A Bigger Picture

By Malcolm Turnbull | Hardie Grant | $55 | 704 pages

If you have an aversion to alpha males with gargantuan egos blowing their own trumpets for hundreds of pages, saturating you with sanctimony about their own motives yet finding only the meanest for others, and smiting their enemies — the bitterest invariably on their own side of politics — while finding the explanations for personal failure in the weakness or treachery of colleagues, Australian prime ministerial memoirs are not for you. Certainly not Malcolm Turnbull’s A Bigger Picture. The mellow mood of Robert Menzies’s Afternoon Light and The Measure of the Years doesn’t belong just to another era but also, in essence, to another genre.

Turnbull remains one of the great puzzles of Australian public life. This book does only a little, at least consciously, to clear that matter up for us. Unconsciously, it’s rather more revealing: for, as his former business partner Nicholas Whitlam has suggested in the Weekend Australian, it’s a deeply evasive book in places. But its evasions are more meaningful than the “revelations” that have been the subject of many a sensational media article in recent days — and much more so than the sensational text messages, diary entries, WhatsApp conversations and all the rest on which Turnbull draws to provide his insider’s account.

This reader’s sensation was often that of a member of a jury being addressed by a skilled if not entirely scrupulous barrister. But there are also hints of a hard sell. By the end of the book’s almost 700 pages, I felt like someone trying to get away from a pushy salesman determined to press the latest mobile phone on me.

Turnbull, of course, has been on sale since the 1980s, and his particular blend of skills has invariably drawn a good price in the market. Kerry Packer saw his value early, and Malcolm didn’t let him down when, as the “Goanna,” the multimillionaire was subjected to allegations of criminality arising from the Costigan royal commission. Turnbull thinks he discredited Frank Costigan, but he was really just the paid advocate of a bully whose habit of keeping millions stashed in his office safe understandably aroused suspicion. Costigan, after all, had already found Australia’s wealthy elite riddled with clever crooks, many of whom were none too fussy about going into business with waterfront thugs in their efforts to avoid paying tax. But the young and ambitious Turnbull was clever enough to turn his defence of Packer into a civil liberties crusade and his role as Packer’s counsel into hot personal PR.

Turnbull also did much for his public profile in the case against the Thatcher government’s efforts to stop publication of that excruciatingly dull and thoroughly paranoid cold war memoir, Peter Wright’s Spycatcher. Turnbull, tender about Packer’s reputation, seems unworried that the book’s central claim — that MI5 chief Roger Hollis was a Soviet mole — was almost certainly false. But then Hollis was dead and, unlike Packer, didn’t have Turnbull on a retainer. Once again, Turnbull was the great crusader for right against might; in his summing up during the trial, he compared the cause of publishing Wright’s miserable book with the struggles of Australia’s shearing unions in the 1890s, a topic on which his mother, Coral Lansbury, had written.

It’s no surprise to find that there are plenty of actors in the family; Angela Lansbury is a relative. The account of his childhood is a mixture of nostalgia and pain — born before his parents wed, he was the product of a doomed marriage of ill-suited partners. The absence of his beautiful and talented mother, a writer for radio, is at the heart of the early part of the book, even while Turnbull seems to go out of his way to make it otherwise: “I don’t think I could have been any closer to Coral, nor do I think she could have been a better or more attentive mother.” Except that she leaves. And then she arranges for the furniture to follow her to New Zealand, where she had moved with a new husband, her third. Malcolm is told that she was merely studying for another degree over there; his father failed to inform him that his mother wasn’t coming back. “So, her absence crept up on me, like a slow chill around the heart,” he recalls.

But that’s almost the last we hear of Lansbury, who made an academic career in the United States: I suspect that the chill didn’t disappear any time soon, if ever. Turnbull provides an affectionate portrait of the father left behind, who was a bit of a lad, more like an older brother. But Bruce Turnbull scraped together the money to send Malcolm to Sydney Grammar as a boarder, which young Malcolm at first hates, because he is a bedwetter and is bullied. He eventually flourishes under the guidance of inspiring teachers.

Young Malcolm liked history and recalls writing an essay on Cosimo de’ Medici. That might explain a little: Cosimo was a Florentine banker, founding member of the dynasty that effectively ruled Florence, and a patron of the arts, architecture and scholarship. His indictment in 1431 accused him of “having sought to elevate himself higher than others.” Imprisoned for a time, he later made a triumphant return to political rule, becoming the city-state’s grand and visionary statesman. Any of that sound familiar?

When the artist Lewis Miller accepted a commission in the early 1990s to produce portraits of Malcolm and Lucy Turnbull, he decided on a homage to the Renaissance portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino by Piero della Francesca, held in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. An unimpressed Turnbull apparently thought that the resulting painting made him look like a “big, fat, greedy c—t.” (Ray Hughes, the Sydney dealer who arranged the commission, valiantly defended the artist by explaining that Miller was a realist painter.) But it’s hard to shake off the feeling that Turnbull has modelled himself on his image of a Renaissance-era Italian merchant-statesman, right down to the republicanism and the landed estate outside the city walls (actually, in the Upper Hunter).

Still a student at the University of Sydney, Malcolm is already doing political journalism for print radio and television. Like Paul Keating, he sits at the feet of old Jack Lang, and is attracted to “the romance and history” of the labour movement — presumably, in large part, through his mother’s influence — while always feeling like “a natural liberal, drawn to the entrepreneurial and enterprising.” With a good private school education behind him and an abundance of talent, energy and ambition, life now seems like pretty smooth sailing; opportunity just falls into his lap. He attends an Oxford Union debate while on a trip to England and speaks from the floor on the importance of a free press. Sure enough, Harold Evans, the Sunday Times editor, is present and sends him a note asking him to drop by in London. When he does, the next day, Evans immediately offers Turnbull a job, which he declines so he can finish his law degree back in Sydney. But there is a handy connection for the future. Life is sweet.

The run of luck continues. Back in Sydney, Turnbull turns up to write a profile of barrister Tom Hughes; he ends up marrying his daughter, Lucy. Soon, he is working for Packer, travelling the world signing up the West Indies team to World Series Cricket and arranging the Australian licence for Playboy. Then there’s a Rhodes Scholarship — although not on his first application — and a good degree from Oxford, despite his spending much of his time mucking about in journalism in London in the middle of a printers’ strike at The Times. The young man who admires the romance and history of the labour movement now tries to line up a deal that would have Packer come in, take over Times Newspapers, and break the unions. It is already clear enough that the cause dearest to Malcolm’s heart is Malcolm. There is no mention of the shearers’ unions on this occasion.

Tragically Bruce Turnbull, now a wealthy and successful hotel-broker, is killed in a light-plane accident soon after Malcolm returns to Sydney. Malcolm is now married, the owner of a Hunter Valley property inherited from his father, and a member of the bar; but what will Malcolm do with his life? He is not shy of aiming high. His “ambition was to get to the top of the profession and equal, if not excel, Lucy’s father.” It is a revealing way to frame one’s ambitions: to better one’s wife’s father, who was possibly the country’s leading barrister and a former federal attorney-general.

By the time he is forty, Turnbull has achieved his dream of financial independence. When he moves his family into a massive and luxurious waterfront mansion in 1994, he says that he has achieved what his father had always told him would be “the ultimate home”; fittingly, it overlooks the block of flats in which his father raised him. But interpreting such material is a job for Dr Freud and his followers, and not for an old-fashioned historian such as this reviewer.

Malcolm really begins to rake in the millions as a merchant banker in the late 1980s. His speciality is restructuring media companies, which are all over the shop in the wake of new media laws, the recklessness of some of the business figures involved — including Alan Bond, Christopher Skase and (Young) Warwick Fairfax — and the market and financial turmoil of the era. Turnbull falls out with Packer in the battle to control Fairfax, but Packer has already cheated him, so that’s okay. From there, it’s an even bigger fortune as an IT entrepreneur with OzEmail, and various dealings in mining and forestry in out-of-the-way places like Siberia, China and the Solomons, which are all aboveboard and environmentally friendly — nothing to see here.

Next, he closes his investment bank and joins Goldman Sachs, becoming managing director of its Australian operations. Paddy Manning’s biography of Turnbull points out that Turnbull became a partner in the firm just before it listed on the New York Stock Exchange. His new shareholding is likely to have added tens of millions to his wealth: one estimate put it at $70 million at the time Turnbull left the bank in 2001, much more than he made from his OzEmail investment. None of this is mentioned in A Bigger Picture. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that this particular evasion is better for the image Turnbull wishes to present in this book of a far-seeing, cutting-edge IT entrepreneur rather than the remarkably fortunate recipient of an enormous windfall.

Inconveniently — because he is moving, inexorably, towards a political career — Turnbull becomes entangled in one of the greatest corporate disasters in Australian history, the collapse of insurance company HIH. He assures us there is nothing to see here, either. Once again, you’ll end up rather better informed if you go to Manning’s biography.

His public profile increases enormously through his role in the Australian Republican Movement. The chapter on this topic is probably the most passionless of the book. It’s true he’s at the disadvantage of having written books on this subject before. But reading it now, it’s hard to imagine he ever cared enough to put in all those hours and hand over the $5 million he claims he paid to keep ARM going, but a lot of water has passed under the bridge since the defeat of the referendum in 1999. By the time he became prime minister, he couldn’t have made his lack of interest in pursuing the matter more apparent short of knighting Prince Philip. His predecessor already had that covered.

In 2004 he enters parliament via a good old-fashioned branch stack. He’s barely in the door before handing out advice on how to reform the tax system, which upsets the treasurer, Peter Costello. Still, John Howard soon promotes him to ministerial office, and, naturally, he is responsible for “one of the most enduring reforms of the Howard government,” the Water Act. Entering opposition late in 2007, he has to endure Brendan Nelson as leader, though apparently he has absolutely nothing to do with his fall. Nothing to see here.

Then, just four years after entering parliament, he becomes leader of the opposition. Good job. Malcolm tells us that, unlike Tony Abbott, he’s a “builder not a wrecker,” but he nonetheless opposes the Rudd Labor government’s second and larger fiscal stimulus during the global financial crisis because it wasn’t needed. China would have fixed everything anyway. In fact, he concedes almost nothing to the Labor government’s efforts to deal with the GFC. Malcolm always knows best, even in the worst economic crisis for eighty years, when plenty of minds at least as good as his own hadn’t a clue what was going to happen next.

He is deceived by weird and ill Treasury official Godwin Grech, who convinces him with a fake email that he has the dirt on Rudd. Turnbull is ashamed of himself — not, apparently, for accepting leaks from a senior Treasury official, but for allowing himself to be deceived and making that the basis of corruption accusations against Rudd. Turnbull loses the leadership in the midst of a party bust-up over the government’s proposal for a carbon pollution reduction scheme, which Turnbull wishes to support. He is betrayed by colleagues he trusts, and not for the last time. He goes into a deep depression in which he has suicidal thoughts and takes antidepressants. It is the most obviously honest section of the book. “I feel at present like a complete and utter failure,” he writes in his diary.

He decides to leave politics and then decides to stay. When the Abbott government is elected in 2013, he is given the communications portfolio with responsibility for the National Broadband Network, which keeps him busy. He doesn’t put a foot wrong, and the result is an NBN that is one of the best in the world. Nothing to see here, except “the largest single piece of infrastructure in Australia’s history.” Labor’s “smouldering trainwreck” is now “a success story.” Well done, Malcolm.

For Turnbull, there’s really no policy issue that won’t be resolved by turning his gigantic intellect to it — guided by a few corporate mates and old Sydney connections and the occasional academic researcher or clever staffer — and then applying a technical fix of some kind. So, cutting business tax is really just common sense because it will bring in investment and produce “jobs and growth.” There’s no need to ask whether it’s fair or even whether it leads to more investment or jobs, because Malcolm tells us it’s all good. On the other hand, he won’t touch negative gearing because it won’t help housing affordability as police and teachers own investment properties and the problem is really one of supply.

Tony Abbott and Peta Credlin make a hash of running the country. Abbott is “crazy” and “a threat to the nation and its security.” Scott Morrison is duplicitous and plotting, Peter Dutton extreme and plodding. Turnbull takes advantage of the gathering chaos and the well-founded fear that Abbott was leading the Coalition to defeat to move against his leadership. He wins the prime ministership, but Abbott, despite public undertakings of forbearance, undermines him from the very earliest days until Turnbull’s eventual fall. Still, the nimble Turnbull cleverly reforms the Senate voting system and engineers a double dissolution election for mid 2016. As ever, everyone including the media is left floundering and Malcolm is the smartest person in the room, the smartest person on every page.

But then things start to go wrong. Malcolm almost loses that election. It’s not his fault, however; it is Labor’s big lie that the government wanted to privatise Medicare. While recognising that his party has tended to unreliability on Medicare at times, including with Abbott and Joe Hockey’s 2014 budget proposal for a co-payment, not once does he pause to ask if he might have had anything to do with why the “lie” works. Could it be because Malcolm looks, sounds and acts like just the kind of guy who would try to privatise Medicare? Like a grammar school sook complaining of the beastly behaviour of the other boys on the rugby pitch, he makes a sulky, angry and graceless speech on election night that provides the country with a valuable insight into why so many people who have had to work with Turnbull rather dislike him.

Anyway, in the end it’s all okay because Australia by this time has entered a truly golden age of enlightened leadership: economically rational, socially progressive, firm, just and sane in its international dealings even when they involve tyrants like Donald Trump and Xi Jinping. Luckily, nimble Malcolm solves the problem of how to deal with the marriage equality issue. Opposed by both hardliners in his own party and a Labor opposition intent on using the issue for political gain, Malcolm finds a way through — the smart technocrat is triumphant again. He claims same-sex marriage as one of his government’s greatest achievements. For good measure, he denigrates the Yes campaigners; let’s not share any of the credit for reform, which is such a rare commodity these days. This chapter, along with his embarrassing special pleading about why he rejected the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, provides an especially vivid illustration of Turnbull’s chutzpah, opportunism and elitist understanding of politics. Cosimo de’ Medici would have understood it all too well.

A Bigger Picture leads us on a lengthy excursion through international meetings, policy triumphs and media conspiracies. Turnbull is proud of achievements, such as the foreign interference laws, energy infrastructure including Snowy 2.0, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (minus the United States). He defends Gonski 2.0 as good policy, but clearly also enjoys the politics of flaunting his old Sydney Grammar School chum in the faces of the Labor Party and teachers’ unions. With this Renaissance prince, Machiavelli’s Cesare Borgia is usually not trailing too far behind Cosimo de’ Medici.

Turnbull thinks he would have won the 2019 election if not for the blow-up of August 2018 triggered by legislation for a National Energy Guarantee. Indeed, he thinks that was why his enemies were determined to be rid of him. They were quite prepared to destroy the government in preference to having him continue as an enlightened and liberal prime minister.

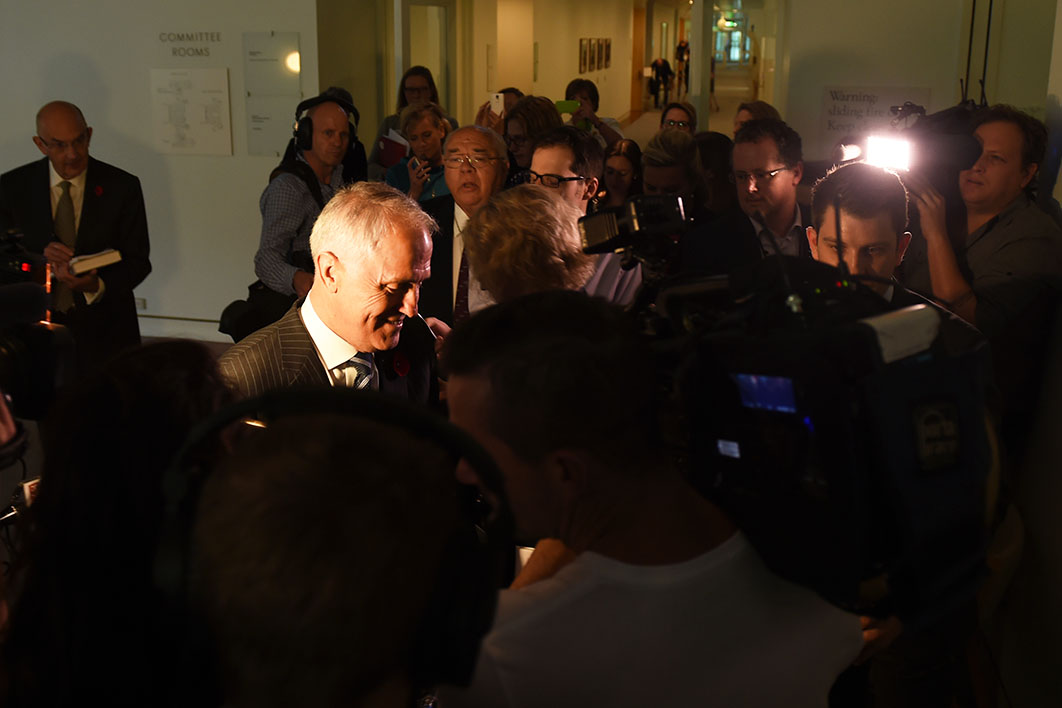

The last part of the book tells the tale of the demise of his leadership. Here, we are treated to the melodrama of Tony Abbott’s vengefulness, Peter Dutton’s mad ambition, Mathias Cormann’s cowardice and treachery, and the quiet duplicity of Scott Morrison — all of it oiled by the remorseless hostility of the Murdoch media and right-wing shock jocks. The right of his own party are “terrorists” determined to blow up the government. Others become persuaded that the only way forward is to give in to the “terrorists.”

I sometimes found this a distasteful book — not as distasteful as, say, The Latham Diaries (2005), but there are enough similarities to notice. Its combination of special pleading, broken confidences and bitter scorn will now become part and parcel of Turnbull’s reputation, and will confirm and harden the opinions of detractors. On the other hand, he is being naive if he imagines that a book so obviously self-serving will be taken at face value by the future political historians whom this historically literate man clearly has in view.

Nor will it alleviate the sense of disappointment that many, quite rightly, feel about Turnbull’s prime ministership. His prime ministership was not without its achievements, but Turnbull never really explains why someone who prides himself on being his own man allowed himself to become a hostage to the right of his own party, and to his Coalition partner, as readily as he did. Perhaps it was just vaulting ambition; once he had the prize in hand, and having been deprived of the leadership before, his main aim was to keep it.

Giving way to the right and the Nationals on issues such as same-sex marriage and climate change might have seemed a reasonable price to pay. But it was a strange course for a man who prides himself on being a canny deal-maker and, before the 2016 election at least, was holding all of the best cards. I don’t think it’s quite true to blame sheer opportunism, because I take seriously Turnbull’s claim that he is a constructive politician for whom power needs a purpose. My best guess is that Turnbull’s famously high estimation of his own intelligence and ability resulted in his overestimating his capacity to manoeuvre around those he regarded as lesser men and women — which was pretty much everyone else.

Turnbull certainly didn’t see coming the problems caused by his near loss in the 2016 election. It crippled his political standing and made his government vulnerable to internal revolt on the floor of parliament. But it would be psychologically impossible for Turnbull to admit that it was Bill Shorten, whom he regards with something of a grand duke’s condescension towards a rag-and-bone man, rather than Abbott, Dutton, Morrison or Cormann, who did the most to bring him undone. Nor could he have anticipated the difficulties in parliament caused by all those section 44 ineligibility cases.

Turnbull is unusual among Australian politicians in being willing to talk publicly of love, and it is clear that there is plenty of it in his own marriage and family life. But I suspect that, despite a bluster that many see as arrogance, he carries a lot more pain from his childhood than he is willing or able to disclose. I gained no sense from this book that religious belief plays a major role in his life, although he has converted to the Catholic faith of his wife’s family, and it might also mean more than he is willing to hint at here. There is certainly driving ambition, backed by the energy, bravado and intellect to achieve things most would find impossible.

Yet it has also been a career marked by big failures in things that have clearly mattered to him. As the history of Australia’s past fifty years is written, Turnbull will feature as a phenomenon more than as a politician or prime minister. In that respect, he will likely acquire a different kind of historical reputation from that of one of his few rivals as a larger-than-life public figure, Bob Hawke. The relatively modest nature of Turnbull’s achievements as prime minister will almost certainly ensure that he is not regarded as anywhere near as significant as Hawke. As with The Hawke Memoirs (1994), however, it seems a pity that this supremely gifted man was unable to produce a more generous and gracious account of an accomplished public life. But in Turnbull’s case, perhaps that is more a mark of what our politics has become than of his own character. •