The voters have spoken. They didn’t say what most of us expected them to. The return of the Morrison government is the most unexpected election result Australia has seen since John Hewson lost the “unlosable election” of 1993. It will take a while for us to fully understand what happened.

It may be that Labor lost the election for the same reason that Hewson lost in 1993. They proposed an ambitious plan of tax reforms. Their opponents launched an all-out scare campaign that misrepresented the taxes, created fear, uncertainty and suspicion, and won the election. If that’s the explanation for Labor’s shock defeat, it is a bad sign for the chances of future reform — and hence, for the quality and wellbeing of Australian society.

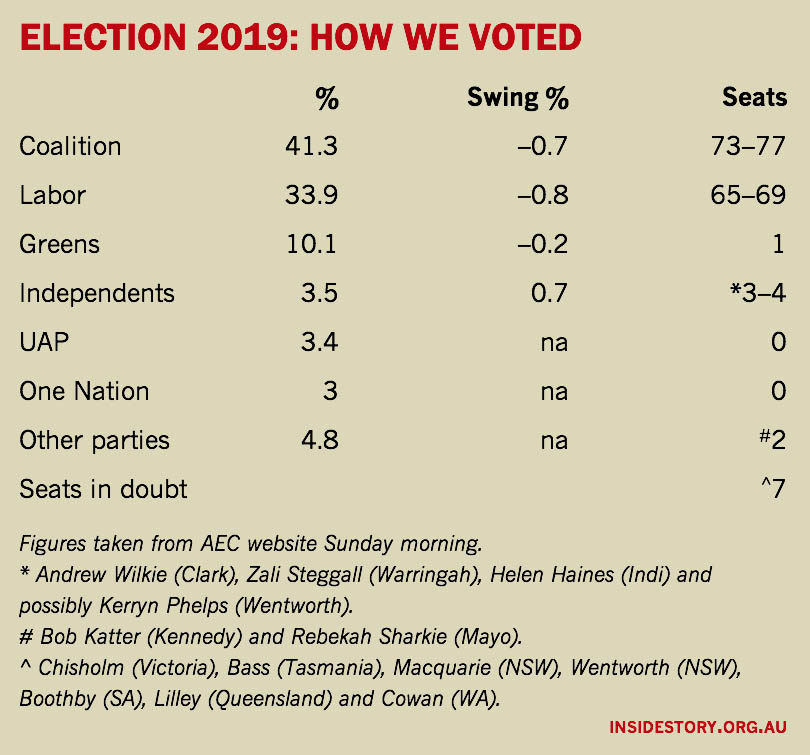

At most, seven seats remain in doubt. More in doubt is whether Scott Morrison will lead a majority government or a minority one. As of Sunday morning, the Coalition was ahead in seventy-six of the 151 seats. Labor was ahead in sixty-nine, and others in six. That’s very tight, especially when in Bass, the Coalition led by just over 300 votes.

It could easily end up in a minority on the floor of the House, as it was before the election. Indeed, the current state of the parties in the count is exactly the same as it was six months ago, before Julia Banks defected from the Coalition. But if that’s how it ends up, that should be workable — and if not, it will probably be because the government is trying to do something fundamentally wrong.

There will be plenty of time for considered opinions on why Labor lost its own unlosable election, after having led in every opinion poll since September 2016. It might help us understand why it happened if we first learn more about exactly what happened.

1. We expected a medium-sized swing to Labor. Instead we got a medium-sized swing to the Coalition

The opinion polls estimated on average that Labor would win 51.7 per cent of the two-party vote, a swing of just over 2 per cent. Instead, the ABC’s Antony Green estimated at the end of Saturday night that the final results would show a swing to the Coalition of 1.5 per cent, giving Labor just over 48 per cent of votes after preferences. (The Australian Electoral Commission’s results website shows a two-party swing of 0.5 per cent, but that excludes sixteen seats where the final contest includes a Green, independent or minor party.)

That is a big difference from what the polls were forecasting, and well outside their margin of error. It follows the Victorian election six months ago when the polls got it even more wrong, that time by underestimating Labor’s vote. For a decade, we’ve had the good fortune of having opinion polls we can trust. Now, alas, we can no longer rely on them for accurate information on how the voters see things.

(When did the polls wander off track? Before all those bad Newspolls helped to overthrow Malcolm Turnbull? Yesterday’s Newspoll was 3.5 per cent out. Had the public long been saying one thing to the pollsters, while thinking something else? Or was the result just the effect of the scare campaigns against Labor’s tax reforms and against Bill Shorten?)

The outcome also made fools of the punters — and of Sportsbet, which on Thursday, as a publicity stunt, offered to pay out early for anyone who put their money on Labor. Even Ladbrokes was offering odds of 6 to 1 against the Coalition until the voting stopped and we discovered it had won.

The only polls that gave any hint of the result were the final seat polls YouGov Galaxy published in the final days, and even they were hit-and-miss. (They reported the Queensland seats of Herbert and Forde as 50–50, but the Coalition won them both by at least 58–42.) But the polls did find that in some seats the swing was to the Coalition, and in others the swing to Labor fell short of what was needed. But because seat polling has a poor record, most of us discounted them as reliable evidence.

2. We were divided. Any district within ten kilometres of a GPO was probably swinging to Labor. Any district outside that was probably going the other way

In most seats, the swing was to the Coalition. But there were exceptions. In Victoria, Labor won two-party swings of 2 per cent or more in roughly half the seats. And in the inner cities, of whichever city in Australia you look at, the Coalition lost ground, and Labor and the Greens gained.

The election has left Australia more divided than ever. In central and north Queensland, electorates suffering high unemployment were looking forward to the prospective Adani coalmine, so they dumped Labor and swung massively to the Coalition.

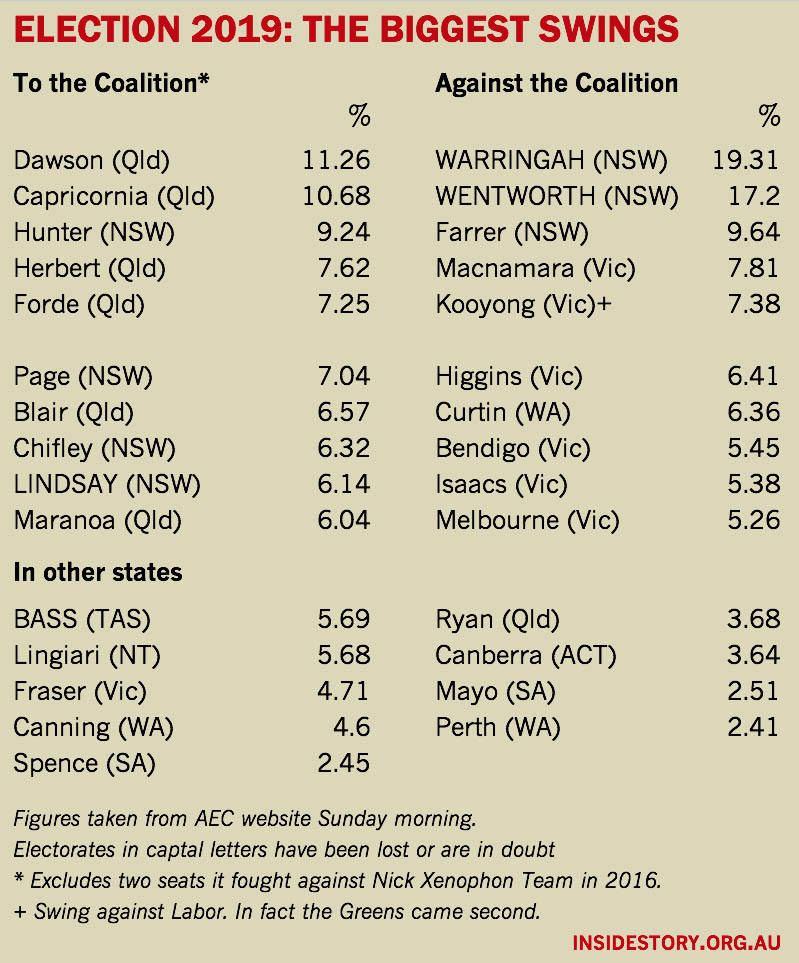

It sums up the mood in central and north Queensland that the biggest swing to the Coalition anywhere went to the MP whom southerners see as a joke: George Christensen. He won an 11.26 per cent swing in the Mackay-based seat of Dawson, and there were big swings on either side of it: 10.68 per cent in Capricornia (Rockhampton) and 7.62 per cent in Herbert (Townsville).

The anti-Labor mood in Queensland was felt everywhere outside the southeast except Leichhardt (Cairns). It extended to outer-Brisbane seats like Blair, Forde and Longman (which the Coalition won back), and even to Bonner in the eastern suburbs and to Lilley in the north. Wayne Swan’s old seat was shaken by a 4.8 per cent swing, although it looks like Labor will survive.

But inner-suburban Brisbane, Liberal or Labor, went the other way. Ryan, Brisbane’s poshest seat, recorded a 3.68 per cent swing to Labor, and there were noticeable swings in its neighbours, Brisbane and Griffith. In all three, the Greens’ vote topped 20 per cent — at least partly due to their fervent opposition to the Adani mine.

Adani has become a fault line dividing Australians. To people in regional Australia, especially regional Queensland, the mine represents an opportunity for well-paid, full-time private-sector jobs: manna from heaven, to relieve the lack of jobs. But to others, especially in inner cities, it represents expansion of the world’s use of coal, the fuel largely responsible for warming the planet, with all the risks that follow as icebergs melt, weather patterns worsen, the sea rises, and low-lying land is submerged.

The first group doesn’t want to see the government tackle climate change seriously; the second insists that it must. Scott Morrison is basically with the first group. But unless the Coalition accepts that climate change is real and serious action has to be taken urgently, the reality of the climate emergency means the issue will keep growing like a cancer within the party.

But this cancer is spreading within Labor ranks too. Outside central and north Queensland, the biggest swing against Labor was in the coalmining areas of the Hunter Valley. Frontbencher Joel Fitzgibbon lost 9.24 per cent of the vote and held on only narrowly in his normally safe seat of Hunter, while neighbouring seats like Shortland and Paterson also recorded big swings against Labor. Neither party has an easy way out of its dilemma.

The division within Brisbane was repeated in other cities. In Sydney, a swing of almost 20 per cent saw independent Zali Steggall eject former prime minister Tony Abbott from his seat of Warringah, while across the Heads, fellow independent Kerryn Phelps is still a chance to retain the Wentworth seat she won in last year’s by-election. Bradfield, Bennelong, Mackellar, North Sydney: the affluent Liberal heartland swung as one against its government. It’s hard to believe it did so because it was attracted to Labor’s tax reforms. Climate change was surely the key issue.

But on the other side of Sydney, in Labor’s heartland, it was a different story. The Liberals won back Lindsay with a swing of 6.14 per cent, and won an even bigger swing in Chifley against Labor trailblazer Ed Husic, the parliament’s first MP from a Muslim family. Shadow treasurer Chris Bowen’s seat of McMahon was shaken by a swing of more than 5 per cent.

In Melbourne, the trends we saw in November’s state election continued with slightly lesser force. The swing to Labor in the Liberals’ blue-ribbon seats was 7.38 per cent in Kooyong, 6.41 per cent in Higgins, and just under 5 per cent in Goldstein. That was not enough for any of them to fall to Labor or the Greens, but Higgins is now more marginal than La Trobe, which is a classic outer-suburban marginal that the punters expected to fall to Labor this time but instead went strongly the other way.

In Perth, Labor failed to take any of the three marginal middle- and outer-suburban seats it had hoped to gain, but won a 6.36 per cent swing in the city’s richest electorate, Curtin, vacated by former foreign minister Julie Bishop. In the ACT, it won a 3.64 per cent swing in affluent, educated Canberra, now an inner-suburban seat straddling both sides of the lake.

3. The Greens polled well, One Nation so-so, Clive Palmer no-no

The seat of Canberra embodies another trend: by and large, these big swings to Labor in two-party votes in the inner cities were matched by a big rise in the Greens vote. In Canberra, Greens candidate Tim Hollo, who was chief of staff to former Greens leader Christine Milne, ran second for most of the night, and was overtaken by the Liberals only when the pre-poll votes came in.

Across Australia, the Greens vote was almost unchanged at 10.1 per cent, but that masks an increasing geographical division. It continues to build as a formidable force in the inner suburbs, Liberal and Labor, while losing relevance almost everywhere else.

The $50 million Clive Palmer reportedly spent on election advertising certainly damaged Labor, but did nothing for Clive’s electoral chances. His United Australia Party ran in almost every seat, but won only 3.4 per cent of the vote, a third that of the Greens. It got to double figures only once: in Riverina, where it was the only right-wing alternative to Nationals leader Michael McCormack, and hence reaped the gains of the widespread anger shown in the area at the state election.

Bad results for the Liberals often went hand in hand with a strong showing by the Greens, and the same was true for One Nation’s impact on Labor. Pauline Hanson’s party was unable to top 20 per cent in any seat in Queensland, but it did so in the seat of Hunter, almost pushing the Nationals out of second place. Bob Katter held his seat of Kennedy for Katter’s Australia Party, but his bid to expand its reach to neighbouring seats failed.

4. The independents’ surge was patchy, but still reverberated

The independents did better than expected in some areas, worse in others. Former Olympic skier Zali Steggall had an emphatic win in Warringah to send Tony Abbott on his way. Health administrator and academic Helen Haines won an unexpected victory in Indi to succeed Cathy McGowan. And Kerryn Phelps, written off by the punters weeks ago, is still in the contest to hold Wentworth, although the Liberals’ Dave Sharma now has a 1000-vote lead.

But Rob Oakeshott failed to make the soufflé rise twice in his attempt to win Cowper, and Albury mayor Kevin Mack was easily beaten by former health minister Sussan Ley. Apart from Andrew Wilkie, now a fixture in his Hobart electorate, no other independent topped 15 per cent of the vote.

But one long shot has been overlooked. In Mallee, where Nationals MP Andrew Broad retired early as a result of an unfortunate trip to Hong Kong, thirteen candidates have sliced up so much of the vote that his intended successor, Anne Webster, won only 29.5 per cent. That leaves a lot of preferences to be distributed, especially between three independent candidates. Webster is likely to win, but no one knows for sure where those preferences will end up.

5. More than one in twenty Australians voted informal

With the votes of 75 per cent of electors counted, some 677,000 Australians have voted informal. They include well over 10 per cent in Mallee and six other seats, all in western Sydney. In some seats, more than one in eight votes were informal. Some of that was presumably deliberate, but some is due to inconsistent voting rules at federal and state level, which are hard to explain to inattentive voters, or those with little English.

Most of them are in Labor electorates, so it should be Labor’s responsibility to find ways to usher in common laws at federal and state level. Should voting be compulsory? Should preferences be compulsory? We should debate how to avoid the unnecessary disenfranchisement of so many.

Arguably, it could have affected the result in a seat like Lindsay, where more than one in ten voters had their votes ruled informal.

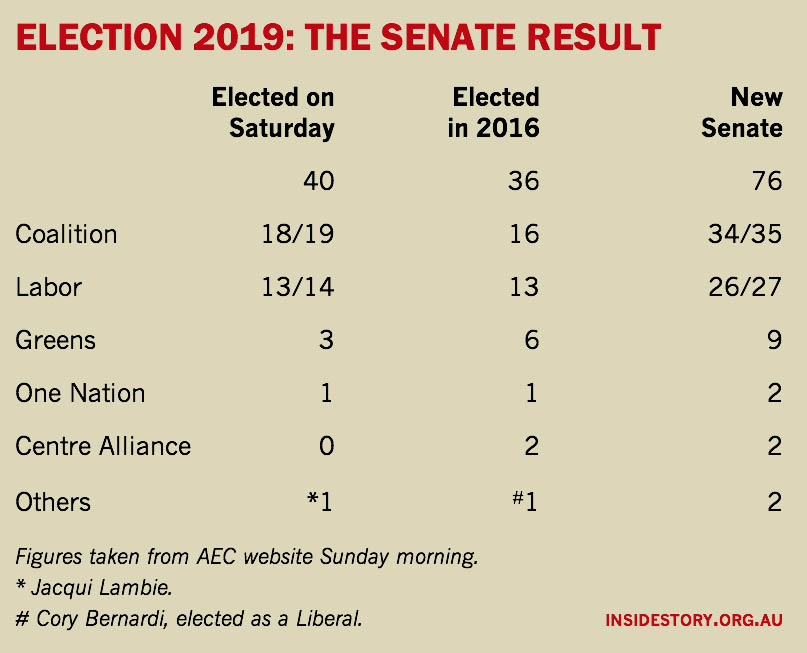

6. Coalition Senate gains could make it easier to pass key bills

The Senate count is only half-done, but the results are clear in almost all seats. The one exception is in Queensland, where the collapse of Labor’s vote could see it lose a Senate seat to the Coalition. Elsewhere the Senate results are much as I forecast, but with the Queensland outcome updated by Lonergan’s final poll for the Australia Institute — one of the few polls in the whole campaign that proved to be of any use — which predicted the failure of Clive Palmer.

On the right, the Coalition has won three of the six seats in all states except Tasmania and probably Queensland. Jacqui Lambie will return to the Senate from Tasmania, and One Nation’s Malcolm Roberts from Queensland.

Palmer and his United Australia Party did not come remotely close to winning a seat in the Senate or the House. One Nation proved it is still by far the biggest of the many non-Coalition parties on the right, but only in Queensland was its support strong enough to win a seat.

On the left, by contrast, the Greens defied expectations by retaining their senators in all six states. Labor at best has won two seats in every state, and its second seat in Queensland is far from certain.

The bottom line is that the Coalition is likely to have thirty-four or thirty-five of the seventy-six seats in the new Senate, up from thirty in the old, meaning it will need either four or five votes from the crossbench to pass legislation opposed by Labor or the Greens.

The existing crossbench of eleven non-Green senators will be whittled down to six: Pauline Hanson and Malcolm Roberts, once again at her side; Cory Bernardi, elected as a Liberal in 2016, only to quit the party immediately afterwards; Stirling Griff and Rex Patrick, the two Centre Alliance senators left from Nick Xenophon’s glory days in 2016; and Jacqui Lambie.

Gone are former Liberal Democrat David Leyonhjelm and his replacement Duncan Spender (New South Wales); former radio and TV livewire Derryn Hinch (Victoria); centrist independent and former Xenophon follower Tim Storer (South Australia); Nationals senator and former Lambie follower Steve Martin (Tasmania); and Liberals senator and former Family First senator Lucy Gichuhi (South Australia).

Also gone are three senators who arrived in Parliament on Pauline Hanson’s coattails: Peter Georgiou (Western Australia), her last loyalist in the current Senate; Brian Burston (New South Wales), who eventually quit to run for Palmer’s party; and, of course, Fraser Anning (Queensland).

Anning’s party stood everywhere and won just 0.6 per cent of the national vote; he himself came last in the four-man battle for Queensland’s final seat on the right, in which Roberts also easily beat Palmer and Liberal conspiracy theorist Gerard Rennick.

Bernardi’s party, which had success in its days as Family First, won just 0.75 per cent of the national vote. Even Palmer’s party won just 2.2 per cent, despite the fortune he spent to win the election.

Hanson’s 5.1 per cent of the vote was less than half the Greens’ tally (11.2 per cent) — but however obvious her limitations, she remains the biggest brand on the right after the Coalition parties. They must be grateful that they do not have a more formidable rival.

7. The battle for Queensland’s final seat is now crucial to Senate control

If the Coalition wins the final seat from Labor in Queeensland, it will have three options for passing legislation Labor opposes: making a deal with the Greens, winning the support of the Centre Alliance and two of the four crossbenchers of the right; or persuading One Nation, Bernardi and Lambie to vote together for the measure.

That makes the battle for the final seat in Queensland crucial. If Labor wins, the Coalition will need support from the Greens or the Centre Alliance to pass legislation Labor opposes; if the Coalition wins, it does not need the centrists on side. As of Sunday, with less than half the vote counted, the Coalition had 2.55 quotas and Labor 1.65.

The Greens (0.82) and One Nation (0.69) both look assured of a seat after preferences. In 2016 both of them won far more preferences than the big parties did. A lot was made of Clive Palmer directing his preferences to the Liberals. This will be the test of whether his voters followed instructions.

And the outcome may help decide how Scott Morrison’s government will govern: on crucial issues, will it seek consensus, or just try to crash through? •