less than a third of the seats in the Legislative Assembly and barely a quarter of Victorian seats in the House of Reps.

Unquestionably, Victoria has become a stronghold of the left. But these days, so is Western Australia, and so is South Australia. Federally, so is Tasmania. Labor is back in power in New South Wales — and don’t mention the ACT.

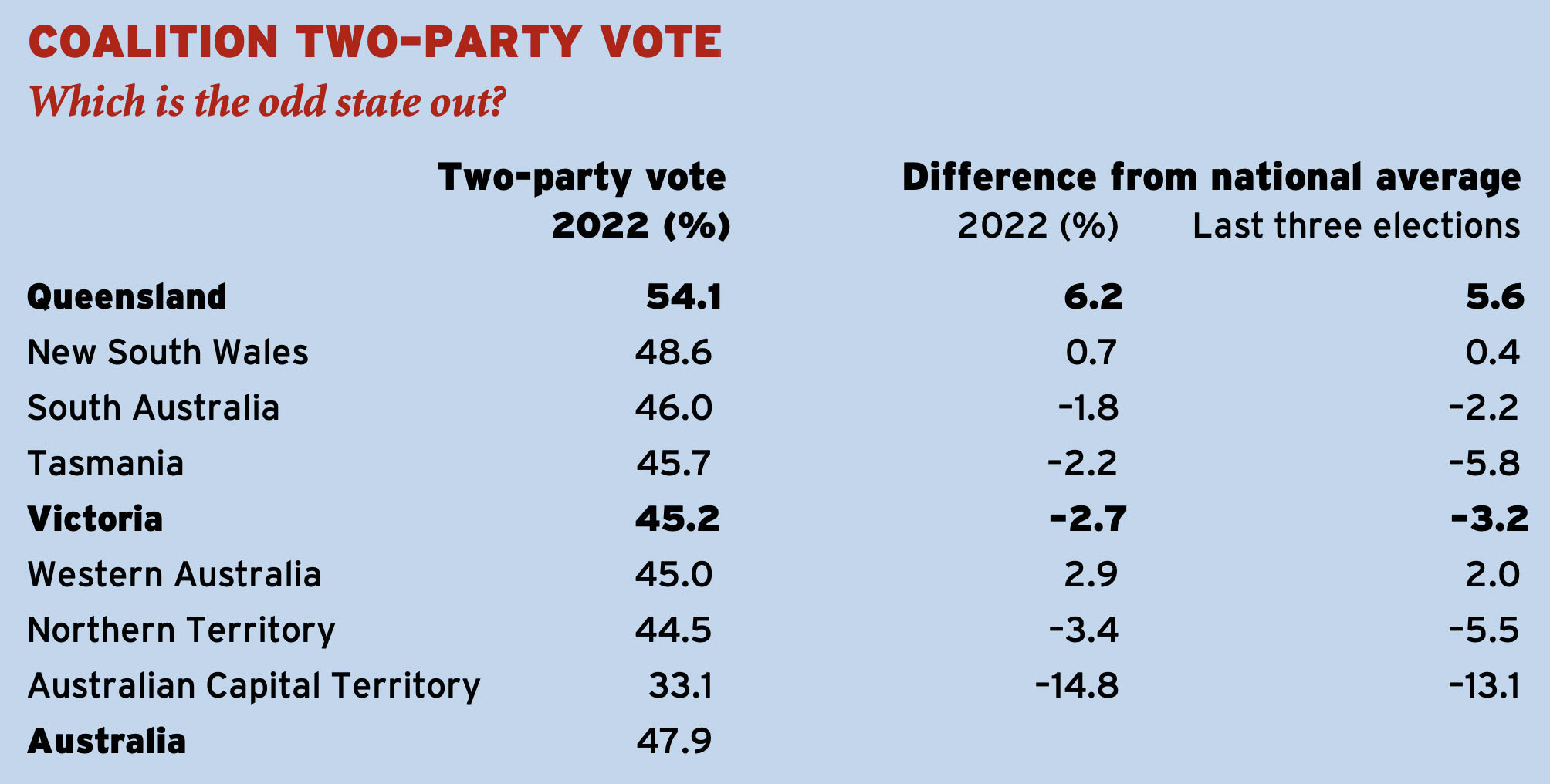

In fact, if you look at voting over recent federal elections, Victoria, along with New South Wales and South Australia, is among the three states closest to the centre of the Australian political spectrum. The odd state out isn’t Victoria. It is Peter Dutton’s home state of Queensland.

Australian Electoral Commission figures

At last year’s federal election, the Coalition won 70 per cent of Queensland’s lower house seats but just 30 per cent of seats across the rest of Australia. Peter Dutton doesn’t need to go to Melbourne to be in alien territory; he’s in it as soon as he leaves his home state.

The Coalition is now down to ten federal seats in Victoria, but it also has just five in Western Australia, three in South Australia, two in Tasmania and none in the ACT or the Northern Territory. Even in New South Wales it is down to sixteen seats, or one in three.

The Coalition’s problem is not Victoria, it is Australia — or at least Australia minus Queensland. To write off a loss like this as due to being in hostile territory would be a huge, self-indulgent blunder that could only damage the Coalition. As the election results showed clearly, it has lost support in every other mainland state.

Yes, it would help if it could fix up the problems of the Victorian Liberal Party. But that can happen only if the federal and state Liberals use their time in opposition to rethink their policies — constructively, to ensure they are “sound and progressive,” as Sir Robert Menzies urged long ago.

This is renovation time. Both the Coalition parties need to remodel themselves into the kind of party that sound and progressive Victorians would want to be part of: the Victorian Nationals have shown the way. And that would similarly reinvigorate both parties in the rest of Australia. The Queensland LNP can’t be allowed to have a veto on federal Liberal and National policies.

Maybe only a Queenslander can explain one puzzling aspect of that state’s electoral behaviour. In Victoria and most other states, people tend to vote the same way at federal and state elections. But a lot of Queenslanders clearly vote different ways.

The Coalition has won a majority of Queensland’s lower house seats at nine of the last ten federal elections. At state level, though, it has won only two of the last ten. In the past thirty years, Labor has spent more time governing Queensland than it has governing Victoria.

Labor has won all three of Queensland’s most recent state elections, averaging 51.8 per cent of the two-party-preferred vote. Yet it has won only a handful of seats at federal elections, and just 44.5 per cent of the votes.

And that’s not new: it’s been a recurring theme in Queensland’s history, including during Labor’s long twenty-five-year reign from 1934 to 1957. Some Queenslander, please explain. •