If the polls are right, Saturday’s Victorian election is shaping up as one might have expected, given the polarisation of Victorians over the Andrews government’s handling of the Covid pandemic. Labor is forecast to lose votes, and seats, but not government.

That’s not enough for the Murdochs’ Herald Sun, which has been whipping up its rusted-on older conservative readership with stories quoting fearful Labor insiders’ predictions of gloom: “Toxic Dan: ALP Fears Voters Are Turning against Andrews,” “Sign Dan Could Lose Mulgrave Seat in Shock Upset” and, today, “Dan Faces Minority Govt as Voters Turn against Labor.”

But I would take that less seriously than the polls. I’ve never heard an insider in the final week say, “We’re home. We’re going to win by a mile.” They are paid to worry. They always pretend it’ll be close. They did it in 2018, when Labor won twice as many seats as the Coalition.

By contrast, the polls tell us the contest is narrowing, but Labor remains well ahead and Daniel Andrews is still far more popular than Matthew Guy; and no poll has yet shown the Coalition remotely within reach of winning. The polls can be wrong — in 2018 they all understated the scale of Labor’s landslide — but my instinct is that this time they’re probably close.

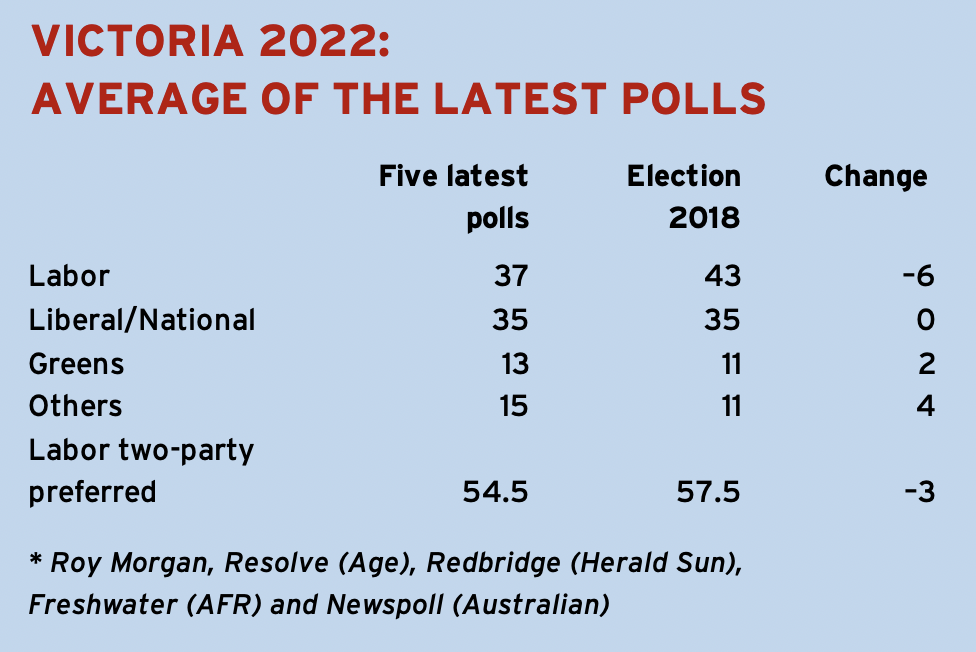

On the average of the last five polls reported in the media, Labor’s vote is down from 43 per cent in 2018 to 37 per cent, the Coalition is unchanged on 35 per cent, the Greens have edged up from 11 to 13 per cent, and “others” — independents and micro-parties — have jumped from 11 to 15 per cent. (That’s partly because there are far more of them, almost three times as many micro-party candidates as in 2018, and mostly running to the right of the Liberals.)

In two-party terms, the average implies a swing to the Coalition of three percentage points or so, taking Labor from 57.5 per cent to 54.5 per cent. That would normally be a very safe lead — but this election is not just between two parties.

In this morning’s Herald Sun, former Labor assistant state secretary Kos Samaras, now director of the pollster Redbridge, forecast that Labor would lose six seats and is in danger in a dozen others. But only half of those are battles between Labor and the Coalition. On his reading, Labor is in danger of losing up to five seats to the Greens, and up to four seats to independents.

The punters half-agree. They don’t see many seats changing hands, but of the twenty-five electorates Sportsbet rated on Wednesday as the closest contests, three are Labor v. Green, four are independents v. Labor, five are independents v. Liberal, and two are independents v. National (including one that is shaping as independent v. National v. independent). Fewer than half are classic Labor v. Coalition contests. (I covered this last week.)

If Samaras is right, then Victorian Labor might lose its majority and have to learn how to share power in some form with the Greens or independents. Labor and the Greens have been doing that in the ACT for most of the last two decades, and it’s been quite harmonious. But Victorian Labor will also face the big unknown of a new Legislative Council.

Ah, the Legislative Council. Until the 1950s, it was a conservative bastion, elected by property owners to be a brake on hasty populist reforms. (It sure was: it took almost twenty years and nineteen private members’ bills before the Council agreed that women should have the right to vote.) It was a part-time chamber where gentlemen gathered in the evenings to debate the issues of the day. Most Victorian adults were excluded from the Council’s voting roll, and most MLCs were elected unopposed.

These days it’s so different. Since 2006 the chamber has been elected by proportional representation, with preferences decided not by voters but by backroom deals via group voting tickets, like the Senate elections of old. Even a decade ago, the Council’s only crossbenchers were three Greens. But at the 2014 election, “preference whisperer” Glenn Druery orchestrated the election of five crossbenchers from small parties — and in 2018 the forty MLCs elected included nine of Druery’s team plus a rebel breakaway, Fiona Patten.

There are eight regions with five members each. The quota for election is 16.7 per cent, yet those nine Druery members on average won just 3.4 per cent. Druery’s system works by getting ideologically diverse parties to direct preferences to each other, in effect pooling their votes — and then doing trade-offs with the major parties to get them to do the same. The preferences are arranged so that every party gets a seat or more — or at least, the chance of one.

His system works because Victorians have no control over their preferences unless they vote below the line — which last time only 9 per cent did. Voters below the line only have to number five boxes or more, far easier to comply with than the rules in the Legislative Assembly, where votes in seats like Point Cook and Werribee will be declared informal unless voters have numbered all fifteen boxes in order. Our ignorance and indifference let Druery and party bosses decide our preferences for us.

In 2018 this system led to many results seen as unjust. In Eastern Metropolitan, Greens MLC Samantha Dunn won 9 per cent of votes, yet lost her seat to taxi owner Rod Barton of Transport Matters, who won 0.6 per cent. In South-Eastern Metro, Liberal MLC Inga Peulich, with 12 per cent of the votes, lost her seat to Liberal Democrat David Limbrick with 0.8 per cent. And in Southern Metropolitan, Greens MLC Sue Pennicuik, with 12 per cent, was unseated by Sustainable Australia’s Clifford Hayes with 1.2 per cent.

In Western Australia, the last state apart from Victoria to tolerate this system, the McGowan Labor government has moved to abolish group voting tickets after the last election saw Daylight Saving Party candidate Wilson Tucker, then living in the United States, win a seat in the outback region with just ninety-eight votes. But the Andrews government has shown zero interest in electoral reform.

Why not? Because it sees this system as working in its favour — and at the 2018 election, Labor was effectively an associate member of Druery’s team. Its preferences were directed to Druery parties in six of the eight regions, and in four they helped elect parties as diverse as the Liberal Democrats, Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party, Animal Justice and Transport Matters.

The losers in 2018 were the Greens, who went from five seats to one, and the Coalition, down from sixteen seats to eleven. Its election landslide gave Labor eighteen of the forty seats, close to a majority, and it could recruit enough allies issue by issue to pass its bills. The Age reported last year that its most reliable supporters were Animal Justice MLC Andy Meddick and Fiona Patten, followed by Rod Barton, and the one Greens MLC who survived Druery’s rampage, Samantha Ratnam.

The other six MLCs elected on Druery’s tickets have all voted mostly against Labor. One is from Sustainable Australia, two from the Liberal Democrats, and originally three from Hinch’s squad, one of whom, former Maribyrnong mayor and army reservist Catherine Cumming, soon quit the party and is now running for the Angry Victorians. (She was the one who told a rally last weekend she wanted to turn Daniel Andrews into “red mist” — a politicised play on the army term “pink mist” for the spray of blood on the face of the victim of a shooting.)

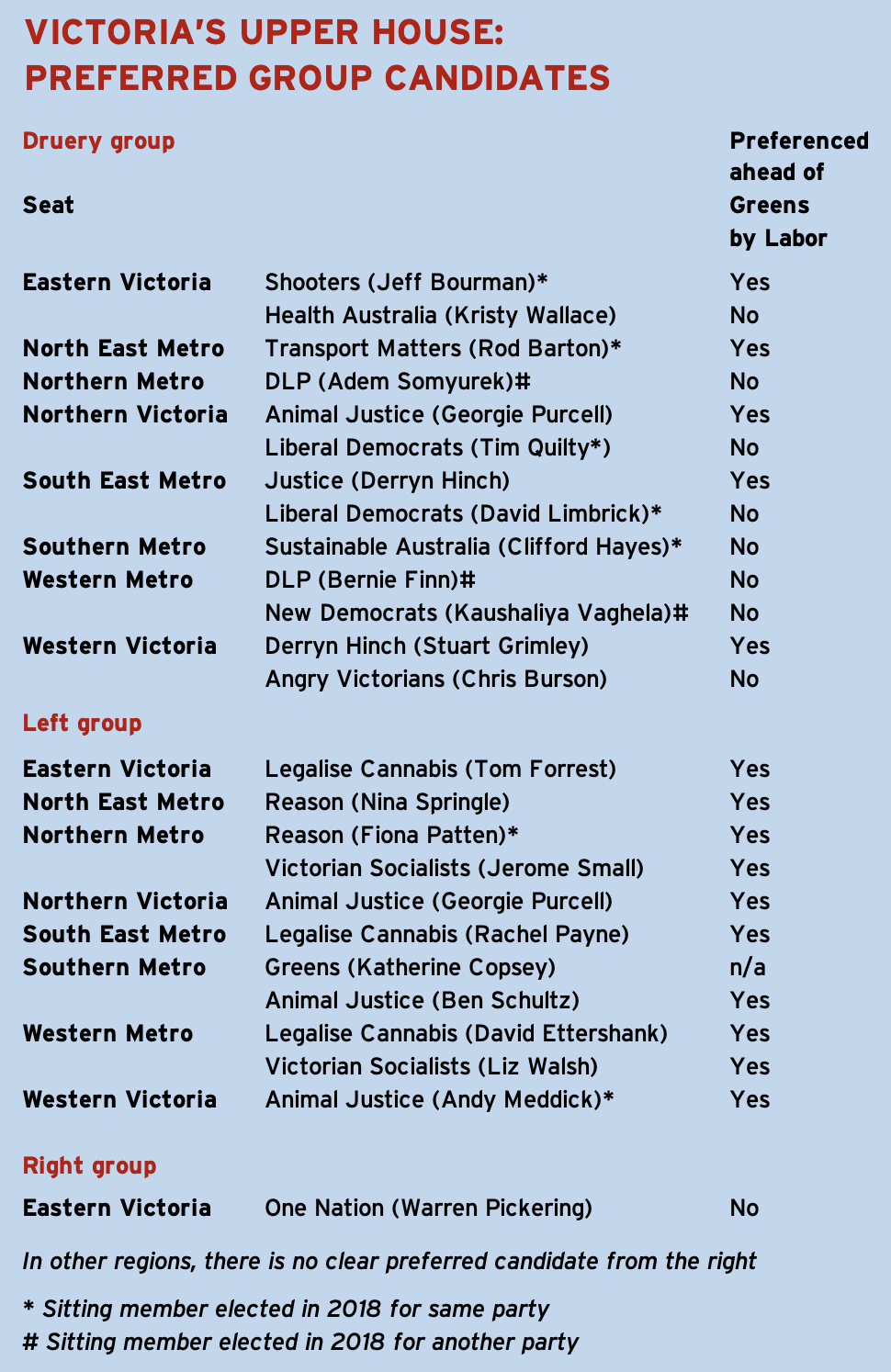

For this election, the Druery team consists of just eight core parties: the DLP, Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party, the Health Australia Party, the Liberal Democrats, the New Democrats (a party founded by rebel Labor MLC Kaushaliya Vaghela), the Shooters, Sustainable Australia and Transport Matters. All but Health Australia have sitting members — in the DLP’s case, sacked Liberal ultraconservative Bernie Finn in Western Metropolitan and sacked Labor powerbroker Adem Somyurek in Northern Metropolitan — and their priority is to retain those seats.

On the fringes are four other parties. Angry Victorians and the new party calling itself Sack Dan Andrews Restore Democracy in the end stayed out of the group, but their group voting tickets largely reflect its priorities. Animal Justice is now a former member. And Labor remains an unofficial associate member, but more distant than in 2018.

In 2022, Team Druery’s prospects are not looking good. It faces unprecedented opposition from the left and right alike. The Liberals, Greens, One Nation and United Australia Party all effectively refused to deal with it. Four smaller left-wing parties organised their own version of Druery’s system, and got Labor and the Greens to direct their initial preferences their way in every region. And some parties it thought were on board refused to sign up.

The worst betrayal was by Animal Justice. Elected with Druery’s help in 2018, it pretended to be part of the team again, and was awarded the group’s preferences in two regions, Northern Victoria and Western Victoria. But it hid the fact that it had joined the new left-wing alliance, and is directing its preferences there. This became known only when its real group voting tickets were released.

The second betrayal was by Angry Victorians. It is giving Druery’s parties high preferences in all regions, and has been rewarded by the group giving it high preferences in Western Victoria, where its leader Chris Burson is standing. But it gave the Herald Sun a secretly filmed video of a long chat with Druery in which he boasted of his power to select MPs and told them his aim was to create a Council that Labor could work with. (He was talking to the wrong people on that one.)

Labor is still a Druery ally, but its preferences at this election are going first to the left-wing alliance. Their combined preferences should ensure that in Northern Metropolitan, Fiona Patten will either hold her seat or lose it to the Victorian Socialists. Animal Justice’s double dealing has probably wrapped up seats for it in Northern Victoria and Western Victoria. The Greens look set to win back their lost seat in Southern Metropolitan, and possibly several others. But in some seats, the left’s alliance has fractured.

There was a plan that, to maximise the left’s haul, Labor and the Greens would also preference each other. But something got in the way of that. Instead, Labor will direct its sixth preference to the Shooters in Eastern Victoria, to Transport Matters in North-Eastern Metro, and to Derryn Hinch in South-Eastern Metro — and, of course, its second preferences are going to Animal Justice in Northern Victoria and Western Victoria (where Hinch and the Shooters will also get Labor preferences before the Greens).

All of them are (or were) the primary candidates of the Druery group in those regions. Clearly, Labor is still part of the team.

Spurned, the Greens have directed preferences to Transport Matters ahead of Labor in every region, but realistically, that has no effect: in North-Eastern Metro the two parties will be rivals, and Transport Matters will be quickly eliminated everywhere else.

What does Labor get from Team Druery in return? Well, the Shooters have taken the unusual step of giving Labor their second preferences in the marginal seat of Morwell, as well as in Narre Warren North. Hinch nominated candidates in some of the Assembly seats Druery claimed Labor was worried about, but after the betrayals, he appears not to have registered how-to-vote cards.

Then there is a curious deal in Northern Metropolitan. Three of Druery’s parties are giving their second preferences directly to Labor’s number three candidate, Susie Byers. Why? Well, if the votes go as they did in 2018, she would be the one competing for Fiona Patten’s seat. Druery has never forgiven Patten for deserting his team and telling the world that he charges candidates a success fee of $50,000. And Labor has never forgotten that it is their old seat that Patten occupies.

You could be forgiven for thinking that Labor and Druery are combining to try to unseat Patten, even if Labor is also directing its preferences to her. But that assumes the voting at this election will be something like 2018. It won’t.

In 2018, Labor won 39 per cent of votes for the Council. In May 2022, it won just 31 per cent of Victorians’ votes for the Senate. If its vote is like that on Saturday, it could lose up to six seats in the Council, maybe even more.

By contrast, votes for the Greens and the minor parties of the left (including Legalise Cannabis, formerly HEMP) jumped from 12 per cent to 20 per cent. They stand to gain the seats Labor loses. There is no certainty that it will find all of them as easy to deal with as Animal Justice and Reason.

In 2018, Team Druery consisted of thirteen parties and won 20 per cent of votes. In May 2022, only four of its current members contested the Senate election, and they won 5.6 per cent of the vote. Of the other four, only the DLP has any proven following, and it’s pretty small these days.

Outside both groups are the other right-wing parties. One Nation and the United Australia Party are continuing their alliance, which helped the UAP win Victoria’s final Senate seat from the Liberals. But in contrast to the federal election, they have been inconspicuous in this campaign. Palmer’s party stands to get preferences from the Liberals in most regions, but with few others coming its way, it’s hard to see it being a strong contender. One Nation has a chance of winning a seat in Eastern Victoria, but generally its Victorian base is limited to the country.

The new Freedom Party has a preference deal with Family First, and a more limited one with One Nation, but by and large the minor parties of the right look uncoordinated compared with the tight preference deals of the left and the Druery group. It’s surprising that most of them appear to have no preference swaps at all with the Druery camp — whose largest members are the Shooters, the Liberal Democrats, the DLP and the Hinch party. I suspect they will win few if any seats.

But it’s really anyone’s guess who will win the final seats in each region. One dark horse: at the Senate election, the biggest small party on the left was Legalise Cannabis (formerly HEMP). It won 3 per cent of the Victorian vote, outpolling One Nation. It’s got its share of preferences coming. It’s got a pretty simple policy. A lot of people agree with it. For those who hate all politics and politicians, it could be an attractive alternative.

As you can probably tell, I have no idea who will control the new Council. We will find out very late on Saturday night. Those with a keen interest in the outcome can try out their tipping skills on Antony Green’s election calculator, but it’s more useful after the event.

There has been a buzz this week in the betting markets, picking up on the fears of Labor insiders. Even so, the Coalition’s odds of forming a government have shortened only from 10/1 to 5/1: giving it at best one chance in five of victory, and four chances in five of another term in opposition.

For what it’s worth, the punters see just five seats clearly changing hands. Labor is tipped to lose Richmond and Northcote to the Greens, Nepean to the Liberals, and Hawthorn to either the Liberals or teal independent Melissa Lowe. The Liberals in turn are tipped to lose Kew to teal independent Sophie Torney.

A lot of seats are seen as being on a knife edge: Bayswater, Glen Waverley, Morwell, Pakenham and Ripon between Labor and the Coalition, Melton between Labor and independent Dr Ian Birchall, Benambra between the Liberals and independent Jacqui Hawkins, and Caulfield between Liberal, Labor and another teal independent, Nomi Kaltmann. The Coalition would have to do a lot better than that to pose any threat.

But the punters can get things just as wrong as the pundits. In 2018, as now, they tipped just five seats to change hands. Yet only one of those five did, whereas twelve seats they hadn’t tipped to change hands did so.

To lose its majority this time, Labor would need to lose twelve of the fifty-six seats it has on Antony Green’s pendulum. To win a majority, the Liberals and Nationals would need to win eighteen seats on top of their current twenty-seven. Both sound improbable, but stranger things have happened. •