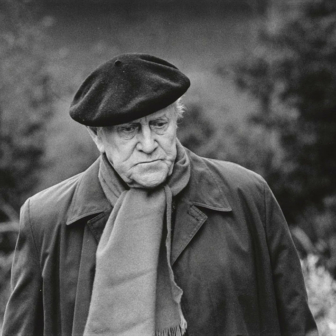

Harold Evans, who died in New York on 23 September 2020 aged ninety-two, was the most esteemed British newspaper editor of the later twentieth century. Justly so, given his rare portfolio of journalistic skills, girded by an omnivorous curiosity and an unflagging brio, a devotion to truth and a mettle in its pursuit. An apostle of the ideal of a newspaper as much as its practice, his books on press freedom, history, photography and tradecraft (the latter in five volumes) further attest to a core passion forged as a child of the “self-consciously respectable working class” around industrial Manchester in the 1930s.

During his golden years as editor of the Northern Echo (1961–66) and Sunday Times (1967–81), this rare blend of qualities propelled a chain of power-shaking scoops on many topics: from air pollution and cervical smear tests, through corporate tax avoidance and espionage cover-ups, to the blighting foetal deformities caused by an unsafe pregnancy treatment produced by the multinational Distillers company. Such hard-won breaches in the ramparts of official and corporate secrecy helped change laws and lives.

These two decades of editorial clout, fortuitously aligned with the liberalising arc of the 1960s and 70s, were the pinnacle in a working life of astounding longevity. Their foremost legacy is a perpetual glow around the very name of Harold Evans. Understandably so, for by turning both the Sunday Times’s “investigative journalism” and its “Insight” team into kinetic brands — then, at their climax, invoking editorial independence to resist Rupert Murdoch’s effort to sack him — he made himself one too.

The overlaid memory of that joust, as of Insight’s prosecutory storylines and courtroom skirmishes, would seal Evans’s reputation, and be reflected in many awards from his peers, from the worthy (two press institutes’ gold medals for lifetime achievement) to the cringy: an ever-trumpeted 2002 choice by a self-chosen handful of readers of the British Journalism Review and Press Gazette as “greatest newspaper editor of all time,” above twenty other nominees, all British and male, many distant and long unsung.

In the latter case, Evans’s tour de force acceptance essay (“My first thought was to check out the obituary page of The Times for reassurance”) paid those forerunners rich tribute, claimed a retroactive vote of his own, drew precepts from a tour of his greatest hits — and thus, in overall effect, flattered the wisdom of the exercise and its verdict. At seventy-four, Harry’s showmanship and genius for self-promotion, as much as his sheer panache in making words sing, were undimmed.

Decades earlier at the Sunday Times, a thriving paper known for “exposure reporting” long before Evans’s arrival, many had shared in the credit for its next-generation coups. Its burgeoning Insight squad, with Phillip Knightley, Bruce Page and Murray Sayle among the paper’s self-styled “Australian mafia,” continued to deliver the goods, far-sighted editor-in-chief Denis Hamilton the guidance, munificent proprietor Roy (Lord) Thomson the funds. The unstinting Evans, a wizard of publicity to match his editorial flair, was the catalyst. “Harold could be wild and impulsive, but he had the sort of crusading energy a Sunday editor requires,” Hamilton would say of his appointee, this much-recycled utterance invariably losing a qualifier: that Harold had “need always for a stronger figure behind him to see that his talents were not wrecked by his misjudgements.”

A midlife switch was to freeze Evans’s newspaper romance in aspic, and his early fame with it. In plain terms, a vain year-long shutdown of Times Newspapers Ltd from November 1978, sparked by printing unions’ staff demands and resistance to new technology, led to the company’s papers (including the daily Times) being auctioned. From a scrum of financial and political intrigue, Rupert Murdoch’s News International emerged in March 1981 holding the murky ball (“the challenge of my life,” said the tycoon, describing Evans as “one of the world’s great editors”).

Evans was persuaded to become editor of the Times, across a short bridge at the papers’ joint works at Thomson House on Gray’s Inn Road. But a fractious year later he was asked by Murdoch to resign, which he did after holding out for a week (itself a media sensation). Evans’s eventual formula was that he resigned “over policy differences relating to editorial independence.” His embittered memoir of the saga (Good Times, Bad Times) complete, he relocated to New York in 1984 with his second wife, zippy magazine editor Tina Brown, working there for Atlantic Monthly Press, editing US News & World Report and launching Condé Nast Traveler. Then, from 1990, he was publisher at Random House, where Joe Klein’s (initially “Anonymous’s”) Primary Colors was among his successes. Propulsive coupledom, reaching its zenith in the mid 1990s, buoyed his profile, as would his steadfast bashing of Murdoch (not least during the Leveson press inquiry of 2011–12) and of resurgent threats to the type of journalism he cherished.

This disjunction in Harry’s career — the ultimate British newspaperman turned transatlantic celebrity publisher — would always make it hard to see the whole. More so, as the surface contrast between its two halves was acute. Where the fitful second was laced with high-end networking and lucrative dealmaking, the first had a perfect narrative arc whose climactic duel simulated a mighty clash of values. The fact that martyr and villain stuck fast to their allotted roles (or could easily be portrayed as such) kept the storyline ever exhumable. On occasion their paths would cross, as when Murdoch’s own manuscript briefly landed on Evans’s desk. “The wheel of fortune makes me your publisher as you used to be mine,” wrote Harry, leading Rupert to call the whole thing off.

In that first half, the dramatic symmetry of Evans’s long rise and slow-motion fall also fitted the culturally potent image of the valiant journalist or editor. His Panglossian autobiography My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times, published in 2009, evokes the “newspaper films” of his childhood: “I identified with the small-town editor standing up to crooks, and tough reporters winning the story and the girl, and the foreign correspondent outwitting enemy agents.” That art’s blessing was a life in its image conferred on Evans a halo, dutifully polished in Britain’s media circles whenever his name came up, to which the details of his American experience (including citizenship, in 1993) would add not a speck.

As in the movies, uneven reality — in this case Evans’s editorial virtuosity, the feats (ever more roseate) of those Northern Echo and Sunday Times years, and the events of 1981–82 — was tidied into a seamless fable. His exit from London allowed it room to grow; fond tales of the press’s glory days gave it regular watering. A trade entering the digitised rapids could do with a hero to muffle its fears, and Evans, epitome of the age now under siege, was in a class of his own.

The campaigner

In a longer view, fate and chance, as well as exceptional will and ability, won Evans that esteem. Harry Evans’s steep ascent from modest origins in Patricroft, a district of Eccles — an “L.S. Lowry landscape of bent stick figures scurrying past sooty monuments of the industrial revolution,” in his words — was testing all the way. Equally, his early years were a good foundation: deeply loved as the eldest of four brothers, the family edging beyond poverty and upwards, remarkable parents who “[took] it for granted their boys would climb Everest.”

My Paper Chase’s portrait of his parents — father’s “phenomenal numeracy” and comedic gift (“We were part of the performance and his performance, like good theatre, always seemed fresh”), mother’s “ambitions for a better life,” which led from factory floor to her turning the terraced house’s front room into a grocer’s shop — signal that no child had a better start. Pride in his parents, whose evocative 1924 wedding-day photo is a highlight of the book, joined that in the leap from his mid-Wales grandfather, who left school at nine in 1863 for a labouring life, to his editorship of the Times. Yet Harry was phenomenal in his own right: such was his preternatural energy, it is tempting to imagine almost every obstacle in the route from Patricroft’s Liverpool Road via Gray’s Inn Road to Broadway giving up the ghost at the first encounter. Harry would never stop earning his charmed life.

Here he is as captain of St Mary’s school in Manchester in 1943, for example, where “[the] English teachers nominated a handful of candidates” for a planned magazine “and I was utterly shameless in campaigning to win the editorship,” or applying for his first newspaper job a year later and redrafting his headmaster’s testimonial (excising “too impetuous at present,” inserting “I wish him the glittering success he so deserves.”) Already, the ballast of Harry’s ultra-competitive spirit was a fervent attachment to the idea of newspaper journalism as his life’s purpose.

That sense of vocation had been seeded, he would often recall, by a holiday encounter with “weary and haggard” British soldiers in coastal north Wales in mid 1940. The mood of these survivors of the Dunkirk evacuation, sent across the country to recuperate, so contrasted with uplifting press reports of strong morale that the nearly twelve-year-old Harry — trailing his “compulsively gregarious” Welsh father, a train driver, who strode over from the beach to talk to the men — was bewildered. “Only two years later, when my ambitions to be a newspaper reporter flowered, did I understand that Dad was doing what a good reporter would do. Asking questions. Listening.”

This “epiphany on Rhyl beach,” the “first vague stirring of doubt about my untutored trust in newspapers,” also crystallised Harry’s eagerness to “involve myself in their mysteries.” Arrival at the Ashton-under-Lyne Weekly Reporter in 1944 would yield graphic social history, also in My Paper Chase, in the language of rapture: the huge Linotype “iron monsters” operating with the “autocratic urgency of hot metal marinated by printer’s ink,” men “crouched in communion” before them, an office “piled high with papers, telephone directories, pots of glue, spikes and a full-size glass kiosk with a chair and a candlestick telephone inside.”

Harry was never one to under-egg the pudding. Completing a portrait that mirrors, doubtless with its own fictive touches, the ennui of Michael Frayn’s evergreen “Fleet Street novel,” itself published in 1967 but set a decade earlier, are a “ginger-haired middle-aged reporter with a pipe clenched in his teeth” and “another wizened walnut of a man hunched over a desk [at] a window overlooking the market square,” working with “ancient typewriters on even more ancient desks that were sloped for writing by hand.” .

Two years’ solid experience at this century-old local paper with its thirteen daily editions was followed by two more of national service, where Evans created a newspaper for fellow Royal Air Force conscripts. That opened a channel to university study at historic Durham, a north-east cathedral city, where he edited the student magazine and went on to complete a masters in American foreign policy. Back home as assistant editor at the Manchester Evening Times from 1952, and soon married to Enid Parker, a biology graduate and now schoolteacher, he was awarded a Harkness fellowship in 1956-57 to study in the United States, where the young couple’s extensive travels provided a close-up view of the civil-rights tumult.

Harry, still under thirty, going places for sixteen years, was now a coming man. The Guardian, sister paper of the Evening Times, was mooted as his next berth, a move stymied by the top brass’s opposition to internal staff transfers. Instead, in 1961 he became editor of the Northern Echo, a historically Liberal daily based in Darlington, a market town and railway hub twenty miles south of Durham. A prominent regional paper, its main rival the Leeds-based Yorkshire Post, the Echo had been edited through the 1870s by W.T. Stead, daredevil inventor of popular journalism in Britain, for whom the job was “a glorious opportunity of attacking the devil.”

Evans soon made a splash. His team spotlighted the malodorous, lung-busting pall issuing from Middlesbrough’s chemical plants and the ear-drilling roar of mega-lorries through Echo readers’ towns and villages. A brief Sunday Times item on British Columbia’s cervical cytology program led to his reporter Kenneth Hooper’s landmark 1963 series, “Saving Mothers from Cancer,” its full-page opener, “The Tragedy of Thousands Who Need Not Die,” kindling the armoury of pressure that a year later saw cervical smear tests available in principle to every woman in Britain.

So often, that knack for noticing, and being nagged by, an issue already in circulation would produce a big story — one, moreover, that came to be associated chiefly with Harry himself, in part by his insistent coverage, in part by the way (expansively selective, it might be said) he orchestrated the plaudits.

There had, for example, been four books, a joint press effort and a parliamentary debate airing claims of a miscarriage of justice over Timothy Evans, a pliant Welshman hanged in 1950 for killing his infant daughter in a Notting Hill flat (and charged too, though not tried, for strangling his wife, Beryl). When a local Liberal manufacturer wrote to the paper exhorting a new push to exonerate a man whose bad breaks in life included having a mass murderer as a downstairs neighbour, the Echo’s newsroom initially featured the letter as a slow day’s stopgap. But Harry’s promotional nous swiftly made his namesake the Echo’s new lead cause, with “Man On Our Conscience” following “The Lorry Menace,” “The Smell,” and more.

A senior judge’s review of the case denied full vindication to Timothy Evans, even perversely deducing that he was innocent over the baby but had murdered Beryl. Yet the momentum for redress did secure the executed man a pardon in 1966, and three years later Harold Wilson’s Labour government, having already suspended the death penalty, abolished it. That Harry reworked the saga with himself as the linchpin might have led even W.T. Stead’s glowering portrait on the Northern Echo’s wall to crack a smile.

The moment

The high road to London was opening. Evans was already known there, and not just by Fleet Street’s talent spotters. In 1962, he had joined the presenters’ roster on What the Papers Say, a pacy late-night weekly round-up on Granada, the groundbreaking Manchester-based arm of Independent Television. The program displayed choice extracts from the week’s headlines, reports and columns, each given a pitch-perfect comedic slant by offscreen voice actors, threaded by pithy scripts from a single, straight-to-camera journalist. With his dapper good looks and dry Mancunian tones, Harry was a clever hire among a rolling mix of seniors and thrusters.

Such opportunities arose in a definite social moment, from 1957 to 1963, when the abrasions of rapid social change were most vividly felt in industrial northern England. In these years, “the north,” that country of the mind — far from coterminous with the actual region, as with Fleet Street and the newspaper industry — was catapulted to an unexpectedly modish berth in the national imaginary.

The northern vogue had been heralded in its ur-text, Richard Hoggart’s celebratory lament The Uses of Literacy, published in 1957. It spread via a tranche of emotionally truthful novels, films and plays, as well as Granada’s Coronation Street serial, which dramatised the theme of generational tension (while offering London a voyage of discovery to an outlying planet). Just as quickly, against a backdrop of exultant ridicule from the concurrent, largely Oxbridge, satire boom, it sank into imitation and canny nostalgia.

Above all, the Beatles’ early success brought the phase to a suitably ambiguous close. The group’s electrifying jolt added joy, wit and optimism to the north’s new–old connotations (authenticity, poverty, melancholy, communalism, boorish masculinity, dreams of escape often thwarted). In crowning the region’s enhanced appeal — and hauling its centre of gravity west to the Atlantic port city of Liverpool — the Beatles also made its previous terms look antiquated.

The moment’s principal benefit was to Harry’s cohort: northern working-class boys born just too late for a wartime call-up, adolescents in the 1940–51 Churchill–Attlee era, nourished by family, public library and welfarism, their sound basic education providing a ladder to grammar school, perhaps university, two years of national service fuelling impatient ambition. Together, these influences formed an apprenticeship to the middle class, even to the part of creator or activator.

Evans was among the older of the group, like Stan Barstow (A Kind of Loving), Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall (Billy Liar) and Tony Richardson (the middle-class director who adapted Shelagh Delaney’s play A Taste of Honey) — all bar the precocious Delaney born in 1928–29. Its members carried the uncharted ambiguities as well as the enticements of their newly mobile class and regional status. Some of those who, unlike Billy Liar, did jump on the train south became luminaries of British public life by making an asset of their northernness, while others did so by shedding local attachments, and accents, in order to fit in. Harry’s was a third way: when he invoked his northern background to New York audiences, most often to deride England’s taints of class, this would serve as a measure of how far he had come.

The mentor

Within the newspaper world, Evans’s performance at the Northern Echo and on What the Papers Say turned into an audition for the London stage. The big break, in 1966, came as an invitation from Sunday Times editor Denis Hamilton to work as his assistant. A year later Evans landed the editorship when the Thomson organisation, owners of the paper, purchased the Times and Hamilton became editor-in-chief of both. The venerable pair (the daily being founded in 1795, the weekly in 1822) were thus brought under the same owner for the first time, a factor — often masked by their similar titles — that took on greater significance as Times Newspapers Ltd, or TNL, entered crisis in the late 1970s.

Now Evans was again walking in Stead’s shoes, the earlier Northern Echo editor having become deputy to John Morley at the Pall Mall Gazette in 1880 then, three years later, succeeding him in the chair. Stead had quickly netted an array of scoops, culminating in an 1885 exposé of the business of child sexual exploitation by London toffs under the authorities’ blind eye. Procuring a thirteen-year-old girl as evidence of the traffic, Stead was sent to jail for three months via a parliamentary bill rushed into law in response to his own story.

The Stead–Evans parallels are resounding. Many colleagues would come to speak of Evans in terms that eerily chimed with those of Stead’s assistant at the Pall Mall Gazette, Alfred Milner: “I cannot recall one who was anything like his equal in vitality… I don’t suppose any editor was ever so beloved by his staff… It was such fun to work with him. The tremendous ‘drive,’ the endless surprises, the red-hot pace at which everything was carried on… His sympathy, his generosity, his kindliness were lavished on all who came within his reach.”

Also akin to Harry’s finest were Stead’s walloping, if in his case prurient, taste in headlines (“The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon”) and eclectic investigative unit — veteran feminist reformer Josephine Butler, the Salvation Army’s Bramwell Booth and brothel-keeper turned activist Rebecca Jarrett. And if Evans wasn’t locked up for his principles, he raised the prospect, with a touch of melodrama, in replying to Phillip Knightley’s tip that rivals, disregarding legal qualms, were about to usurp him over the thalidomide story: “I’m tempted to publish anyway. I’ll go to jail. That’s what I’ll do. I’ll go to jail. Bloody hell, it’d be worth it!”

The audacity of Stead and Evans, each a decade younger than their patrons, led them to eclipse the latter in what passes for journalism’s collective memory. Ineluctable or not, that is a disservice to Morley, a principled, scholarly Liberal from Blackburn, north of Manchester, who eventually left journalism for politics; and to Hamilton, a Middlesbrough reporter in his teens who rose by his mid twenties to acting brigadier in war and returned to steer a newspaper group before himself editing the Sunday Times. Equally, it is a disservice to history, for it hoists the whirlwind talents of the more glamorous pair above the singular weave (of inheritance, relationship, contingency and action) in which these talents were enmeshed.

Hamilton, for his part, as well as recruiting Evans laid the groundwork of the latter’s good times in London. He had spent a decade running the Kemsley stable, a mix of national and provincial papers, when in 1958 he made use of his war service under Montgomery to clinch serialisation of the field-marshal’s memoirs for the Sunday Times, a coup that widened a circulation lead over its Observer rival opened by the 1956 Suez crisis. Hamilton became editor in 1961, two years after Thomson’s buyout of Kemsley, and in his six years at the helm took the paper’s sales from under a million in 1959 to a record 1.5 million.

If by this time Denis Hamilton was a consummate establishment insider, eventually to be knighted, his distinction was to be an innovator with foresight. From the editorial plan, graduate training scheme and “big read” of the Kemsley era to the colour magazine, Insight and business section of the Thomson one, Hamilton made the newspaper a weekly event, outpacing the rival Observer and new Sunday Telegraph, while keeping the horizon in view. “More and more I was convinced the Sunday Times should analyse and amplify the news and what lay behind it [in order] to do what television didn’t do,” he reflected, thus drawing “potential readers with greater leisure and affluence.” Hamilton’s strategy, from the big read (“our secret weapon”) to “Atticus,” vignettes of upper-class life by Kemsley’s influential foreign manager Ian Fleming, anticipated the blockbuster weekend newspapers of the 1980s.

The original Insight team of Ron Hall, Clive Irving and Jeremy Wallington was enlisted by Hamilton in 1962 after the youthful trio’s experimental, admired news-in-depth weekly Topic had folded after a few months. At the Sunday Times, their exposure of London’s rental housing underworld (symbolised by the figure of Peter Rachman), a fake Beaujolais scam, and the Profumo affair’s tentacles added punch to the paper. Working on the scandal that brought down Britain’s defence secretary, said Irving, “would tip us into the future of long-form, narrative reporting.”

The nous that had led Hamilton to these bright sparks informed his choice of a replacement when Kemsley’s purchase of the Times forced a company reshuffle. Roy Thomson, self-made son of a Canadian barber, now domiciled in his ancestors’ Scotland, strictly upheld editorial independence (“no person or group can buy or influence editorial support from any newspaper in the Thomson group” was his “creed”) but also took against Frank Giles, number three at the paper and the obvious choice. “Harold’s north country cheek matched Roy’s own,” recalled Hamilton. “In order to convince myself — and others — that Harold was the man, I asked him to set out his ideas of where, over the next few years, the Sunday Times should go. This paper, written over a weekend, was an impressive document that tipped the scales.”

To adapt an old phrase, those who talk of Harold Evans shouldn’t be silent about Denis Hamilton. The British Library’s former head of newspapers, Ed King, wrote of his memoirs: “I was struck time and again by Hamilton’s great capacities: for dealing with people successfully, for being able to take criticism, for delegating work and responsibilities, for learning, for sustained hard work, for seizing the moment, for his incorruptibility. Above all, he had the (constantly exercised) ability to reflect on gaps in the newspaper market, to think ahead, to plan a campaign of action for the future. For many years, Fleet Street was a sufficiently large canvas for his abilities to show at their best.”

For Hamilton, hiring Evans was a conscious act of rejuvenation, one of many. Yet as with Morley vis-à-vis Stead, collaboration sharpened differences. Evans “proved himself an editor with immense flair,” Hamilton would reflect, but “had a great weakness for self-projection” and “was the world’s worst recruiter”; Harry, invited to read a poem at Denis’s funeral in 1988, called him “my mentor for some twenty years,” a note never repeated, even in My Paper Chase (whose 500 pages and ample bibliography, moreover, contained zero reference to his own Good Times, Bad Times). For all that, their partnership — and Roy Thomson’s fortune — helped deliver another decade of dominance for the Sunday Times, until in the late 1970s the paper’s share of Britain’s fracturing social contract brought the whole operation to an impasse.

The boy scout

“I’m handing you a Rolls Royce,” Denis told Harry as they descended to the composing room to see off the last edition of the Hamilton era at Gray’s Inn Road in January 1967. The weekly, sixty-four page (later seventy-two) ad-friendly package of features, serials, comment and foreign reportage, strong on graphics and photographs, had maintained a firm commercial lead. Harry soon made its reportorial language more direct and its presentation more appealing, its muckraking busier if increasingly distended.

Above all, the Sunday Times took on a distinct swagger, which tended to make it more envied than admired in press circles. That had a rationale, for the paper’s assets — market dominance, cash to burn, abundant staff, a hotshot editor-ringmaster touting his wares on TV chat and quiz shows — were hardly those of an underdog. And when Harry sued the satirical magazine Private Eye for needling him as “Dame” (he saw its feeble link to the actress Dame Edith Evans as an “imputation of effeminacy”), the crusader evinced a censorious instinct and odd sense of priorities.

Yet even taking account of the unlimited resources at his disposal, Evans’s exploits as editor were substantial. Several of the major Sunday Times investigations of the next decade entered journalistic folklore, in large part because they entailed positional or legal tussles with a state intent on the lid staying clamped. Among them were the backstory of Kim Philby, the suave British NKVD agent who infiltrated MI6 at the top level and in 1963 fled to Moscow; reporting of Northern Ireland’s conflict that filleted the official version of key episodes; publication of Labour cabinet minister Richard Crossman’s diaries, penetrating thick walls of confidentiality; and exposure of negligence and cover-up over the birth of thousands of disfigured babies (mainly between 1955 and 1962) whose expectant mothers had taken thalidomide for morning sickness.

In each case, a “state of knowledge” timeline was the basis of a detailed narrative, constantly updated, with plenty of personal dramas and cliffhanger moments. It might branch in all directions — Elaine Potter’s meticulous research into the pregnancy drug’s testing failures, and Marjorie Wallace’s tender interviews with stricken families, for example, counterpointed by reports and graphics on the issues at stake: press freedom, state secrecy, corporate powers, citizens’ rights. A book-length Insight-branded digest could soon follow, its sales (as of the Philby or Ulster potboilers) recouping much of the newspaper’s costs. Chance and design had made for a winning formula: albeit the hunt for more makeweight quarry, and there was plenty, exposed little beyond Insight’s style of portentous urgency.

At its best, the Sunday Times’s journalistic alchemy saw Evans’s sparkling life-force, quicksilver judgement and ire at restrictive laws — libel, contempt of court, official secrecy — kindle his smart newshounds’ ingenuity and grit. Evans was an “all-rounder, a brilliant technician, famously courageous,” recalled Godfrey Hodgson, Insight editor for four years. “He could grasp the point and scope of a story at speed. When Anthony Mascarenhas brought in his 1971 scoop on the repression in then East Bengal, which led to the birth of Bangladesh amid millions of refugees, a cholera epidemic and war, Evans swept away a pedestrian headline (written by myself) and replaced it with a single word, “Genocide,” in 72-point type.” Then, “after the first edition had gone on a Saturday night” his “seminars over a glass of scotch were models of instruction and motivation.”

Harry’s lessons went beyond the inner sanctum. On broadcast media and contributions to the weekly Listener or New Society, he was a lucid champion of bold journalism as pillar of a free society, and the more persuasive for his framing the case in moral and empirical, as opposed to doctrinal, terms. In the same spirit, his Northern Echo proselytising had been circumstantial rather than planned, he declared, “arising from frustrations and disquiet as we encountered instances of a vast carelessness in public life,” while at the Sunday Times, seeing London’s hidebound institutions at close range, he had come to detect “a chronic but unsuspected malaise in the functioning of British democracy.”

If such sentiments dovetailed with the social progressivism of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Evans was more inclined to finesse anti-establishment sentiment than inhale it. In the spirit of Stead’s “government by journalism,” he wanted to clean up the temple, not pull it down. This disposition marked his whole career: just as at Durham’s student debates, a natural Labourite and go-getter, he had recoiled from “the warriors of cold reason,” he was averse to the heavy radicalism of the 1960s and 70s, and — this time born just too early — rueful in missing that elusive thing, the sexual revolution.

For all his cogent justifications of dragon-slaying, Harry remained the boy scout he had in fact been: neither cynic, ideologue, nor even much of a political animal at all (an “apolitical liberal,” his buddy Robert Harris called him). Proximity to the exalted, with their titles and trappings, could beguile as ideas did not. “He sometimes seemed too keen to please the powerful,” the scrupulous Hodgson listed among his faults.

At root, this deferential streak was just another part of Evans’s all-embracing, all-consuming personality. The tendency might be overt, as when he held back Murray Sayle’s timely dissection of the Bloody Sunday massacre in 1972, or enfolded into investigative work’s grey zones, such as liaising with MI6-adjacent personnel during the Philby story to keep the intelligence agency in the loop and at bay. Harry was too bumptious for artifice anyway: in an office lie-detection experiment in 1979 with visiting celebrities he “failed to lie successfully” (as did Sunday Times reporter Isabel Hilton, who wrote a deadpan account of the episode).

That personality, always more consequential than any public views Evans might espouse, drove (and could also block) the paper. Insight’s investigations bore its imprint, from their often drawn-out gestation to the way their ambivalent endings were oversold as victories. Harry’s divided attention, and his intoxication with a process under his nominal control, could entail a loss of focus. The Philby story, for example, had to be rushed out when it was found that the Observer was splashing on the memoirs of Eleanor Philby, third wife of the “third man.” Similarly, the trigger for launching the thalidomide campaign in 1972 was that a trio of Daily Mail features on an afflicted family had got ahead of the Sunday Times’s long delayed coverage after Mail editor David English decided to brave legal constraints. Worse, the resolute father was now telling lead reporter Phillip Knightley that Murdoch’s News of the World had its own thalidomide series in the works.

Knightley, going to his editor with the information (and aware that “Rupert doesn’t give a damn about the Attorney-General”) found a panicky Evans “determined not to lose the story.” Looking back in his 1997 autobiography A Hack’s Progress, he cited the Sunday Times’s snail’s pace, as well as families’ distress over skewed compensation and media exposure, to argue that the whole thalidomide effort “was not the great success it was made out to be, and that the full story is as much about the failures of journalism as about its triumphs.”

Fleet Street’s competitiveness was central to investigative journalism in the period. So too, and also barely recognised, is the role of Denis Hamilton before and after Evans’s arrival at the Sunday Times. In his own account Hamilton found that the “emotional and highly strung” Evans needed “constant counsel and comfort — for instance, when we took on the law over the Thalidomide case (which was his idea) I controlled the whole campaign. No sentence appeared in the newspaper without my having seen it beforehand, and I ran the strategy, as I did the fight against the Cabinet Office over the Crossman Diaries. [In] the end we won the right to publish the diaries, though in the book which Harold Evans later commissioned to record the case my name did not appear, to my great interest. I didn’t object — I came to know, over the succeeding twelve years, Harold Evans’s strengths and weaknesses better than any man in Fleet Street.”

This blunt rectifying impulse is alone of its kind in Hamilton’s overview of his career, taped during cancer treatment by his historian son, Nigel, and published in 1989 as Editor-in-Chief: The Fleet Street Memoirs of Sir Denis Hamilton. The reams of exalted make-believe that two decades later would fill Evans’s own My Paper Chase, treating Hamilton (where present at all) as in effect a hapless extra in Harry’s biopic, were his posthumous reward. That aside, an Evans-centric prism impedes grasp of these Sunday Times years. They are far more complicated, and thus far more interesting, than chronic romanticism and veneration allow.

The lord of misrule

The Sunday Times’s illumination of shadowy worlds added to its own glare. But Harry, the editor as impresario, always had much more on his plate — as well as in his pockets, up his sleeves and under his hat. On the inside, life at the paper became more of a rollicking Range Rover ride across bumpy terrain.

Prue Leith, a freelance food writer, once entered Harry’s office as he faced the window, doing star-jumps. “As he shook out his arms and legs, he said, ‘Oh, I just have to get rid of some energy.’” Skiing was a new passion, he went on, and — anticipating reality TV by decades — he intended to commission a band of journos also in their forties to learn its joys. He did too, and a book (How We Learned to Ski) came out of it. All the while, he was completing the instructional Editing and Design: A Five Volume Manual of English, Typography and Layout (comprising Essential English for Journalists and Writers, Handling Newspaper Text, News Headlines: An Illustrated Guide, Pictures on a Page: Photojournalism, Graphics and Picture Editing, and Newspaper Design).

Harry “understood the craft of journalism better than any of us,” said his colleague Magnus Linklater, editor of the “Spectrum” pages, who also recalled daytime squash games at a Pall Mall club where he “would turn up late, clutching a sheaf of papers and gallop to the telephone. Then he’d scurry into the changing rooms, talking nineteen to the dozen. I can never remember him motionless. His walk was a half-run. He was exhausting to compete against… and liked beating me, partly because I was fourteen years younger.” Linklater, an urbane Scots Etonian, also spoke of Harry’s “combination of intellectual ferment with almost naiveté,” as when he would buttonhole the corridor “tea ladies” to ask if they found the paper’s stories offensive.

At Gray’s Inn Road he managed to be at once ubiquitous and elusive. “‘Where’s Harry?’ was the cry that went up most days on the editorial floor,” wrote features sub Elizabeth Grice, where the editor “was quite often a blur. A slight, mercurial figure, he moved so fast and with such will-o’-the-wisp unpredictability between the editorial floors and the print room that it was impossible to locate him with any certainty. Sightings were passed from reporter to reporter in the event that someone needed to know. He boasted that his door was always open but he was not always inside it.”

Harry’s relentlessness could irk colleagues, as when at the last moment he would needlessly sub-edit copy (or duplicate the paper’s chess notation on a miniature set to confirm its accuracy). It could also elicit awe, in terms again reminiscent of Milner on Stead: “He would go on debating, with the printers screaming for ‘copy,’ till he sometimes left himself less than half an hour to write or dictate a leading article; then he would dash it off at top-speed and embody in it, with astonishing facility, the whole gist and essence of the preceding discussion.”

Richard Dowden recalls a 10pm alert that a rival paper was reporting the collapse of DeLorean, a flagship sports car company in Northern Ireland. When Dowden got through to the owner, Harry, “dancing with agitation,” seized the phone, “scribbled some notes and threw them at me. ‘Clear the front page!’ he shouted. I couldn’t read Harry’s shorthand so he began to type at frenetic speed. He gave it to the compositor. In a matter of minutes Harry Evans had taken lightning shorthand, typed out the story, and relaid the front page, making the interview with [John] De Lorean most of it. He then went to the stone, where the hot type was set, and within minutes the presses were rolling again. He then began calling government ministers. The problem was that the story was wrong. But as a newspaperman Harry Evans had an unsurpassed brilliance.”

Dowden’s vignette is in fact from Evans’s Times coda, a month before his sacking by Murdoch, thus evidence that he hadn’t changed. Many colleagues’ fondness is similarly fringed with ambivalence. The Sunday Times’s literary editor Claire Tomalin compared working under Evans to “being at the court of Louis XIV. When he beamed his attention fully on any one of us, we were all, men and women, a little in love with him… Harry was loved, even if we sometimes swore at him when his attention was distracted or his favours divided.”

The sense of a quasi-monarchy under arbitrary rule persists, albeit infused with genuine warmth. Philip Norman, whose competition entry had earned him a place on staff, was touched by the editor’s balm: “With Harold Evans it was more than working for a newspaper, you felt personally that you worked for Harry. Editors tended to be sulking autocrats… but Harry was everywhere, running from the subs desk to the writers, perpetually in motion… He was the boy king, Henry V, and anybody would have done anything for him. He didn’t overlook anybody, we were all special.” For Godfrey Hodgson, the editor “was, in fact, loved by most of his staff, not an easy thing for a man with power over the careers and reputations of ferociously ambitious and competitive people.”

A recollection by Knightley hints at the ambiguities at play. “[Harold Evans] wore his editor’s skills so lightly. He was master of every branch of journalism. He could lay out a page, choose a photograph, dash off a leader, write a headline. The only thing he couldn’t do was say ‘No.’ So he gave a job to anyone who asked, which meant that the Sunday Times was wildly overmanned. It had so many curious staffing arrangements that I doubt anyone really knew how many journalists worked there. Or what they did. Evans never tried to bring order to the editorial department’s creative chaos. He simply encouraged journalists to get on with whatever appealed to them. Such freedom was unprecedented and I mourn its passing.”

Where some regarded his anti-method as wasteful and damaging, Harry saw only benefit, citing his promotion of Elaine Potter to work alongside Bruce Page: “She’d not had a great deal of experience in journalism, but she’d acquired an Oxford Ph.D., and, as important, squatter’s rights to a freelancer’s chair in the features department. Some of our most successful recruits were squatters; they were tested by the exigencies of sudden demands for labour and the best, like Elaine, survived with the complicity of editors until I could find a place on staff.”

Potter, commending Harry as “fierce in pursuit of wrongdoing,” and for his stress on “the importance of repetition, of staying with a story if you wanted to make a difference,” says — with much unspoken between the lines — he “surrounded himself with forceful journalists, all of whom wanted to be heard, none of whom would readily give way to the considerable editor of a great newspaper. Undaunted he would do battle with this fierce crew who spent even more time jousting with each other.”

Harry’s support, job-enhancing and moral, could inspire great loyalty. Marjorie Wallace, enlisted at a Highgate tennis club by a figure of “missionary zeal” whom she at first thought “slightly crazy” as he insisted on finding her a child-minder that very afternoon so she could start work, found him “a true crusader with fierce moral purpose who put his head above every parapet.” Well into her stint at the Sunday Times, she expected to lose her job after confessing to her editor that, under family pressures, her copy had long dried up, but instead was told with a smile: “Don’t worry. Every journalist has a fallow period.” Yet she also writes that Harry “could be capricious, frustrating and infuriating. When a promotion came up at the paper, he would offer at least five of us the job before leaving us to sort out who got it between ourselves. It created a highly competitive environment that had its ruthless side.”

Harry thrived as lord of this misrule, all of it kept afloat by the most innocently enlightened of press moguls, Roy Thomson, who had defined “the social mission of every great newspaper” as in part “to provide a home for a large number of salaried eccentrics.” But misfiring appointments and ballooning payrolls did cause strain between Evans and Hamilton. “In a couple of extreme cases I had contracts rescinded, which led to a showdown with [Evans] in which I said that recruitment above a certain salary had to have my permission,” the editor-in-chief recounted.

Such reproval cut no ice with Harry, whose derision for his paymasters was a career motif. He had paid big sums to get inside information on thalidomide and Paris’s DC-10 crash in 1974. His ill-starred year at the Times featured rapid turnover where incomers were better paid than those who left or were let go, both factors triggering staff resentment. Visiting the Northern Echo in 2000, having received an award at the nearby university, he was asked by its newish editor for a word of advice. Harry’s pithy reply, with its show-off expletive, was: “Don’t take any notice of the fucking beancounters.” No editor ever regarded a proprietor’s bounty with as much airy contempt.

The liberated zone

In the many-ringed circus that was the Sunday Times of the 1960s and 70s, the colour magazine — design pioneer, aesthetic blast, sales magnet, radical chic show — went its own way. It too would be embroiled by tensions over cash, authority and personnel during Harry’s time at the paper, its redoubt on Thomson House’s fourth floor becoming, he confided, a “source of enormous frustration.” The awkward dance that ensued between its autonomy and his search for control doesn’t fit easy accounts of his brilliant career, which means it gets no traction there.

Dreamed up in 1961 by Roy Thomson and the marketing department, brought to fruition in February 1962 by Hamilton, the then “section,” or informally “supplement” — the law barring magazine publishing on a Sunday — had withstood gigantic losses in its first year to become an editorial success and lucrative advertising funnel. Hamilton’s strategic confidence plus intrepid marketing had overcome that nervy start. Capping the turnaround was the team’s anniversary “Moscow picnic” in February 1963, when the chirpy Roy Thomson interviewed Khrushchev and offered to buy Pravda.

Under a coterie of independent, exacting spirits — notably artist-editor Mark Boxer and literary editor Francis Wyndham, art director Michael Rand and graphic designer David King — the magazine’s blend of big subjects, top names and bold visuals rivalled Insight in defining the Sunday Times to the public. And its renown was as great, imaginative openness to swirling Sixties currents making it part of the decade’s “revolt into style.” The newspaper’s id to Insight’s super-ego, it might be said.

The magazine was piloted in its first three years by Boxer, another astute Hamilton pick. (“I felt he had the necessary kind of iconoclastic attitude, a chap I’d have to restrain rather than ginger up.”) Mark “lived on the front edge of life,” said his successor Godfrey Smith, himself more a Falstaff, under whom the lotus years took wing, with their epic lunches and staff jaunts, one such, to Sarajevo for the feature “A Day in The Life Of,” spawning no copy at all because Michael Rand judged the photographs too weak to use.

Hamilton’s personal attachment to his baby (“perhaps the most successful innovation in postwar quality journalism,” he called it) was such that he had kept the magazine out of Evans’s hands, ostensibly to allow the new editor to focus on the main paper, though he later elaborated: “I confess that in my heart I was really worried stiff about [Evans’s] at times impulsive approach.” The magazine was granted years of latitude to resist intruders and replenish itself.

The fourth floor had the seductive thrill of a liberated zone. For those outside, it was a problem child: “frivolous, self-absorbed, anarchic, [prone to] self-indulgence and money-wasting” were the vibes picked up by a young James Fox as he went to work alongside Wyndham and “hard-working, hard-typing” fashion editor Meriel McCooey, their office the magazine’s “subversive cultural centre and magnet for visitors.” That the latter included depraved gangsters with contrarian appeal, from the Kray twins to the predatory far-left guru Gerry Healy, whose acolytes included the Redgrave theatrical family, had a taste of self-styled vanguards paying court to each other.

Evans recoiled more from the magazine’s distinct angle on news stories, as for example when the texts accompanying Don McCullin’s photographs of Nigeria’s civil war had greater sympathy for the Biafran side than the paper’s reporting. He “would want to pull out articles — usually on grounds of taste — when they were already on the cylinder, at the cost of thousands of pounds,” wrote Fox. A chance to bridle the magazine came in 1972 when Godfrey Smith’s move to associate editor at the paper freed Evans to deploy the versatile Magnus Linklater behind enemy lines. (“Go in and sort that lot out,” was the brief.)

The new broom soon warranted the choice by unearthing £70,000 worth in paid-for commissions lying idle. But the magazine’s uncommon ethos and “brilliant people” inveigled Linklater, whose expensive advance to Patagonia-bound Bruce Chatwin convinced Evans that the magazine was “self-indulgent, mired in triviality, out of touch.” Linklater rode accusations of “going native” for two years before Harry abruptly replaced him with the breezy populariser Hunter Davies, a pal from Durham and Manchester days, whose stab at curbing the renegade took a year to fail. The struggle for control, in Fox’s words, was “eventually settled by Murdoch.”

Linklater’s farewell party, within hours of returning from lunch to be told of his transfer to assistant news editor (no one was ever pushed out of the old Sunday Times), had combined mutiny and wake. Harry dared to come, Meriel McCooey, his very antithesis, yelling at his ashen face: “You! I mean you! William fucking Randolph Hearst! Do you know what you’ve done?” In the silence, Michael Rand’s remark to art assistant Roger Law rippled across the room and sank deep: “The party’s over, boys.”

The twilight

Fleet Street’s teeming warrens, marinated in alcohol and trade gossip, rarely spilled their own guild secrets further than Private Eye’s “Street of Shame” column. Newspapers’ domestic life was off limits, as the playwright Arnold Wesker found in 1971 when Evans gave him permission to “wander freely through the offices of the Sunday Times to gather material,” only to find that his dramatic theme — journalists’ corrosive desire to cut everyone down to their size — made his work unwelcome. The Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Wesker’s 1972 play, The Journalists, based on his eight weeks at the paper, was scuttled when the actors refused to perform it. Between artistic defects and the tug of Healy’s cult, the Workers’ Revolutionary Party, there was a lot of blame to go round.

A whiff of the power games and raw emotions at the Sunday Times did filter into intellectual journalism’s periodic overviews of the news machine. Two liberal observers were notably alert to the paper’s internal fissures and shrewd about Evans’s capacity to handle them. Anthony Sampson, in the third, 1972, edition of his Anatomy of Britain, sketched a publication “driven on a loose rein” by Evans, who is “pulled in several directions” by journalists “competing fiercely with each other for exposures and scoops.” The Sunday Times “likes to give something for everyone: it has left-wing politics and right-wing politics, exposures and court circulars, and it has romped ahead on this formula. But its corporate character, partly as a result, is uncertain.”

In a similar vein, an anonymous New Statesman profile in 1975, bearing the stamp of the magazine’s editor Anthony Howard, used W.T. Stead’s demise aboard the Titanic to propose that Evans’s “unwieldy vessel” needed its pilot “to set a course”:

“The major decisions he takes; the more mundane ones he puts off. The result is a paper where no one quite knows what is happening, where the wrong men are left in the wrong jobs, and an almost accidental ‘policy’ of divide-and-rule causes some unhappiness and irritation. The man who did not like taking unpleasant decisions on the Northern Echo still fears unpopularity. If Harold Evans realised how much actual authority, and professional respect, as well as affection, he commands among his staff, he might (as one of his executives put it) ‘calm down and organise a better newspaper.’ But his combination of talents is also his weakness: intelligent, charming, a brilliant journalist, he still has to prove it, still has to be seen to be good.”

These judicious appraisals of the upper deck skirted the iceberg below: the unremitting war between management and print unions, with journalists caught in the middle. Newspaper production was at the mercy of “chapels,” or union branches, each led by a “father” who acted as a spiky guardian of shop floor customs and his extended family’s interests. There were fifty-six chapels at Thomson House alone. A stoppage by one, on the flimsiest of grounds, would halt the paper. In the mid 1970s, the Sunday Times was losing millions of copies a year. (“Industrial anarchy,” Harry called it.) “The management lived in fear of strikes, and we were all obliged never to offend a printer,” wrote Claire Tomalin in A Life of My Own.

The Sunday Times’s revenues were badly hit, its ambition to grow sales to two million long busted, though it stayed profitable. The Times, less secure in the tough weekday market, was in dire trouble, draining each year £2 million from Thomson’s coffers, fortunately swelled by his agile investments in television, travel and North Sea oil. William Rees-Mogg, the paper’s editor, likened the beleaguered Times to “a man at the end of a windswept pier in some cold and out-of-season resort.” Tim Austin, its long-serving style guru, voiced despair in more prosaic terms: “You didn’t know if the paper was going to come out at night. You would work for it for ten hours and then [the unions] would pull the plug and you had wasted ten hours of your life.”

To his last breath, Roy Thomson implored Denis Hamilton to introduce modern typesetting, already operating across his American stable. The proprietor, comically frugal in his own life, lavish with his cherished papers (“Spend what you want, Denis, but never tell me the amount!”) died in 1976, ownership passing to his less engaged son, Kenneth. After two more years of attrition, a frazzled TNL board stopped the presses in hope of forcing a quick agreement to introduce new technology in phases, along with pay and staff reforms. Instead, most TNL workers took jobs at the papers’ rivals, who eagerly boosted output to draw homeless readers.

The Gray’s Inn Road hiatus lasted through most of 1979, that hinge year, a mammoth £40 million loss, and a silo of resentments primed to burst. And all for nothing: when the presses again rolled, war instantly resumed. In 1980, the journalists — who had been paid through the lockdown — joined the fray, striking for a second big increase in months. For Hamilton, “it was the last straw. Without the journalists’ loyalty we had nothing left to fight for.” Kenneth, the new Lord Thomson, tired of the hassle, put the group on the market.

While the Sunday Times was still a going concern, the Times faced the abyss, as Rees-Mogg’s leader (“How to Kill a Newspaper”) had grasped on their restart. A disentangling of ownership would doom the establishment flagship; a joint purchase might see it unloaded anyway after a decent interval. Any new proprietor needed tools to deal with that implacable iceberg. The papers were back on the streets, at the behest of the chapels. This time, the party really was over.

The seachange

It took until March 1981 for Rupert Murdoch to clinch the title deeds to Thomson House. His News International Ltd, the British arm of his group, was the last viable bid once Lord Rothermere’s Mail stable, which coveted only the Sunday Times, was discounted, and Evans’s fundraising for a buyout of his paper by management, senior editors and advisers had got nowhere (those damned beancounters). “Harold Evans, though he made a great show of leading a cavalry charge intent on buying out the owners, soon threw his hat in with Murdoch’s camp,” recalled Hamilton, while Linklater said Evans was “open to the charge of bad faith [as he] switched sides.”

It was an endorsement Evans spent the rest of his days wriggling away from. In January, following their first conversation, he had described Murdoch as “robust and refreshing. I liked him hugely. There is no doubt he loves newspapers,” and — having consulted staff who he said were of similar mind — confirmed his “preference” in a private note to the Thomson executive Gordon Brunton (“between Murdoch and Rothermere I myself would choose Murdoch for a variety of reasons [though as you know I believe systematic safeguards are required]”).

Harry, like most of those involved, had come to believe that News International was the least worst outcome in business terms. But the deal’s mesh of personality, politics and law made it an enduring source of dispute. It had been smoothed by Murdoch’s courting of Margaret Thatcher, prime minister since May 1979 (when Harry was among a chunk of London’s liberal-left dignitaries to vote for her), and by her trade minister John Biffen’s non-referral of the Murdoch company’s bid to an oversight commission that might have barred it on grounds of excessive market share. These episodes were later invested with ever more tortuous conspiratorial significance, Harry still swinging the lead pitchfork long after the crowd had melted away.

The larger truth is that there were no good options. TNL’s woeful stalemate crystallised that of British society in the period. In each case, years of dislocation were unavoidable, though its precise form was full of contingencies. In the shorter term, the Times could well have gone under without a quick resolution. For his part, Evans ever regretted accepting Murdoch’s invite to edit it (“my ambition got the better of my judgement”) and leaving the Sunday Times (“my power-base as a defender of press freedom”). But had he stayed, it would be under a more vigilant owner and exacting financial regimen. For things to stay the same in his fiefdom, they were bound to change.

In the event, he did go over to the Times, clutching Murdoch’s non-interference guarantees, which were to prove worthless once Rupert’s henchmen Richard Searby and managing editor Gerald Long started turning the screws. The editorial floor was uneasy too. Did Harry metamorphose in the crossing? Not at all, he was ever his ebullient self. This hardened the disfavour of senior Times staff, who (the newspaper’s official historian wrote), “looked upon Evans and the smart and cocky journalists he brought with him from the Sunday Times as aliens from the planet Lower Class. The foot soldiers too went into shock. Here was an editor who rewrote their copy and their headlines, redesigned pages and didn’t go home until he had conducted a post-mortem of the day’s work.”

Yes, good old Harry. One who saw it coming was Denis Hamilton, who added to this litany the editor’s “taking over the duties of his leader-writers, leaving them unemployed” and “constantly (as he had done with me) overspending, or temporarily disguising expenditure.” Hamilton, who as TNL’s chair was key in endorsing Murdoch (“not a perfect purchaser” but “the best available”), had warned him against the choice of “my own protégé from the Sunday Times” (an equally rare note): “I told Murdoch it would turn out disastrously, and it did.” Evans’s appointment was “Murdoch’s fault, from start to finish, a great error of proprietorial judgment,” and not the only one, for he “was a poor picker of men.” In deprecating Evans’s and now Murdoch’s calibre as recruiters, Hamilton does not reflect on his own; but the undertow of regret over Evans in his memoirs (not Murdoch, it was far too late in the day for that) is tangible if unadmitted.

Evans’s tenure began in March 1981 amid a morass on the home front that offered news riches: Thatcher vulnerable, an economy sunk in recession, urban riots, IRA hunger strikes, Labour’s Bennite left on the up, a breakaway to the party’s right, much talk of political “realignment.” For six months, he wrote of the company’s new boss, “Murdoch was an electric presence, vivid and amusing, direct and fast in his decisions, and a good ally against the old guard… I did find his buccaneering, can-do style very refreshing.” Soon those same qualities ended the romance, hitched as they were to overt editorial interference in the paper’s coverage of Mrs Thatcher’s economic travails.

Without Murdoch’s support Harry was exposed, even more so as he lacked aides with a reliable political compass. At the Sunday Times, olympian political editor Hugo Young had been Harry’s lodestar. A belated bid to entice Hugo to the Times culminated on 2 March 1982 with a desperate memo in third-person style, filed in Young’s outstanding archive: “his editor would be utterly committed to him,” vowed Harry, even suggesting Hugo might “be well placed as an insider to succeed to the chair.” The pleading bullishness was all too forlorn, as was soon confirmed by Young’s diplomatic reply (“I feel I can pursue my journalistic interests, and help maintain our shared interests, here for the moment,” was its gist), the last clause presaging his move to the Guardian in 1984 when Murdoch denied him the Sunday Times editorship.

The fin de siècle air of this bleak exchange was appropriate: a week later, Murdoch told Evans to step down, which he did after six histrionic days. An always unwise and often strained cohabitation — both men having arrived at the Times as brash interlopers with differing ambitions — had met its foretold end, leaving rival accounts to pick over the carcass for decades. In this context, Andrew Knight’s coda to the Times’s own obituary of Evans is apt. Knight, a long-term News International affiliate and chair of Times Newspapers since 2012, recalls that Harry’s early choice of Bernard Donoughue as leader-writer and “opinion guru” introduced a “personality ingredient” that “signalled to me his likely demise at the Times.”

Knight observes that the “undogmatically centrist” Harry’s “lack of nous” in hiring Donoughue — who had advised Labour prime minister James Callaghan before working for Knight at the Economist — “caused loss of sympathy inside the paper” and “gave extra ammunition” to a Times staff “who did not enjoy Harry the way his tight-knit Sunday legion had done.” It still surprises, he writes, that Harry, “though a man of action and warmth rather than strong politics, did not divine the likely office politics of his new daily newspaper when it played so effectively to Murdoch’s ‘clear-water’ world view. Murdoch’s was a post-Seventies view already in course of being borne out by events. I was not there but I suspect it was not was not a hard decision, knowing the staff turmoil on The Times, for the independent national directors of Times Newspapers to agree to replace Harry with [his deputy] Charles Douglas-Home.”

In principle, Donoughue was well placed to grasp the politics of his own arrival at Gray’s Inn Road, for he had noted (and in doing so would make famous) a quiet, back-seat remark made by the avuncular Callaghan during the 1979 election campaign. Bernard had said that “with a little luck, and a few policy initiatives here and there, we [Labour] might just squeeze through.” The PM replied: “I should not be too sure. You know there are times, perhaps once every thirty years, when there is a sea-change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or what you do. There is a shift in what the public wants and what it approves of. I suspect there is now a sea-change and it is for Mrs Thatcher.”

Callaghan’s intuition proved sound, though a bodyguard of auxiliaries would be needed to bend history in the right direction. Murdoch’s rout of the print unions in 1985–86, enabling the newspaper industry’s makeover, added oil. By that mid decade, the world of Harry Evans in his pomp on the Gray’s Inn Road was becoming as remote as the Ashton-under-Lyne Weekly Reporter. But a casualty of progress, a music-hall remnant in the film-star age? Far from it. With trademark élan, Harry reached the other side having pulled off a rare midlife combo: Atlantic crossing, new career footing, revamped private life. If that too would link Murdoch and Evans, deeper still was the reciprocity of their casting: menacing dark versus radiant light, with nothing in between.

The second life

This second life had a long gestation. Donoughue’s diary on 27 October 1976, in the midst of a British financial crisis, records: “I went to see Harry Evans in the flat of his lovely new girlfriend — Tina Brown. He told me that the Sunday Times had got its story that the IMF would insist on a sterling parity at $1.50 from Washington… Harry is still angling for the Director Generalship of the BBC.” The two men were players at the game of power: Donoughue had ambitions of his own to run the Bank of England. But over the private life of “one of my closest friends,” he was well behind the curve.

Tina, at twenty-two, was a kinetic Oxford graduate whose pen, vim and allure had by then felled an eclectic swathe of London’s male glitterati. It was three years since Harry, given Tina’s New Statesman clippings by the agent Pat Kavanagh, had asked Sunday Times features editor Ian Jack to commission her, sponsored her stay as a New York freelance, and lined up a staff contract (blocked by the journalists’ union chapel as Tina hadn’t served time on a local paper, to Harry’s fury at Jack’s expense). From late 1974, wrote Harry, “[we] corresponded about her work, and then about newspapers and literature and life, and so our relationship began. I fell in love by post.” Private Eye, already taunting Harry’s new motor-bike-and-black-leather look, was soon noting events where “[the] Dame was accompanied by his beautiful and talented young discovery Tina Brown.”

Enid Evans, wife of Harry for twenty-five years until their 1978 divorce, and mother of their three children, continued to teach, work as a magistrate, and support educational initiatives in the family’s Highgate, north London home patch until her death in 2013. “We preserved an affectionate friendship that has endured to this day,” wrote Harry in 2009, describing their union as “serene.” (Harry’s gestures at self-inquiry work to deflect it: “I told myself it was a typical mid-life crisis”; “Hamilton was a master delegator. I was a meddler. He was reticent. I wasn’t.”)

Harry and Tina married in August 1981 at the East Hampton, Long Island retreat of the Washington Post’s Ben Bradlee, who had “made a second marriage with his paper’s intrepid and glamorous young Style writer, Sally Quinn.” (In fact a third.) “After champagne and cake, we drove into Manhattan for a honeymoon, all of one night at the Algonquin.” Work called: Tina back to London as editor of the high-society Tatler, Harry “to meet Henry Kissinger at the Rockefeller family estate in the Pocantino hills of New York State where I was editing a second volume of his White House years.”

The event stands as a fitting entrée to luxuriant decades of professional and social whirl, the British duo’s super-networked celebrity at once status marker and career enhancer. While Tina edited Vanity Fair (1984–92), the New Yorker (1992–98) and the Daily Beast (2008–13), in between blowing upwards of $50 million on her Miramax-funded Talk magazine (1999–2002), Harry spent a protracted New York apprenticeship editing US News & World Report, perennial third to Time and Newsweek, then a sleek travel monthly with an ethical tinge (“The Harry Evans called back and said: Malcolm Forbes and some other billionaires are taking their yachts up the Amazon. Would you be interested in covering that for our first issue?”) before reaching the big league in 1990 as editorial director of Random House, where over seven years his penchant for star names, vast advances and hyperactive marketing swelled then near burst his own repute.

Through a frenetic period, Tina and Harry gained extra cachet as A-list, paparazzi-buzzed Manhattan party hosts to grandee celebrities (think Bill Clinton, Nora Ephron, Bianca Jagger, Henry Kissinger, Madonna, Salman Rushdie, Simon Schama), each gathering signalled by their triplex apartment’s furniture being consigned to a giant truck which would trundle around Manhattan for the duration. A book might be its pretext, the author its prime guest, “social butterfly” Harry doing a turn at the microphone — which, as Jacob Bernstein says in a neat portrait of these vanished times, “Mr Evans did not have to be an expert on a subject to monopolise.”

The apogee of their power coupledom, and perhaps of a brief age of liberal swank tout court, lay in Harry’s fundraising for Tony Blair before the 1997 election, when New Labour’s made men would fly in to parley with wealthy influencers such as investment banker and New York Review of Books contributor Felix Rohatyn. The journalist and Clinton ally Sidney Blumenthal hosted a Washington party where Tony’s speech had its obligatory self-deprecating jest, his “I remember Tina well. We went to Oxford together. She gave the most fabulous parties to which she never invited me” the cue for Tina to complete the double act with “We’ll soon put that right!”

Such jaunty mateship provoked transatlantic chatter that Tina or Harry might take a big job in a Blair administration: envoy in Washington for her, arts minister for him? In turn, their London media slots, charity hooplas, or honours (Brown’s CBE in 2000, Evans’s knighthood in 2004) gave plugged-in locals a vicarious taste of their Manhattan aura. But distance mainly kept apart the two segments of the Tina-and-Harry show and of their individual careers. In London, Harry was journalism’s departed knight, the local head boy made vaguely good across the pond; in New York, he was Tina’s consort — dubbed “Mr Harold Brown” by the gossip queen Liz Smith — then, via an opportune vault, her co-star. The prescribed terms had no room for seeing Harry’s story as one, noting its recurrences, or considering that his American trajectory might cast retrospective light on his British one.

Most snippets that did reach London matched the frame, as when Evans’s sponsoring of disgraced Clinton aide Dick Morris’s memoir unleashed a “wave of indignation” in New York; so “shaken” was he by the furore, reported the Independent’s John Carlin, that “were [Evans] to receive a flattering offer back in Britain, he might be tempted to return. After all, back home he is regarded by his peers as a rock of journalistic integrity. In America, whose culture he has manifestly understood but cannot wholeheartedly embrace, he has come to be regarded as an unprincipled opportunist — in much the same way, in other words, that he regards his nemesis, Rupert Murdoch.”

The souring mood led to investigative auditing of strains in the couple’s media dominion. Suzanna Andrews’s “The Trouble with Harry,” a formidable New York magazine cover profile in July 1997, sparked by the “amalgam of theatrics, money and controversy” that Evans had “gleefully detonated” in promoting Morris’s work, went on to track how “the marketing champ of the book business,” noted for his “eager courting of the famous and powerful,” had become “the poster boy for the publishing crisis.” A Random House shuffle that raised Ann Godoff to editor-in-chief and marginalised Evans, plus evidence of colleagues’ dislike of his way of operating (variously “cynical,” “tasteless,” “downmarket and shameless”), gave the investigation further topicality.

Evans was moved to a top-floor office — piquantly, days after Blair entered Downing Street — for what became a six-month sojourn before his departure. In an echo of his unhappy Times finale, the backdrop to Harry’s ousting from the Random House frontline was a divided staff. Again, most insiders were relieved. Robert Kolker’s “Waiting for Godoff,” published in March 2001, quoted one that “Evans’s event-planning department came from Hollywood, and his mammoth book advances sometimes seemed to come from there too,” while a “long-established star” said of Godoff: “Harry thought he was a character playing a publisher. She’s the real deal.” Marlon Brando (a $5 million advance on another fiasco) was out; Arundhati Roy, Susan Orlean and Zadie Smith in. Ruth Reichl, food writer and memoirist, describing Godoff as “probably the anti-Harry,” illustrated the point by distinguishing “people who constantly try to remind you of how important they are, and people who constantly try to make you forget it.”

Another sign that New Yorkers were cooling on the Tina–Harry show was a book-length dissection of the hot couple’s Manhattan years. Judy Bachrach’s Tina and Harry Come to America, an acrid if thorough account of the couple’s “uses of power” in the city’s circuits of wealth, glamour and literary commerce, proved ill-starred in its release date, July 2001, and its racy tone. Yet Bachrach’s argument, and Andrews provides more discreet back-up in Evans’s case, has a kernel: that Tina–Harry’s forte was to be the advance guard in American upper-end publishing’s move from seriousness (if also sluggishness) to vaudeville.

The patronage of two moguls was central to the couple’s ascendancy: S.I. Newhouse Jr. (owner of Condé Nast, the New Yorker from 1985, and Random House 1980–98), Mort Zuckerman (owner of US News and World Report and several papers, plus Atlantic Monthly Press 1980–99). A third, broadcasting magnate Barry Diller, was a key Tina patron. An ad hoc part of the deal was Si and Mort’s resort to expediency in handling their charges. When Harry was catapulted to Random House, the “whole editorial wing — Bob Loomis, Jason Epstein — was against him,” and staff were “openly defiant,” an editor there told Suzanna Andrews. “Everybody was sure that Harry had gotten the job because Si wanted to keep Tina happy.”

But Si, “the Howard Hughes of the media world,” in Nicholas Latimer’s term, and Mort, the mercurial real-estate tycoon and “ultimate parvenu,” also godparent to one of the couple’s two children, found Tina and Harry equally adept in the uses of expediency, which in their case lay on a spectrum from tawdry via crafty to creepy. At the former end was a light pre-publication mugging of William Shawcross’s Evans-sceptical biography of Murdoch, carried in Tina’s second issue of the New Yorker, which sparked the wrath of Shawcross’s friend, novelist John Le Carré.

The pincer at work on the New Yorker’s Daniel Menaker struck him on the way to meet Harry following an out-of-the-blue call, as described in his wry memoir The Mistake. “Where are you going at this time of day?,” a colleague asked. “‘To see Harry Evans,’ I say. ‘Oh, no!’ she says. And at this point, with a cold, sick feeling, I realise what’s going on: Tina now wants me out of the magazine and has persuaded her husband to offer me a job.”

Menaker would flourish as a book editor, starting with Primary Colors (his title too). But still. “In work,” Harry wrote in My Paper Chase, “Tina and I remained the mutual support team we’d always been in editing and writing at all levels.” This opus, par for the course, had no mention of Menaker, nor of Dick Morris, nor Wyndham or McCooey, nor Wesker, to name just these. Donoghue pops up once, unavoidably, for his diary is quoted: a cabinet minister is daunted by Harry’s “granite” toughness on open government. Mort Zuckerman, a mainstay for fifteen years — one of those “capricious billionaires” to whom Evans was a “courtier,” wrote media analyst Michael Wolff — gets two condescending references (“I told my boss Zuckerman he’d completed his apprenticeship as an owner in record time,” goes one).

The creepiness quotient soared when Harry’s $2.5 million advance for Morris’s dud provoked the New York Times’s Maureen Dowd to imagine Evans entreating J.D. Salinger (“Look, Jerry, fiction is in big trouble. This is the age of the memoir. I got Colin [Powell] $6 million. I got Dick $2.5 million, I got Christopher Reeve $3 million… I’m an expensive hustler… Join the party, Jerry… Tina will serialise it”). Brown’s New Yorker — whose advertisers she had hosted at an event promoting Morris’s book, with the author as star guest — got further into the mire by disparaging Dowd in its pages, again without mention of its editor’s interest. Evans, in his often brittle interview with Andrews, referred to Dowd as “that silly woman in Washington.”

Evans’s gaucherie towards some women, hinted at in Andrews’s coy reference to his “famously flirtatious manner,” is pursued with relish in Judy Bachrach’s book. Elsewhere, a Manchester pal and later Sunday Times colleague, Peter Dunn, says that “in truth, there was always a puppyish innocence to [Harry’s] games.” That aside, his intolerance of criticism — or even alarm at its prospect — could go much farther than being “magnificently aggrieved” (Andrews again) when interviewers proved other than fawning. Evans sent frequent hassling letters to Bachrach and her publishers as she researched her work, then used Britain’s litigant-friendly defamation laws to thwart its release in the country. Bachrach says she was “bent out of shape” by Evans’s sheaf of “ominous” preemptive complaints, including an enigmatic warning that the author “would see [the couple’s] whitened bones as you walk through the desert.”

Tina and Harry’s brazenness was a motif of their two New York decades of “ghastly chic” (Dunn’s label, in a New Statesman review of Bachrach’s proscribed book, dated 10 September 2001). Harry’s writs blitz on Private Eye continued, securing one win, Donoughue on that occasion his joint plaintiff. “There is something to be said for British libel law because it encourages better journalism,” he would say as he went on to intimidate the gadfly Toby Young, then half Evans’s seventy years, whose latest piece had teased that Evans, given a post-Random House berth by Mort Zuckerman at the tabloid New York Daily News (to its staff’s dismay), might be running out of friends. Evans — who had the nerve to tag Young a “journalistic stalker” — demanded via London’s courts an apology, legal fees, damages and that he “desist forthwith from further defaming, denigrating and ridiculing Mr Evans and his wife.”

Evans would then upset even Mort, to whom he was “the decathlon champion of print,” by gratuitously puffing Tina’s buzzy new venture, Talk, on the Daily News’s front page. In the wake of Talk’s hyped-to-the-Miramax launch party at the Statue of Liberty, costing half a million dollars — “a decadent fin-de-siècle bash for Hollywood stars, supermodels and assorted cultural and business titans” — it now had Harry’s “outer-borough, lean and mean tabloid machine” rooting for it.

There is enough material here for an entire conference, as the psychiatrist says in Fawlty Towers. The point is underlined when Bernard (now Lord) Donoughue’s diaries — at their worst a cloying inventory of Labour and establishment cronyism across five decades — reach May 1996, twenty years on from that night at Tina’s, and a lunch with Harry at the Garrick club:

“Harry was in great form. We discussed all our past deeds and misdeeds. He was delighted I had defeated Murdoch on the Broadcasting Bill, sharing the sense of revenge for Murdoch’s appalling treatment of us on the Times. We both agreed we made a mistake in 1982 in not joining Melvyn Bragg in taking over Tyne-Tees television. We would all now be multimillionaires (Melvyn is anyway)… He and his wife Tina Brown have done very well in America, an astonishing success story… Today he still refers to lovely Enid as ‘the wife’ and Tina as Tina. Nobody can help loving Harry and he gets forgiven for everything. At lunch we discussed friendship and loyalty. He said there are no true friends in New York… once you have failed at something no one wants to know you. Drinks in the evening with Melvyn Bragg, another true friend. He is very keen to take over the Arts Council when we’re in government.”

The Murdoch motor