Just a month ago Victoria’s 26 November election was feeling like a kind of tedious duty. It’s a Victorian election, so of course Labor will win — or rather, of course the Liberals will lose. They almost always do. And the opinion polls were suggesting that this victory/defeat could be the most one-sided yet.

In the last three weeks, though, the atmosphere has changed. Victoria’s election has begun to get interesting. The polls, the politics, and the momentum appear to be swinging — not enough to suggest that this election could end Labor’s rule, but enough to make the outcome a bit less certain.

Daniel Andrews specialises in being in control: it’s his thing. Doing press conferences for 120 days straight during the Covid lockdowns was fine with him: the journalists could only ask questions, whereas he could talk as long as he liked without even answering those questions. But he can’t control interviews with thinking radio hosts like Neil Mitchell (3AW) and Virginia Trioli (ABC) who ask critical questions and interrupt him if he goes off on a tangent. So he refuses to face up to them. And in an election campaign, a leader who refuses to appear on the state’s biggest talk shows is a liability to his party.

As the government, Labor normally dominates policy debates. But an election campaign is a more even contest. Both sides have been told by their focus groups that the two key issues for voters are the cost of living and the state of Victoria’s hospitals and healthcare. Both sides are equally able to throw money at any group they think might consider such bribes worth voting for. And both sides are doing so with similar recklessness.

Victoria’s budget is heavily in deficit: even on optimistic assumptions, net debt is heaving towards $165 billion, or 25 per cent of the state’s GDP within four years. The only saving either side has offered so far is Guy’s welcome pledge to cancel the $13 billion Andrews has committed to his “Suburban Rail Loop” (which is not a loop at all). That aside, all the new spending both sides have promised — mostly to shift household costs onto the impoverished state budget and build or rebuild dozens of hospitals — would be funded by further state borrowing, adding to the debt to be repaid by future taxpayers.

It is depressing to watch a once-strong budget being weakened daily by political leaders who lack the courage to make voters pay for what they spend. The long-term costs to Victorians of the Andrews government’s fiscal lassitude in its second term will be substantial. But the spending competition has made the election a more even contest, leaving Andrews for once unable to dismiss the opposition as irrelevant.

Similarly, Labor usually dominates the tactical game, but last weekend it was caught by surprise when opposition leader Matthew Guy announced that the Victorian Liberals would change their preference policy to “put Labor last.” On paper, that’s enough to swing at least two Labor seats to the Greens, even if some Liberals have made it known they don’t like the change.

And the polls are moving, and serving up plenty of variety. Two weeks ago a Resolve poll for the Age found Labor leading 59–41 in the two-party vote. Within days, Newspoll in the Australian declared that lead had shrunk to 54–46. The Financial Review’s new pollster, Freshwater Strategy, put it at 56–44, a Roy Morgan poll reported it as 57–43 (almost unchanged from the last election), while in Monday’s Herald Sun a Redbridge poll put it at 53.5–46.5 — implying a 4 per cent swing against Labor.

What should we make of all that? Take it with a grain of salt. I keep seeing the ghosts of Victorian polls past, such as “Matthew Guy Preferred Premier in Poll as Support for Daniel Andrews Collapses” (2016), or figures during Victoria’s six Covid lockdowns suggesting Labor’s hold had become genuinely precarious. No recent poll suggests that Guy’s Coalition team could win the election.

But there is now a remote possibility that Labor could lose enough seats to lose its majority in the Legislative Assembly — as well as having to deal with a less controllable Legislative Council.

In November 2018, only 22 per cent of Victorians voted for Greens, minor parties and independents. In May 2022, 34 per cent did. That cost Labor no seats at the time, but a repeat of that vote in state electorates on 26 November almost certainly would.

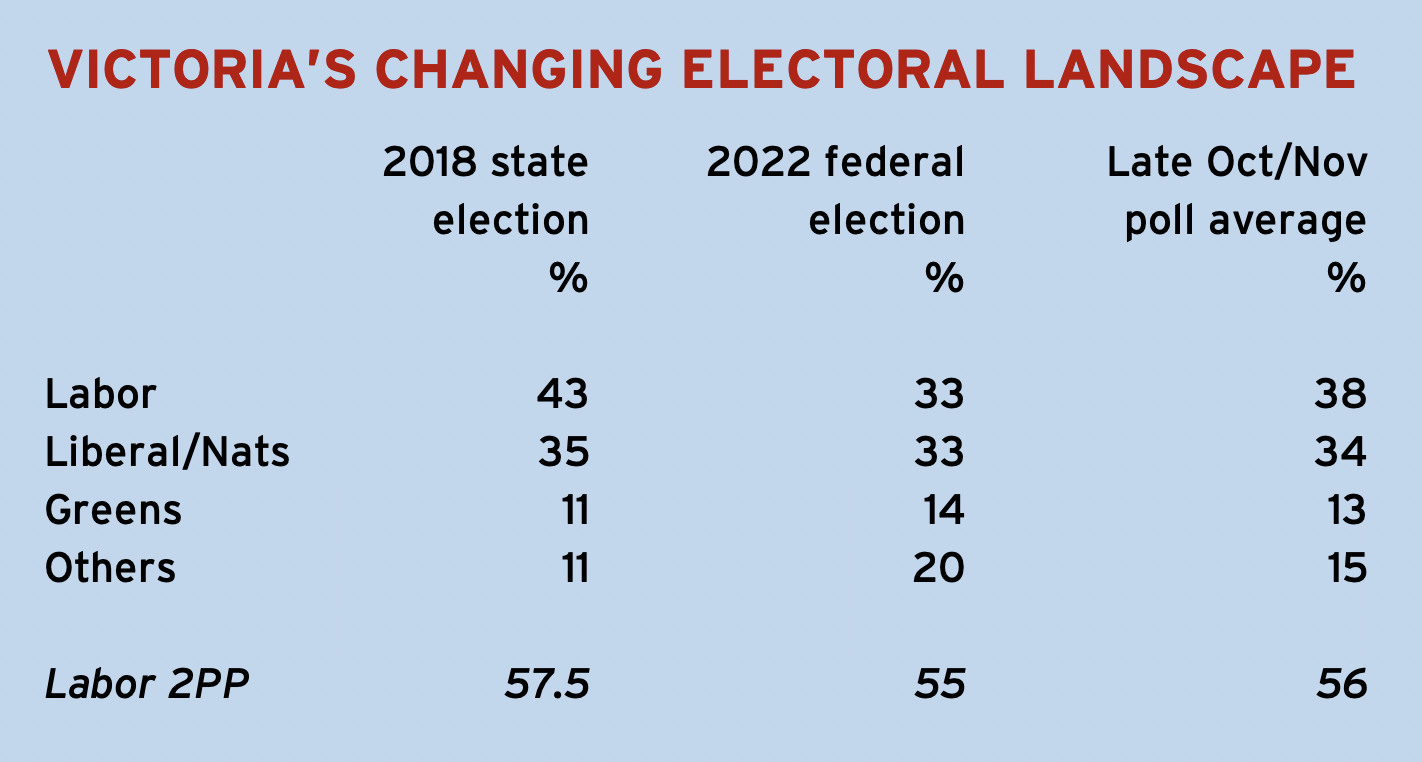

Some numbers might be helpful. Here are three sets of them: in summary form, the votes at the 2018 Victorian election; the Victorian voting at the federal election in May; and a simple average of the five latest polls.

Three things to highlight. First, on the average of the polls, Labor’s primary vote is down 5 per cent since the 2018 election. Yet its two-party-preferred vote is down only 1.5 per cent — and the Coalition’s primary vote is also down, albeit marginally.

What the polls are telling us is that a significant minority of voters are shifting from the major parties — mostly from Labor — to Greens, minor parties of left and right, and independents of all shades.

Even in May, the signs were there. In three-party-preferred votes (that is, Labor v Coalition v the best of the rest), Labor went backwards in two-thirds of its Victorian seats. Even in two-party-preferred contests, competing only with the Liberals and Nationals, Labor lost ground in fourteen of Victoria’s thirty-nine House seats.

Until 2018, the idea of Labor facing challenges in its old working-class seats was implausible. They were rusted on, so it could ignore them with impunity — and did. But then loose coalitions of independents banded together in three of its neglected western suburbs seats to demand similar services to the rest of Melbourne.

Melton, with 70,000 people and growing fast, had no hospital, no TAFE and only an occasional country train service. Werribee was the centre of the booming southwest, where single-lane roads are choked with traffic most of the day. And Pascoe Vale was one of many Labor suburbs repeatedly ignored when the politicians direct their spending promises to marginal seats across town.

None of the independents won in 2018, but they gave the government a scare. In Werribee, treasurer Tim Pallas was fought to final preferences by local GP Joe Garra. In Melton, neuroscientist Ian Birchall came within 5 per cent of winning the seat.

The government briefly acknowledged the western suburbs and made more promises. But four years later, Birchall tells voters, Melton is no closer to getting a hospital, or being part of the suburban rail network, or having its own level crossings removed. You can’t drive around outer northern or western Melbourne without being stunned by the inadequacy of the main road networks their people have to put up with.

Birchall is running again, along with another of the 2018 independents, Bacchus Marsh snake catcher Jarrod Bingham, who in May came third in the new seat of Hawke. Joe Garra has swapped seats to contest Point Cook, but Labor now faces three other independents in Werribee, and more in Broadmeadows, Bundoora, Greenvale, Kalkallo, Kororoit, Laverton, Macedon, Preston, St Albans, Sunbury and Tarneit — as well as in seats in Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong.

They may all lose. For now, the bookies and punters assume that all of them will lose. But the punters got it very wrong in May, when they bet that Labor’s Kristina Keneally would win Fowler comfortably and only one new crossbencher would be elected: Zoe Daniel in Goldstein. In fact she was one of ten.

As of now, the bookies’ odds imply that only five seats will change hands on Saturday week: Labor losing Richmond and Northcote to the Greens, and Hawthorn and Nepean to the Liberals, while holding on to Bayswater (notionally now a Liberal seat after redistribution changed its boundaries). I suspect they might be once again underestimating the likely changes.

Thirteen seats changed hands in 2018, and the Coalition lost eleven of them. It was left with just twenty-seven of the eighty-eight seats in the Assembly. Most of the Liberals’ seats were won very narrowly, with majorities of less than 3 per cent. The overall two-party-preferred vote (including an estimate for inner-suburban Richmond, where an independent Liberal ran after the party failed to nominate) was 57.5 per cent for Labor, 42.5 per cent for the Coalition.

It’s not a good place for the Coalition to start from, and the redistribution has not made it any easier. In Antony Green’s judgement, nine of the twenty-one Liberal seats are held by 1 per cent or less, whereas the vast majority of Labor seats are held by more than 10 per cent. To imagine the Coalition winning this election requires a creativity beyond my powers.

In Green’s view, the redistribution has left Labor with fifty-six seats, the Coalition twenty-seven, the Greens three and independents two. The Labor-held seats of Bayswater and Bass have become notional Coalition seats on their new boundaries, while Liberal-held Ripon and the Latrobe Valley seat of Morwell, held by National-turned-independent Russell Northe, have become notional Labor seats (the more so because Northe is retiring).

Labor will be re-elected for a third term unless it loses twelve or more seats, and there’s no sign of that happening. But Labor won the federal election in May because of a landslide in Western Australia that I don’t recall anyone predicting. If Victorians are hiding their anger from the pollsters, where might it suddenly erupt on election night?

First, we never have a good handle on country seats. The Liberals won Ripon last time by just fifteen votes; it’s possible that they will squeeze home again, despite the unfavourable new boundaries. The Nationals seem surprisingly confident of regaining Morwell, even though it now includes Labor-voting Moe.

And Mildura is facing a challenging election. Not only are the Nationals out to regain the seat they lost so narrowly last time, but seven-time mayor Glenn Milne is running as a conservative independent against its proto-teal independent MP Ali Cupper.

The bookies see two of the seats Labor won in 2018 as low-hanging fruit for the Liberals. Nepean, at the ritzy end of the Mornington Peninsula, voted Labor for the first time in 2018 but came back strongly to the Liberals in the federal election. Former big-serving Davis Cup player Sam Groth is expected to win the seat back for the Liberals.

The biggest upset on election night 2018 was the Liberals’ loss of Hawthorn. Its MP and shadow attorney-general, John Pesutto, spent the night on ABC TV’s panel, gradually realising that he had lost his seat and his job. At least he lost no friends with the classy way he handled the situation, but as the Age columnist Shaun Carney reminded us last week, Pesutto thereby also lost his chance to take over the Liberal leadership and move the party back from the fringes into the middle ground. His loss was one reason why Labor has faced little competition since.

Labor’s candidate John Kennedy, once one of Tony Abbott’s teachers at Riverview, was living in a retirement home at the time, and won preselection only because it was seen as an unwinnable seat. Despite his win, Labor has reportedly excluded Hawthorn from its priority list, opening the way for Pesutto to fight it out with one of just four teal independents at this election, Melissa Lowe, an administrator at Swinburne University.

But to get close enough this time to make a serious bid for power in 2026, the Liberals will need to win back more seats than that. At the federal election in May, their biggest swings from Labor were in the outer suburbs, especially in the new state seat of Pakenham, and in northern Yan Yean, where they had to disendorse their candidate last time. If, as many argue, the Covid lockdowns did most damage to outer-suburban families, many of whom could not work from home, these two seats could be among the casualties.

Labor generally had easy wins in the outer southeast last time, but that was before Covid. Both sides are putting resources into new housing areas in seats like Bass (now notionally Liberal), Cranbourne, Narre Warren North and Narre Warren South.

The Liberals are also hoping to take back some of Labor’s other unexpected gains last time, including the middle-suburban electorates of Ashwood (formerly Burwood), Box Hill and Ringwood, and the outer-south Geelong seat of South Barwon. Ministerial retirements have opened up rare opportunities for them to win back the Dandenongs electorate of Monbulk, held until now by former deputy premier and education minister James Merlino, and the sea-change electorate of Bellarine, vacated by former police minister Lisa Neville.

But Labor’s success in May reminds us that it’s pretty good at looking after marginal seats. It’s the safe seats it often mucks up. And while most of the 129 independents are running in Labor seats, many of them aren’t well known, and virtually all of them will be poorly resourced relative to the major parties, for whom Labor’s electoral reforms carved out a far more generous set of rules than those applied to new parties.

That leaves the Greens as the third opponent Labor has to worry about. But not too much: even with the Liberals preferencing them ahead of Labor, the Greens’ dream result would be to double their seats in the Assembly from three to six.

They first entered Victorian politics at the 2002 election. Amid a Labor landslide, they overtook the Liberals to run second in four inner-suburban electorates — Melbourne, Brunswick, Northcote and Richmond. Liberal preferences helped an unknown young medico named Richard Di Natale to come within 2 per cent of winning Melbourne.

In 2006 they won three seats in the Legislative Council after the Bracks government made a principled decision to switch it to election by proportional representation. (You could not remotely imagine Andrews proposing such a reform.) And when Adam Bandt broke through to win the federal seat of Melbourne in August 2010 — with 80 per cent of Liberal voters directing preferences to him — the state election seemed set for a similar breakthrough.

But Bandt immediately became one of the crossbenchers supporting Julia Gillard. Federal opposition leader Tony Abbott decided to reverse Coalition policy on preferences: he wanted the Greens to be treated as untouchable, which meant giving Coalition preferences to Labor instead. The Victorian election in 2010 was the first under the new policy, and it saw the Greens lose all four contests.

In 2014 the Greens retaliated by targeting a Liberal seat, Prahran, as well as a Labor one, Melbourne. They won them both, despite Liberal preferences in Melbourne going to Labor.

Let’s note: Daniel Andrews and Labor won that election with a majority of just six seats. Had the Liberals not shifted preferences to Labor, the Greens in 2014 would also have won Brunswick, Northcote and Richmond from Labor, leaving it as a government without a majority. Labor would have had forty-four seats, the Coalition thirty-eight, with five Greens and an independent on the crossbenches. Labor would still have formed government, and could have made it work, but it would have required Andrews to develop skills he has yet to show us.

In 2017, future senator Lidia Thorpe won Northcote for the Greens at a by-election. But she lost it a year later at the full election, although her colleague, medico Tim Read, took Brunswick and the Greens just held on to their other two seats, all very narrowly, while Glenn Druery’s machinations saw them reduced to one seat in the Council. Their progress appeared to have stalled.

The federal election changed that, as they became part of the crossbench wave. Their big successes were in Queensland, but their vote surged to a record 13.75 per cent in Victoria, up from 10.7 per cent at the 2018 state election. The Greens came within 0.32 per cent of winning Macnamara (formerly Melbourne Ports) and within 2.40 per cent of winning the three-way contest for Higgins. Had the Liberals preferenced the Greens at that election, Wills and Cooper (formerly Batman) would also have been very close.

The recent polls suggest the Greens’ surge is holding. Their goal for the Assembly is to consolidate their three existing seats, and pick up three more: Richmond, Northcote and Albert Park.

In Richmond they had been held at bay repeatedly by Labor’s veteran MP Richard Wynne, a well-respected former social worker and Labor idealist, and until recently planning and housing minister. But Wynne is retiring, and the bookies already had the Greens as narrow favourites in both Northcote and Richmond before the Liberals’ preference shift made that outcome more probable.

Albert Park is a tougher ask. Alongside Prahran, it makes up roughly half of Macnamara. But while much of Prahran is natural Greens territory, Albert Park is pretty well-off. On my sums, the Greens would need to top their federal election high by another one to two percentage points to win the seat.

The state redistribution did the Greens favours in some other seats, turning Footscray and Pascoe Vale into possible Greens seats in future. But that’s not where this election will be fought.

The single most important fact in Victorian politics is that, for all the mistakes, the polarisation, the high death toll and the policy overkill of 2020 and 2021, the polls make it clear that a majority of Victorians think the Andrews government did a good job in handling Covid. Clearly, he has earned his plaudits as a communicator with voters.

A survey by the Age suggests the voters just want to forget about Covid: old and young voters alike ranked it near the bottom of the list of a dozen key issues. Andrews clearly just wants to forget about it too. Chief health officer Brett Sutton, for so long at Andrews’s side at all those press conferences, has now been dispatched to the “freezer”: the government didn’t even ask his advice before agreeing to abandon mandatory isolation of people with active Covid.

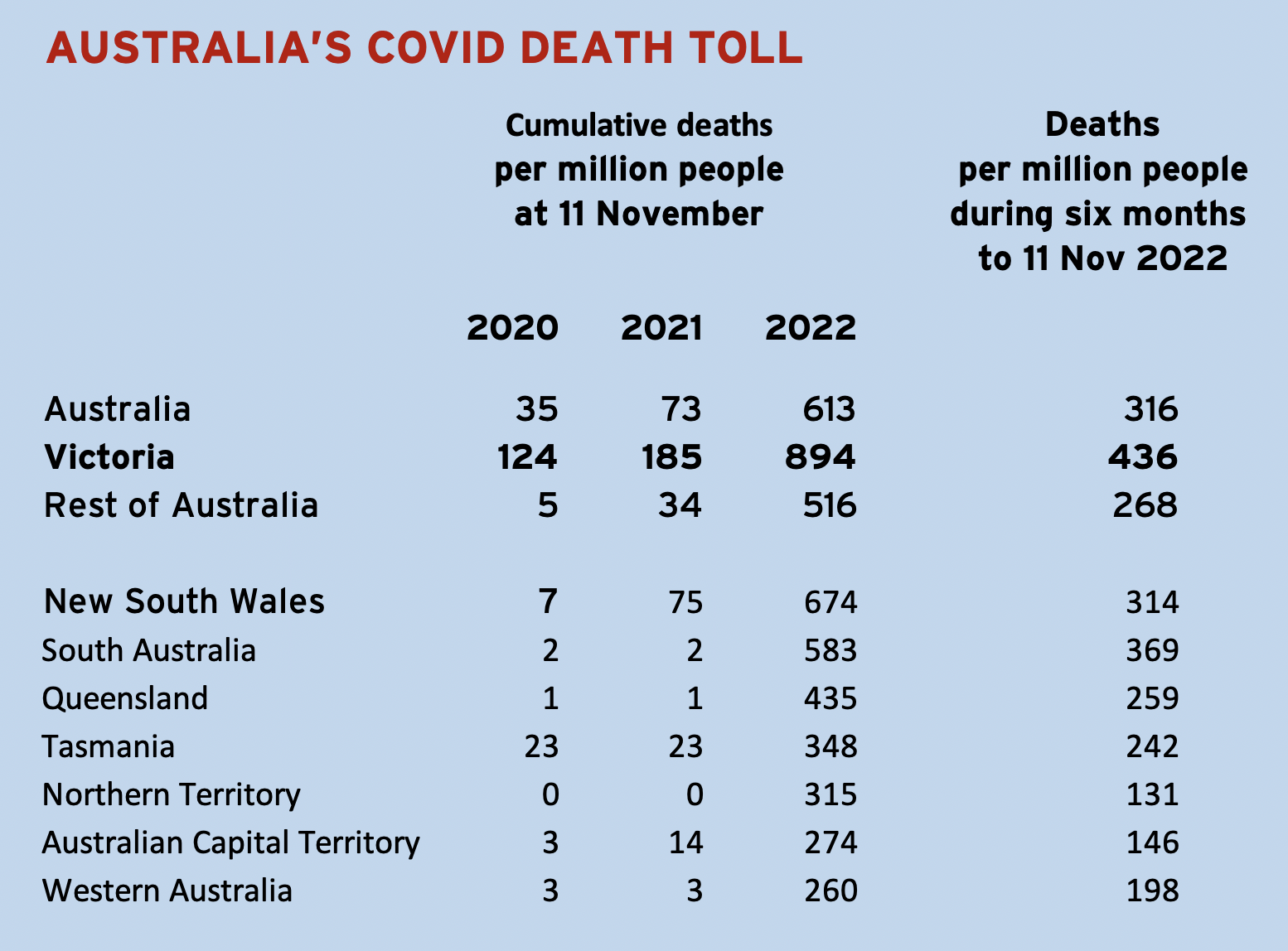

Of course that is a national policy somersault, not just a Victorian one. It is a fact almost universally unreported and undiscussed that most Australians who have died of Covid have lost their lives in the last six months.

Sources: Covid Live, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Victoria is still by far the nation’s worst Covid hotspot: in the past six months alone, it has seen 63 per cent more deaths per million people than the rest of Australia. But to the premier and the voters alike, it seems it no longer matters. They are sick of Covid restrictions, and if old people die of it, so be it.

Andrews’s second term as premier was a lot worse than his first. Fiscal discipline has collapsed, causing an escalation of debt that will make future generations of Victorians poorer. Its symbol is the so-called Suburban Rail Loop, in reality a very expensive twenty-six-kilometre arc underground through Labor seats in the southeastern suburbs. On conventional cost-benefit tests, the auditor-general estimates the cost to Victorians will be twice the benefits they receive.

If Andrews wins a thumping majority on Saturday week, as still appears the likely outcome, what will his third term be like? Sumeyya Ilanbey’s recent biography depicts a leader who thrives on adulation, resents criticism and doesn’t listen to alternative views. His old colleagues have mostly left the room: only four of the twenty-one ministerial colleagues he started with in 2014 still remain.

If there is any constraint on his power in the next term, it could come from the new Legislative Council: the election result we don’t know already. We will look at that later this week. •