IF YOU CLIMB Mount Washington and look over downtown Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle, rimmed by the waters of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers as they merge into the Ohio and flow on down to the great trade route of the Mississippi, it’s easy to understand why President Obama chose this mercurial inland city as host for the G20 summit. And the gods favoured Obama’s choice, gracing the once smoky steel city with two days of September sunlight to glint off its glass towers and throw into high relief the extravagant carved facades of its industrial heyday buildings.

This is the hometown of American venture capitalism, the city where American fortunes were built, so it’s little wonder that the Golden Triangle’s architectural legacy mirrors the ruthlessly competitive history of its titans, men like Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Mellon. “Architectural advertising” is the phrase coined by Franklin Toker, University of Pittsburgh art and architecture historian, to describe the buildings they commissioned, and the phrase is apt. From Mount Washington you can still see them jostling for prominence.

Architectural competition was also a given. The social history of the city these men helped build is so fraught and dramatic it could be Florentine. Frick, for example, fell out with Carnegie after the violence with which he, Frick, put down the Homestead iron and steelworkers’ strike in 1892 (thereby inscribing much of the future of unionism in the United States). That done, Frick built to overshadow his former boss – literally.

But, like me, Franklin Toker wouldn’t want to be without the monumental leavings of these men. On the opening day of the G20 I tried but couldn’t get inside Henry Frick’s 1917 neo-gothic Union Trust building because security guards had barricaded all its doors and humvees blocked the Grant Street intersection. So I walked across the street and craned up in frank admiration of its exuberance, its trefoil ridges and the dormers crowding the roof like so many apostle spoon crests. And if one wanted a complementary history, near Frick’s Union Trust apotheosis of a shopping arcade stands a quite other kind of building, with other ambitions: Henry Hobson Richardson’s Allegheny County Courthouse, often cited as the most distinguished building of nineteenth-century America, or, simply, the best building in America. The plaque inside pays tribute to Richardson in these words: “He left to his country many monuments of art, foremost among them this temple of justice.”

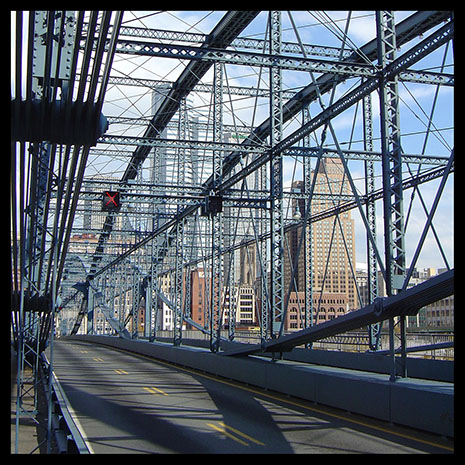

From the street, the courthouse looks Norman and grave. But from Mount Washington its turreted tower remains visible among the skyscrapers, golden in the sunlight. Indeed light might be the symbol of Pittsburgh’s resurgence, from rustbelt town to biotech and savvy twenty-first century city. Sunlight blends its history into a coherent pattern, from the glitter through the cascades of the fountain in Point State Park at the Monongahela and Allegheny “forks” of the Ohio, the place where British, not French, rule of North America was secured, to the light reflecting off the fantasy towers of the PPG building (a corporation once more familiarly known as Pittsburgh Plate Glass), and sliding down the flanks of the David L. Lawrence Convention Center. The Center, built in 2003, and home to the G20, itself symbolises new Pittsburgh, but a Pittsburgh alive to its past as well its future. The Heinz (yes, ketchup Heinz) Endowments sponsored the architectural competition; the winner, Rafael Viñoly, is Argentinian and works out of New York; the Centre has much-heralded green credentials (“the world’s largest LEED-certified building”), while its repeated curves play graceful homage to Pittsburgh’s many bridges (“more than Venice”).

The city has had its ups and downs during its 250-year history, but there is the resilience of a bottom-weighted clown balloon about it: punch Pittsburgh down and it bounces back with a rueful smile on its face. It has needed that resilience because the twentieth century provided an accelerated and repeated pattern of rise and fall. Big steel came and went, as did the wars that steel equipped. The once mighty coke ovens are cold and closed. Conventional manufacturing has largely disappeared. But as my enthusiastic (and hyper-educated – “You must be an official G20 tour guide, surely?” “No ma’am, I just love this place.”) cab driver told me as we emerged from a tunnel into the first sunlit view, “Pittsburgh now runs on eds and meds. That’s education and medical and biomedical research and technology, ma’am.”

He was right. There are so many education institutions, hospitals and research centres in this valley and on the surrounding hills that you think you are in California. But then you are informed that Jonas Salk developed his polio vaccine here, not in San Diego. Just as you are told that Pittsburgh has been home to Rachel Carson, Andy Warhol (the 9th and 7th Street bridges are now named for them), Gertrude Stein, Perry Como, Martha Graham, Michael Chabon, Jimmy Stewart and Gene Kelly. And that’s just the start of the list. So there has been art and music (jazz especially) as well as steel in the Pittsburgh soul – plus the Pittsburgh Steelers won the 2009 Superbowl. Obama knew how to pick a winner.

IN THE MONTHS leading up to the G20, and in the days before and during the international invasion, the city and neighbourhoods (which are the social lifeblood of Pittsburgh) became enthusiastic, if nervous, hosts. This is a working community, not tolerant of “layabouts” or “out-of-town” demonstrators, particularly if they wear anarchist black or flout the rules. But Pittsburgh is proud of its town and its hospitality, so when Burmese monks marched in orderly fashion down Liberty Avenue on the Thursday they got a warm reception from the people who live and work in this newly revived cultural district (a redlight precinct only a few decades back). Even the squads of armed and armoured police lining the march route were genial and intrigued: “Whaddya reckon they dye their robes with?” “Saffron, mandarins and some other stuff.” So intrigued, in fact, that it was hard to get directions from them. Many were from out of town anyway: “Sorry ma’am, can’t tell you where Sixth Avenue is. I’m from Phoenix, Arizona.”

Some Pittsburgh Post-Gazette commentators and riled citizens insisted that the security surrounding the event was oppressive, excessive, un-Pittsburgh. It was certainly comprehensive: the Convention Center security was so tight that even local journalists were arrested (temporarily) simply for being in the vicinity. Many of the bridges were closed. The rivers were empty of all traffic except US coastguard vessels. The chipboard manufacturers must have made a killing because so many downtown buildings had their plate glass boarded up. I particularly enjoyed “Catholic Charities, Diocese of Pittsburgh,” which was locked and comprehensively clad, and “Alpha Graphics – Copy Print and Communication” which had “Welcome to the World” all over its shopfront, pasted on top of the chipboard keeping its windows safe. Almost as much fun were the Port Authority buses, also rolling out their digital “Pittsburgh Welcomes the World” greeting as they sat in gridlock on Fifth Avenue while national guardsmen in camouflage gear checked and strolled and sat and looked.

I rode out to Oakland on one of those buses just as Kevin Rudd was giving his well-received Thursday address at Carnegie Mellon University. “Rudd calls for reform of ‘debt-driven’ economics” was the headline in Friday’s Post-Gazette, and the sixteen column inches devoted to his views were given prominence over the commentary on Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and European Commission President José Manuel Barroso. The Post-Gazette perhaps enjoyed Rudd’s self-description as a “nerd.” Certainly they appreciated his recent twitter posting about victory by the Broncos (“no worries, mates, he’s referring to the Brisbane Broncos rugby footballers, not those guys from Denver.”)

There were some scuffles in Oakland, and subsequent complaints about unnecessary police violence. On the bus I met some of the protesters – kids, all gingered up. Their leader, a Brad Pitt lookalike in strained blond dreadlocks, kept mouthing into his mobile: “Just check the website. It’s resistg20.org, that’s r-e-s-i-s-t-g-20.” One of the wide-eyed girls asked if I could tell them where to get off. She was from Colorado and, as it happened, I could. We both needed the stop near Pittsburgh University’s Cathedral of Learning. Yes, that is what the tower is called, and it’s 535 feet high. This, in the city that also has a building-size mural of Andrew Carnegie and Andy Warhol seated together, in rollers, under hairdryers that look like guided-missile cones. Carnegie is soaking his fingers in two manicure bowls. Warhol is gazing quizzically. The mural isn’t as tall as the Cathedral of Learning, but it speaks volumes. It’s very hard not to like Pittsburgh.

It was also hard to learn much about Pittsburgh, or even the G20, in the weeks leading up to the summit. If you live on the east coast as I do and read the New York Times, or even the Washington Post or the Wall Street Journal, you’d have to do a fine comb to find any reference to anything much happening anywhere beyond the Washington Beltway, New York State elections or international politics. Healthcare, yes, every day (and more bizarre insanity every day in the resistance to the public option); Iran, most days, and extensively at the United Nations and just before the summit, when Iran was forced to confess about the new enrichment site. Fashion week (bondage shoes featuring extensively) has been better covered in the media than preparations for the G20. But that’s America. You know that behind the scenes the professional political business, the horse-trading, the press releases and communiqués will have been thought through and tailored down to the last dot. Just don’t try to extract that kind of detail from the media. The cabbie who picked me up back in Philadelphia asked where I’d been. “In Pittsburgh, for the G20.” “Uh huh. Great. What’s the G20?”

He’ll probably never find out, though he’d learn a lot, and in readily digestible form, if he were to search out the distillations of the two economist-reformers, Joseph Stiglitz and Jeffrey Sachs, who both wrote lucidly and with the requisite long perspective, in columns published and no doubt syndicated during the summit period. And while world leaders were packing and catching planes to the presidential reception, Joseph Stiglitz was talking to all comers at the Monumental Baptist Church, in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. This is not the Pittsburgh that appears on the G20 websites or the city promotion brochures. This is a neighbourhood that has yet to feel the full benefit of Pittsburgh’s latest renascence. Its vacant blocks, remnants of 1960s civil strife, and now anomalously abloom with the delphinium-flowered weeds that make devastation look bucolic, are yet to be reclaimed. There is a new Carnegie library down the hill from the church, and it is eagerly patronised by women with children in strollers. But there is so much still to be done, so much to be recovered.

I went up to the Monumental Baptist Church on the Friday morning for an advertised “G20 round up.” It consisted mostly of an open-air thank you to the “Bail Out People” organisers who had put the case of the homeless or unemployed to all who would listen during the summit. Next door, in the church, a funeral was in progress. The folk who walked into the church were the best dressed I’ve seen during my time in America – seemly, dignified. The young activists from the impromptu tent city on the vacant block next door looked a bit worse for wear, but buoyed up. “Nothing violent,” the organiser told me. “We were worried when they arrived that there’d be trouble, there’d be police. But nothing happened. They were great.” The Reverend Tom Smith from the Monumental Baptist Church was cheered and thanked for his outdoor hospitality. His vacant block has one of the best views in Pittsburgh, best in many ways. One lad told me he was driving back to Florida that day – and he’d “stay committed.” As I left, another young man, this one immaculate in a red bomber jacket (where had he showered?) set up his laptop on a green plastic milk crate and tapped away.

Barack Obama was strategic in his choice of Pittsburgh and Kevin Rudd was diplomatic in his description of the city’s transformation as a potent sign of hope in this time of economic crisis. Rudd can hardly have met many Pittsburghers, but then neither had I until a few days before, and he was right to call them “resilient, adaptive and creative.” These are traits that mark Pittsburghers’ history and their present, and they are evident still in what its people do today as they ride their bikes on newly built trails (you can cycle all the way to Washington if you so choose, so maybe Pittsburgh could adopt the Paris cycling model and make city bikes available to all); as they reclaim old factories and warehouses with the tools of the twenty-first century, build research facilities, hospitals, schools, and reclaim disused factories for art galleries, sometimes with grants from the “old” money of Pittsburgh, sometimes with taxes. The Mattress Factory, a new-old gallery on the North Side, located in the middle of a complex of modest residential streets named for the heroes and battle sites of the Mexican Wars, finally made sense of installation art for me, with the best works, by James Turrell, I have seen anywhere in the world.

But it was the young woman, a Pittsburgh local, who welcomed me into the deserted gallery (“We’re having a pretty slow day with the city all locked down for the G20”) whom I’ll remember as much as Turrell’s luminous red and blue rooms. It was she who told me to take my time because those dark spaces could be frightening at first and some folk lose their balance. It was indeed dark, and it took me nearly half an hour to adjust my eyes and brain to a vivid new experience.

FRANKLIN TOKER, Pittsburgh chronicler as well as art and architectural historian, says he believes that people become attached to a city that they can see. I thought of the surge of – what – exhilaration? pride? – felt every time I cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge, or, indeed, catch the first sight of the Manhattan skyline from Newark (and I was born in Adelaide). Pittsburgh, surrounded by hills that house most of its people, can always look down and see its civic self and the sublime terrain out of which it has been forged. It must have looked extraordinary when the flames from the coke furnaces and steel mills lit the night skies and clouded the daytime air. Now it has a different aspect.

Pittsburgh is in the process of taking stock – of the raw resources beneath its ground, of the waters that flow around and through it, of its air, and of the wits of the people who have built and rebuilt and built it again. If the international delegates to the G20 summit had their eyes and minds open in Pittsburgh they will have seen things – tangible and intangible – worth taking back to the world. •