When Shinzo Abe suddenly announced his resignation as Japan’s prime minister, on health grounds, late last month, Scott Morrison was instant in his praise. “Shinzo Abe is a true friend. He is Australia’s true friend,” the prime minister said, describing Japan as “one of Australia’s closest partners, propelled by Prime Minister Abe’s personal leadership and vision, including elevating the relationship to new heights under our Special Strategic Partnership.”

Just two weeks earlier, though, a proposal by Japan to take the strategic partnership to even greater heights, ranking that country with Australia’s longstanding anglophone allies, had met with a resounding silence in Canberra.

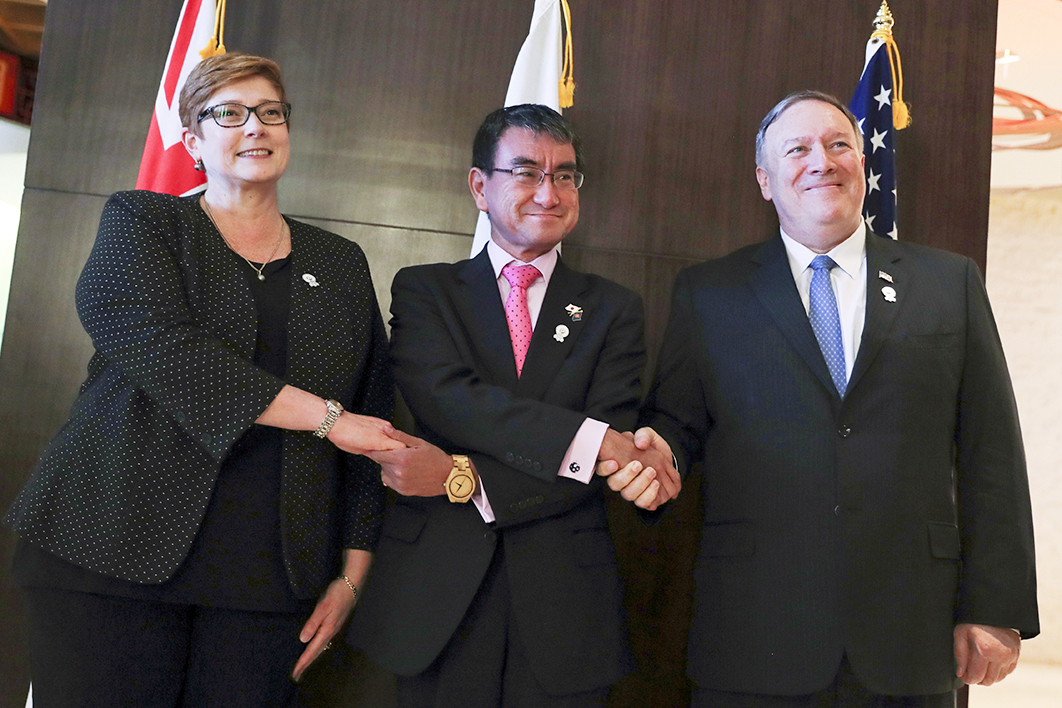

In an interview with Nihon Keizai Shimbun on 14 August, defence minister Taro Kono said that Japan was keen to expand its cooperation with the “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing pact that links the United States, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. “These countries share the same values,” he told the newspaper. “Japan can get closer [to the alliance], even to the extent of it being called the ‘Six Eyes.’”

Japan has been approached about sharing its information “on various occasions,” said Kono. “If approaches are made on a constant basis, then it may be called the ‘Six Eyes.’” The country need not go through formal procedures to join officially, he added. “We will just bring our chair to their table and tell them to count us in.”

The Five Eyes pact, created in 1946 with just two full members, Britain and the United States, grew out of collaborative efforts to collect and break the coded signals of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Australia had been involved in code-breaking against Japan since the 1930s, first with the British in Hong Kong and then with the Americans and other allies in Melbourne and Brisbane. Along with Canada and New Zealand, it was elevated from associated status around 1955 after upgrading domestic security.

The achievement of the wartime Allies in breaking enemy codes was kept secret for nearly three decades after the war, partly because the same capabilities were being deployed against the Soviet Union and other powers. It was blown open by the publication in 1974 of a book called The Ultra Secret by a former staffer at Britain’s now-famous Bletchley Park. Thanks to their “Cambridge” spy ring, though, the Soviets had long known about the code-breaking.

Japan has a highly developed signals intelligence capability and for decades has been a valued contributor in exchanges with the Five Eyes group. It listened to Chinese tank commanders preparing to enter Vietnam in 1979 during Deng Xiaoping’s “punishment” for its invasion of Cambodia. It heard the chatter of Soviet fighter pilots in the shooting down of the Korean Airlines Boeing 747 in 1983. In 2018, its agencies joined those from the Five Eyes in a US war game simulating a hostile attack on the allies’ satellite systems. It closely tracks Chinese and North Korean manoeuvres.

But Kono has not so far been rushed with invitations to the alliance top table. Although Japan clearly wants to move ahead of other powers sharing information with the Five Eyes — including France, Germany, South Korea, Norway and Denmark — even the most fervid Western supporters of bringing Japan out of its post-1945 diffidence about defence and security concede it will be some time before that particular set of eyes is a regular at the table.

No one is blackballing Japan’s membership of the club, it seems, but as yet no proposer or seconder has emerged.

Asked to comment on Taro Kono’s remarks, Australia’s defence department says that Australia values its “close and enduring partnership with Japan, including our strong defence cooperation” and points to the joint statement of a Five Eyes defence ministers’ meeting on 23 June, which “recognised the role of regional partners and institutions in shaping globally and across the Indo-Pacific a stable and secure, economically resilient community, where the sovereign rights of all states are respected.” Apart from that, “consistent with longstanding practice, government does not comment on intelligence matters.”

The chair of the Australian parliament’s joint committee on intelligence and security, Liberal Party MP Andrew Hastie, did not respond to a request for comment.

The warmest endorsement for closer Japanese involvement has come from the Conservative chairman of the British parliament’s foreign affairs select committee, Tom Tugendhat, after a visit from Kono in July. “We should look at partners we can trust to deepen our alliances,” he said. “Japan is an important strategic partner for many reasons and we should be looking at every opportunity to cooperate more closely.”

Washington is not pushing the pace. “The Japanese are definitely keen,” acknowledges Michael Green, a senior Asian affairs specialist in the George W. Bush administration’s National Security Council who is now at Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, or CSIS. “Full ‘Five Eyes’ is not on the cards,” he adds, “but there is support for an à la carte role for Japan.”

The most obvious inhibition is cited by another US specialist on Northeast Asian strategic affairs, Brad Glosserman, now at Tama University in Tokyo and previously at the CSIS offshoot in Hawaii, Pacific Forum. Japan’s partners recognised the value of its intelligence product, he writes, but worried about the security of information they gave Tokyo. Laws to protect official secrets passed by Abe’s government in 2013 have not completely allayed those concerns.

“The Japanese leak like a sieve and the idea of the secrecy laws is all about trying to plug those leaks or make it more difficult to leak,” adds a former senior Australian official closely involved with Japan. “If they were ever going to have access to high-level information they needed to assure the US and other Five Eyes partners they weren’t going to read it on the front page of the Nikkei the next day.”

Rory Medcalf, head of the National Security College at the Australian National University, agrees that more work is needed. “It is widely believed that Japan does not yet have the system of security clearances and standards of information protection that would be required,” he says. “Having said that, there is much that the Five Eyes could do to collaborate with Japan — and with France, the logical seventh eye and the way in to Europe.”

In seeking deeper protection for secrets, not only in military and intelligence affairs but also now in technology, Glosserman says the Five Eyes were up against “cultural obstacles” in the form of the Japanese public’s resistance to government secrecy and “thought control.”

This is certainly true, but it might be added that Abe only added to the fears with his push for great patriotism in school education, his erosion of the independence of the national broadcaster NHK, his attacks on the Asahi Shimbun and other liberal media, and his nostalgic nationalism, all of which stirred collective memories of pre-1945 conditions.

Then there’s the view from inside the clubhouse. “The second obstacle to Japan’s membership is also cultural — but this one exists among the Five Eyes members,” says Glosserman. “The group shares deep historical and cultural ties that stem from a common Anglo-Saxon heritage; they’re all native English speaking too. Seventy years of cooperation has given them a fluency, comfort and confidence that compounds their sense of identity and separation from non-members. All this is subtle and immeasurable, but it is palpable and it matters.”

Not that the Five Eyes partners share everything. During Sukarno’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia in the early 1960s, the late Hunter Wade’s position as New Zealand’s envoy in Singapore gave him a seat in its joint intelligence committee. At a certain point, Wade once told me, the British chairman would cough, and the American representative would leave. At a second cough, the Australian and New Zealand officials would exit.

During the 1999 crisis in East Timor, Canberra’s efforts to keep certain “Australian Eyes Only,” or “Austeo,” material from Washington led to the suicide of defence intelligence liaison officer Mervyn Jenkins, who had been blamed for passing it to the Americans.

But in its original core business of signals intelligence, Five Eyes has the firm rule that each partner must share, without being asked, its entire stream of “raw” material and “end product,” or the assessments made from it. The partners are not to spy on each other’s communications (unless asked), and their human intelligence agencies — the CIA, MI6, ASIS and so on — are not to recruit each other’s nationals without permission. Those are the rules, anyway.

Australia’s intelligence and military links with Japan have tightened greatly over the past two decades. After the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States, the then secretary of Australia’s foreign affairs department, Ashton Calvert, and the US deputy secretary of state, Richard Armitage, started a regular trilateral security dialogue with Japan’s foreign ministry at vice-minister level.

Then, in 2006–07, the Australian army provided protection for Japanese military engineers in Southern Iraq. Prime minister John Howard signed a joint declaration on security cooperation with Abe during the latter’s first short spell as prime minister. As well as increasing intelligence exchange and joint operations to enforce North Korea embargoes, ASIS is reported to have joined MI6 in helping Tokyo set up its own external spy agency on the British model.

“There’s hardly anything we hold back, and they deeply appreciate that,” says Warren Reed, a self-disclosed former ASIS officer and Japanese-speaker once posted in Tokyo, whose latest spy novel, An Elephant on Your Nose, has Japanese and British agents working together against a terrorist plot. “I don’t know whether it is necessary to actually put the cherry on the cake.”

Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party is still deciding on a successor to Abe, but it seems unlikely Taro Kono will get the job and be in a position to push his Five Eyes membership application at a higher level. As a Georgetown University graduate fluent in English, though, the relatively liberal defence minister is well placed to allay cultural reservations on both sides. And, at fifty-seven, he has more years on his side than the two front-runners for PM, Yoshihide Suga and Shigeru Ishiba, both members of the hawkish and retro-nationalist group Nippon Kaigi. His turn may yet come.

Still, if Canberra really wants to show its faith in Japan, it could openly agree to the cherry being put on the cake. •