On the evidence, Sussan Ley seriously lacks political judgment. Still recovering from her declaration five weeks ago that a Coalition government would repeal the government’s rejigged Stage 3 tax cuts — a clunker that would have lumbered the opposition with a massive, complicated target all the way to election — on Thursday afternoon the deputy Liberal leader posted an odious message on the site formerly known as Twitter.

If you live in Frankston and you’ve got a problem with Victorian women being assaulted by foreign criminals, vote against Labor.

If you do not want to see Australian women being assaulted by foreign criminals, vote against Labor.

Send Labor a message.

— Sussan Ley (@sussanley) February 29, 2024

Having happened to watch question time that day, I can attest that she (or her staffer) was fully on song with the opposition’s chief theme: that Melburnian women should be terrified of being assaulted by convicted sex offenders — foreign (ie. dark-skinned) ones to boot — released into the community by the Albanese government.

It’s a very Peter Duttonesque message, but he and his team usually deliver it with more subtlety — it sticks better if recipients have to join a few dots — and, crucially, with deniability. By blundering in with the quiet bits out loud, Ley made it more obvious, if not necessarily more objectionable.

It’s all part of the Dunkley frenzy, of course. As with all federal by-elections seen as contestable between the major parties, this one, caused by the death of Labor MP Peta Murphy, has gone from being cast as a useful indicator of how the parties are “travelling” to something incredibly important in its own right: massive tests for the prime minister and opposition leader.

Whenever I write about a by-election I devote some words to explaining why these events are useless predictors of anything and why they only matter because the political bubble believes they do. Readers familiar with these observations can skip the next few pars.

There are two main reasons. The first is that the sample, while huge, is neither random nor scientifically weighted. It’s just one electorate. At the 2022 general election a national 3.7 percentage point swing comprised a spread of 151 seat swings, from 14.2 points to Labor in Pearce (Western Australia) to 7.2 points to the Liberals in Calwell (Victoria). (The 8.3 points to the Lib in Fowler (New South Wales) was bigger, but that was an independent–Labor contest and the two-party-preferred figure comes from an Electoral Commission recount for purely academic purposes.)

So even at a general election, one seat’s swing will rarely approximate the national one.

But perhaps more importantly, by-elections (except in the rarest of cases) are not about who will form government. It’s true that a proportion of the electorate — probably still a majority, but a shrinking one — will always vote for a particular major party out of loyalty, but for the rest the triviality of the contest liberates them to act on other impulses. “Sending a message” is tried and tested (see tweet above).

Candidates also make more of a difference at by-elections. So might the weather. Low turnout is a feature of this genre, worth potentially a couple of percentage points one way or the other.

Still, by-elections do end up being important, precisely because the political class believes they are. They can influence the future, particularly leaders’ job security, but only because of how they’re interpreted. (Would we have ever seen a Bob Hawke prime ministership if Liberal Phillip Lynch had not resigned in Flinders in 1982?)

The magic number here is the margin: 6.27233 per cent to be precise. A swing to the opposition above that figure would shake parliament’s walls, generate shock and awe in the press gallery and even, perhaps, send Labor’s leadership hares out for a trot. After the Voice “debacle,” Anthony Albanese fails another electoral test!

A swing to the government would similarly damage Peter Dutton, rendering his chances of surviving until the next election worse than they are now. And anything in between will be energetically spun by both sides and their media cheersquads.

So what can we say about Dunkley? Antony Green’s page is up, and I’ve followed his lead when calculating average swings by restricting the time period to 1983 onwards. But I’ve also excluded by-elections caused by section 44 of the Constitution — of which we had a slew around six years ago — because in all of them (or at least those with identifiable with two-party-preferred swings) the disqualified MPs ran again. These deserve their own category given that the absence of the personal votes of sitting MPs is the big driver of the difference between swings in opposition-held seats and government-held seats.

That leaves twenty-three by-elections in the past forty-one years with two-party-preferred swings. In the ten opposition-held seats (including Aston and the low-profile Fadden last year) the average swing was an almost negligible 0.8 points to the opposition.

Those caused by resignations by government MPs (eleven in total, the most recent in Groom in 2020) average to a much bigger number, 7.6 points to the opposition. And when they’re brought on by the death of a government MP — it’s a tiny sample of two (Aston 2001 and Canning 2015) — the swing is 5.5 points to the opposition. If we include that pair with the resignations we get 7.2 points to the opposition from thirteen events.

(There were no opposition by-elections caused by death with two-party-preferred swings in that period.)

So you might want to use that 5.5, which would see Labor retain the seat, or 7.2, which wouldn’t. Or you could slot in any other number, because another feature of by-elections is that they’re unpredictable.

The graph below shows Labor two-party-preferred votes in Dunkley since 1984. To adjust for redistributions, notional swings are subtracted from results going backwards. The blue dots show the actual vote at each election; the fact that so many are below the orange line reflects a 2018 redistribution that favoured Labor by an estimated (by the AEC) 2.5 points after preferences.

The big gap between the orange and red lines from 1998 to 2013 (particularly from 2001) is largely because of the big personal vote built up by the energetic Liberal Bruce Billson, first elected in 1996. He ended up in Tony Abbott’s shadow cabinet and then in cabinet; he was subsequently dropped by new prime minister Malcolm Turnbull in 2015 and retired at the 2016 election. See the dramatic narrowing between red and orange at that election with the absence of his name on the ballot.

Dunkley was retained by the Liberals’ Chris Crewther, but the aforementioned redistribution saw the electorate going into the 2019 poll as notionally Labor. In that year Victoria was the only state to swing to the opposition, and Murphy (who had also contested in 2016) took Dunkley (or retained it vis-à-vis its notional position) with a swing slightly above the state average. If Crewther generated a sophomore surge in that single term, it was counteracted by other factors, perhaps including the Labor candidate and campaign. Murphy seems to have enjoyed a surge in 2022, registering a swing well above the state average. Which takes us to where we are now, and that margin of 6.3 points.

Note that the orange line is above 50 per cent in 1998, 2010 and 2016. All else being equal, this suggests Labor would have won on the current boundaries in those years. All else ain’t equal, and the assumption gets more questionable the further back we go because of demographic changes and compounding errors in those post-redistribution estimates of notional margins. (Notional margins are rather hit and miss. For one thing they can’t take into account postal votes; for another they ignore personal votes in booths from neighbouring electorates.)

But it is reasonable to believe that Dunkley, as it is defined today, would probably have been won by Labor in 2010 and 2016. So although Dunkley was long held by the Liberal Party it’s not really accurate to call it a natural Liberal seat.

Other factors?

Federal electorates tend to be pulled by state tides. One element is the standing of those second-tier governments, and while Victoria’s Labor government under new premier Jacinta Allan is still ahead in opinion polls, the leads are more modest than under Dan Andrews. Put less clinically, Andrews was an accomplished communicator, including on behalf his federal counterparts, and he is gone.

Working the other way, Victorian Liberal leader John Pesutto still seems as pitiably bogged down by his party’s right wing as he was eleven months ago during Aston.

Then there’s the personal vote. On the evidence, which isn’t substantial, Murphy had a good one. (The bigger her personal vote, the worse for Labor’s chances on 2 March.)

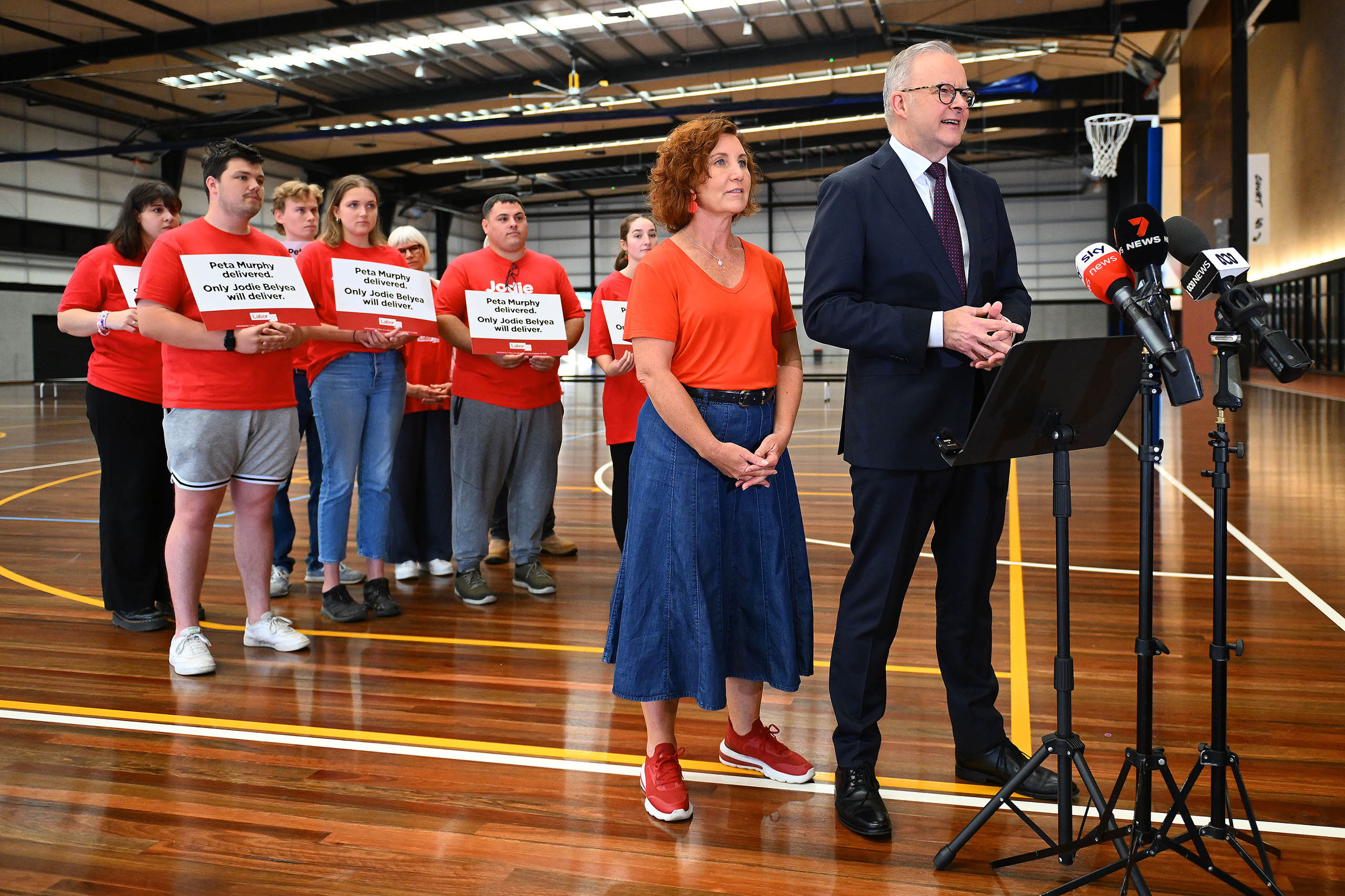

The Liberal candidate is the Frankston mayor Nathan Conroy, who should bring a ready-made personal vote in parts of the electorate. Labor’s Jodie Belyea has long been involved in the local community but from reports lacks his profile. As noted above, attitudes to candidates can matter a lot at by-elections.

Conroy drew the top ballot spot and Belyea the bottom. That’s got to be worth a point or two for the Liberal overall.

Dutton is reported to be spinning “that a swing of between 3 per cent and 5 per cent would be a respectable outcome,” which suggests his party is expecting something bigger. YouGov, with a small sample, puts the Liberals on 51 per cent after preferences (about a 7 point swing). Polling before by-elections, including surveys conducted by the parties, is notoriously rubbery.

Anything can happen at by-elections, but if forced to choose I would tip a Liberal victory. If that does eventuate, the media frenzy about Labor’s leadership, including whispers from unnamed party sources, will not be for the faint-hearted.

December’s “one-term government” sightings will certainly make a comeback. •

Further reading, in alphabetical order

• ABC’s aforementioned Antony Green

• Kevin Bonham

• Pollbludger (William Bowe)

• Tallyroom (Ben Raue)